From: Alexandre Laurin

To: Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland

Date: October 14, 2021

Re: Tracking Capital Gains: Not Just for the Rich

Government deficits, along with distributional concerns, have fueled calls for heavier taxation of capital gains in recent years. Yesterday, we examined modelling around taxpayer responses to any increases.

Today, still working off my article in the latest issue of Perspectives on Tax Law & Policy, we look at who, exactly, is reporting capital gains, and find that these gains are less concentrated in the hands of taxpayers at the top of the income scale than is widely believed.

CRA data are widely used to show that most capital gains accrue to very high-income individuals. The data, however, include capital gains in the income definition used to classify individuals – thus, more than 50 percent of the gains in 2017 were reported by those with annual incomes over $250,000, and more than 80 percent by those with income over $100,000. Although this distribution is factually correct, it is of limited utility for policy purposes because it merely reproduces the very skewed distribution of the underlying annual capital gains themselves.

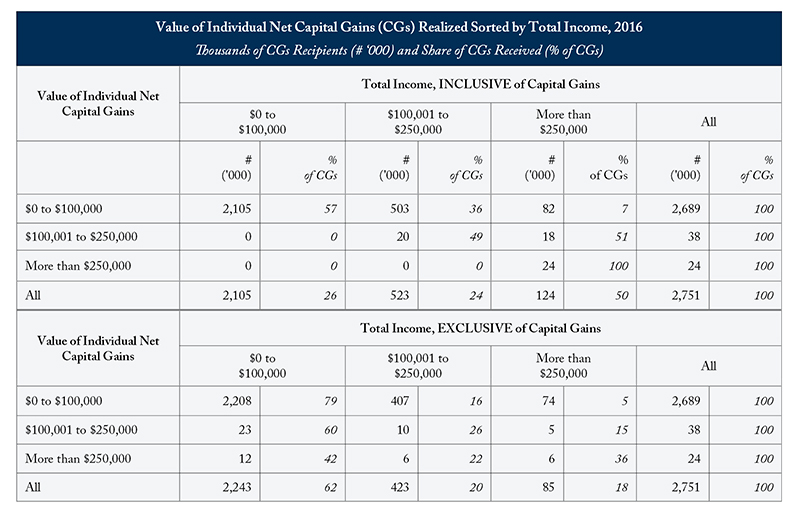

A very few, very large, capital gains account for most of the value of total gains realized in a year. Using Statistics Canada’s Social Policy Simulation Database and Model, I calculate that 39 percent of the total value of all gains were realized by only about 24,000 recipients – 0.9 percent of all recipients – each reporting gains exceeding $250,000. An additional 38,000 recipients – 1.4 percent – reported gains ranging from $100,000 to $250,000, constituting a total of 15 percent of all gains realized. Overall, 2.3 percent of all recipients realized about 54 percent of the value of all gains.

An important policy question emerges: Are these large gains occasional or recurrent? In other words, are these very large gains earned year over year by the same limited number of persons, or are they earned over many years by different individuals realizing a once-in-a-lifetime large gain. Both interpretations lead to different policy implications.

Gordon and Wen find that large capital gains are disproportionally an irregular source of income for recipients. Many transactions giving rise to large capital gains, such as the sale of a rental property held over many years, are occasional in nature. And the fact that the distribution of capital gains is skewed toward few, but very large gains, points to large gains likely being an irregular source of income for at least a substantial proportion of recipients.

Suppose that mostly the same recipients realize very large gains year over year. When we include capital gains in total income used to sort taxpayers, we find:

a) 50 percent of net gains (in value) are realized by taxpayers with total income over $250,000 – 80 percent of which would be regularly realized by the 24,000 individuals with gains also exceeding $250,000; and

b) 74 percent of the gains (in value) are realized by taxpayers with total income over $100,000 – 73 percent of which would be regularly realized by the 62,000 individuals with gains also exceeding $100,000.

Clearly, the skewed distribution of gains drives the lopsided incidence of gains sorted by income, and one would be correct to affirm that changes to capital-gains taxation would mostly affect high-income earners.

Now suppose that large capital gains are an occasional, rare occurrence for most recipients. When we exclude capital gains from the income definition used to sort taxpayers, we find:

a) 18 percent of the gains (in value) are realized by taxpayers with (other) income over $250,000 – only a quarter of which also have capital gains over $250,000, and

b) 62 percent of the gains (in value) are realized by taxpayers with (other) income less than $100,000. One would be correct to affirm that although capital gains are still disproportionally reported by high-income earners, they are much less concentrated at the top than widely believed, and changes to capital gains taxation would affect a great number of middle-income recipients for whom large gains are a rare, perhaps unique, occurrence.

Although the reality sits in between these two extreme interpretations, in my view, it is unlikely that large capital gains constitute a source of steady annual income for most recipients. They are likely a rare occurrence for most.

Equitable tax treatment requires that heavier taxation of capital gains, if implemented, should be accompanied by taxable income averaging provisions. Smoothing the taxation of gains over a number of years would reduce the tax penalty faced by taxpayers bumped into a higher tax bracket for a single year as a result of the one-time realization of large capital gains.

Alexandre Laurin is Director of Research at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.