From: Greg Peterson

To: Canadians concerned with food costs

Date: March 16, 2023

Re: Food Prices – Where is the Real Fat?

Food inflation, still rising as the all-items Consumer Price Index levels off, is attracting much attention.

Situated at the end of the supply chain, the big supermarket chains have been singled out as the main culprit for these price increases, with a particular focus on their reported profits.

This diverts attention from the bigger picture.

For one thing, not all food in Canada is sold by supermarkets and grocery stores, which have a 71-percent share of food sales according to the Feb. 28 retail commodity survey from Statistics Canada. Another 25 percent are by general merchandise stores such as Walmart and Costco. Also, more than a third of everything sold in supermarkets and grocery stores is not food.

So where do we look?

There is too much noise in the retail sector to draw a direct line from corporate financial statements to food inflation. Moreover, this discussion ignores how prices have evolved along the supply chain.

Stepping back, consider how food prices have changed over the course of the pandemic.

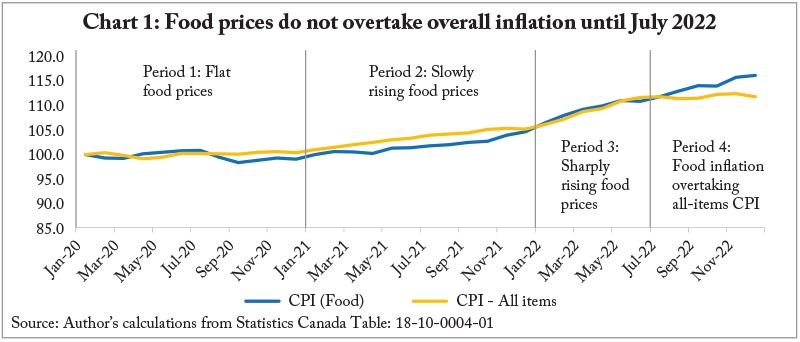

Food inflation can be broken down into four periods: early pandemic from January 2020 to January 2021, where food prices remained flat or were negative. From January 2021 to January 2022, food prices started an upward trajectory, increasing at a faster rate towards the end of the period. From January 2022 to July 2022, food prices tracked the same as all-items CPI and after July 2022, the CPI for food continued to rise, despite the levelling-off of the all-items CPI index.

So let’s look at where price increases have occurred along the supply chain.

Statistics Canada makes this easier by publishing price indexes for raw materials (the Raw Material Price Index or RMPI), at the factory gate after production (the Industrial Product Price index, or IPPI), as well as wholesale and retail service price indexes (the WSPI and RSPI, respectively).

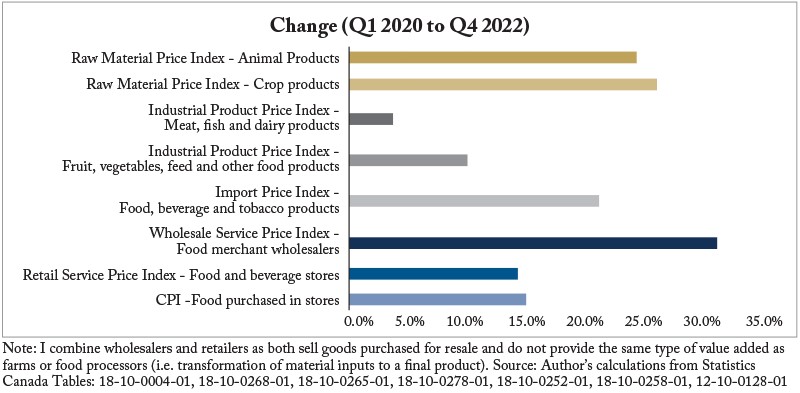

From the first quarter of 2021 to the third quarter of 2022 (the latest period for which there are data for all of these different prices), the price of food purchased at stores rose by 12.6 percent. That’s the bottom line for consumers – and the bottom line of the second graph below.

Meanwhile, at the top of the supply chain over the same period, prices of raw materials (both crop and animal products) and food imports rose at a faster clip. Food prices at the factory gate rose by less than the comparable CPI measure. The wholesale and retail service price indexes show the role these industries have on food prices.

The quarterly wholesale and retail service price indexes from Statistics Canada measure the price change for the services offered by these industries. More specifically, these indexes measure the difference between the average purchase and selling prices, or the margin price of goods purchased for resale.

Early in the pandemic, while food prices were stable, both wholesale and retail service prices started rising. From Q4 2021 onwards, retail margins were increasing at a slower pace than food CPI, however for wholesale food merchants, the Wholesale Service Price Index shot up.

Wholesale and retail price margins do not tell the complete story. Food is either domestically produced or imported. Early in the pandemic, there was considerable volatility in prices at the factory gate for meat, fish and dairy products, associated with the disruption in supply chains. While factory gate or IPPI for meat, fish and dairy products has stabilized, the similar measure for fruits, vegetables and other food products, as well as the Import Price Index for food, beverage and tobacco products has continued to rise.

Looking at the price increases over the whole period obscures that farm product prices for crops shot up especially fast between early 2021 and mid-2022. The increase in factory gate prices, up to the late spring of 2022 followed the movement in raw material prices for both meat and animal products. Since then, there has been a decrease in raw material crop prices, which has not been reflected in prices at the factory gate.

There is no doubt that Canadians are feeling squeezed as wage rates fell behind inflation. However, policy recommendations based on the profitability of food retailers will not make food more affordable. Members of the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food should keep in mind inflation along the entire supply chain, not just grocery stores. Some questions for their consideration include:

- Why has the recent decrease in the raw material price index for crops not been reflected in prices at the factory gate? Were food processors absorbing the significant increases in material input costs over the summer of 2022, or are they enjoying greater profits now?

- Wholesale margins have risen much faster than food inflation measured at the cash register (47 percent higher than Q1 2020). What is leading to these increasing margins (i.e. labour or other costs versus profits)?

- Retail margins have been rising since the start of the pandemic, at a pace aligned with food inflation (up until recently). While not rising as fast as other components of the supply chain, it would be good to know what is leading to these increases.

- Prices for raw materials have been more volatile and have increased at a greater pace than food CPI. Canadian farm operators are price-takers for many commodities. What is the sustainability of their operations where farm input prices have been rising faster than the prices of their products at the farm gate?

Greg Peterson is a former Assistant Chief Statistician at Statistics Canada.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.