Federal budgets are an annual rite of spring in Ottawa, as is the deluge of advice to the Department of Finance. But budget-making is a yearlong process, and the work is now in progress. Accordingly, the C.D. Howe Institute is presenting a series of Intelligence Memos in the next few weeks, outlining recommendations that we hope will help inform the policy decisions that are being made now.

From: Grant Bishop

To: The Honourable Bill Morneau, Minister of Finance, and the Honourable Navdeep Bains, Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development

Date: November 6, 2018

Re: Foreign Investment Would Benefit from the End of Net Benefit

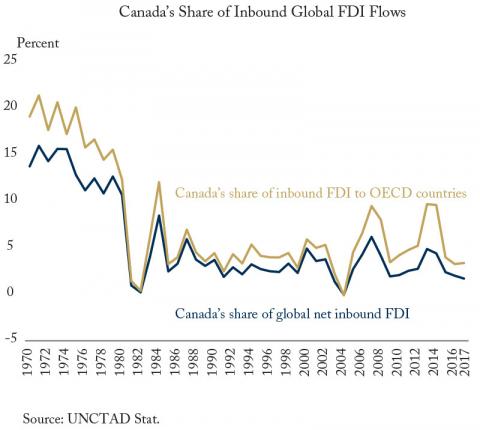

The federal government has recently trumpeted the importance of attracting foreign direct investment to Canada’s economy. The Council on Economic Growth for the Minister of Finance observed that Canada has lagged its developed peers in attracting FDI (see Figure 1). Following its recommendations, Ottawa created a new federal agency, Invest in Canada, committing $218 million over five years in the 2017 budget to formulate a strategy and a “single window” framework for enticing new foreign investors.

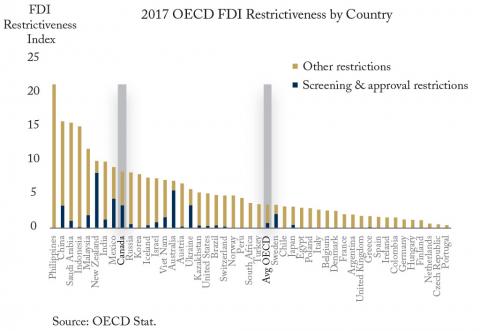

However, Invest in Canada does not address Canada’s main weakness in attracting foreign investment. Canada still ranks as one of the most restrictive destinations in the OECD for foreign investment (see Figure 2). This is largely a product of Canada’s screening process for foreign investments: Large foreign investments are subject to review for “net benefit” and approval by the Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) under the Investment Canada Act (ICA).

The ICA currently requires foreign acquisitions of Canadian assets above certain thresholds to be approved (smaller transactions need only provide notification – though these may require national security clearance). The threshold for review varies depending on whether the foreign investor is from a country that has a trade agreement with Canada or is a state-owned enterprise.

Net benefit review risks deterring productivity-enhancing acquisitions, first as a barrier to entry for foreign firms and also dampening competitive pressures within the Canadian economy. To satisfy the minister of the net benefit to Canada, foreign investors must often provide undertakings of how they will operate the acquired assets. This review is a burden that domestic companies do not face: Canadian companies do not need to prove net benefit of an acquisition to Canada, even though they also restructure production to improve efficiency or move activities offshore to rationalize costs. The net benefit review provides a conduit to extract value from foreign acquirers based on political considerations – with the risk that foreign investors will shy away.

As I argued in an earlier paper, the economic rationale for foreign investment review has always been unclear, and Canada’s review regime runs contrary to the aims of Canadian competition policy. Canada’s foreign investor review was spawned after a surge of economic nationalism and backlash against foreign ownership in the Canadian economy during the early seventies. Although the ICA replaced the Foreign Investment Review Act in 1986, the same factors for assessing foreign direct investment continue in the ICA. Beyond the net benefit requirement, foreign purchasers may also be required to make undertakings to maintain output levels, employment, key functions (e.g., head offices) and use of Canadian-sourced components. The minister’s decision is not subject to judicial review and therefore he or she has practically unfettered discretion on the file.

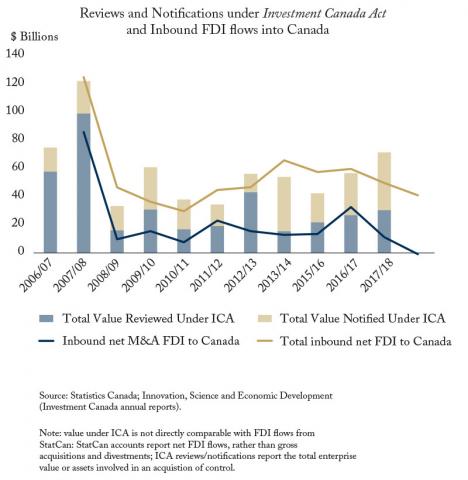

The ICA review process, and any undertakings obtained, are largely opaque. Although annual figures are published on the number and value of reviewed transactions, the minister does not disclose the extent of any undertakings or transactions that were withdrawn. Notably, the federal government has recently increased the thresholds for reviews; however, it appears that a significant amount of transactional value remains subject to review (see Figure 3).

The concern about restrictiveness to FDI – and particularly the unfettered discretion of the minister– has prompted past calls to reverse the current net benefit onus, including recommendations from the 2008 Competition Policy Review Panel (chaired by Red Wilson) and a recent C.D. Howe Institute report.

Reversing the onus would mean that Ottawa would have to show that a foreign investment would be a “net detriment”. This would require the minister to demonstrate the potential economic harm and also make the minister’s determination open to judicial review.

The federal government has talked up its desire to attract FDI but the largest restrictions remain in place. Ottawa should tackle this issue in its upcoming budget.

Grant Bishop is Associate Director, Research, at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.