From: Jon Johnson

To: Canadians Concerned about US Section 232 Tariffs

Date: August 16, 2018

Re: What to do about 232? Can Congress or the Courts Block Trump (Part Two)

Yesterday we considered congressional actions respecting President Trump’s use of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Today, the role of the US courts.

The American Institute for International Steel, Inc and others (AIIS plaintiffs) have filed a complaint with the US Court of International Trade (USCIT) maintaining that Section 232 is unconstitutional. They argue that the US Constitution confers legislative authority on Congress and cannot be delegated. While Congress can assign certain functions to the other entities, the US Supreme Court has held that Congress must “lay down by legislative act an intelligible principle” to which the performance of the function must conform. In two 1935 cases, the court declared provisions of the National Recovery Act unconstitutional as lacking an “intelligible principle” to guide, in one case the National Recovery Administration in formulating certain codes, and in the other, to guide the Secretary of the Interior in formulating certain regulations.

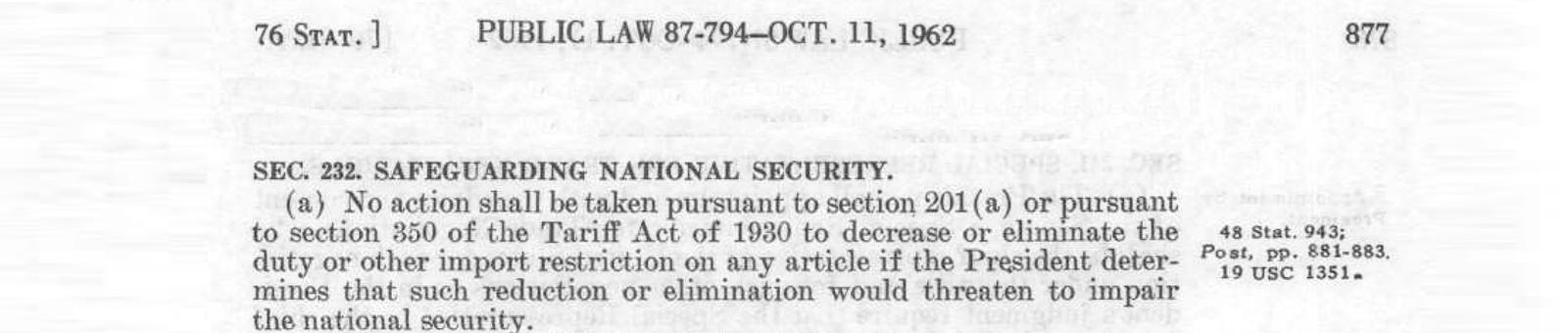

The Motion for Summary Judgment filed on July 19 by the AIIS plaintiffs maintains that Section 232 lacks an “intelligible principle” to guide the Commerce secretary in finding impairment to national security or to guide the president in what remedies may be applied, and hence constitutes an unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority. The definition of “national security” in Section 232 is so broad that practically any factor affecting the economy may be considered. The president’s authority to “adjust” imports is unlimited with no guidance. There is no guidance as to how to deal with imports from different countries or with the wide variety of uses of imported articles or adverse consequences that may follow from a proposed tariff or other action. The president is not bound by any remedial recommendations that the Commerce secretary may make. There is no opportunity for public input on actions the president chooses to take and no guidance respecting exceptions. The motion also underscores the fact that there is no provision whatsoever for judicial review of actions of the Commerce secretary or the president.

The AIIS plaintiffs have requested that the USCIT establish a three-judge panel because its decision is appealable directly to the US Supreme Count as opposed to having to proceed through intermediate appeal steps. The defendants, the US government and the commissioner of US customs and border protection, maintain in their response that a three-judge panel should not be appointed. The rules provide that the chief judge of the USCIT shall designate a three-judge panel if the constitutionality of an Act of Congress (here Section 232) is at issue. The response points out that only in the two 1935 cases referred to above have statutes been found unconstitutional by reason of lacking the necessary “intelligible principle”. The response also maintains that courts have declined to “enjoin presidential action when Congress’s delegation of authority is coexistent, as here, with the president’s inherent powers in the realm of foreign relations and national security.” The defendants maintain that the plaintiffs’ case for a constitutional challenge has a “steep uphill climb” and that the request should not be granted.

The outcome of the AIIS plaintiffs’ request for a three-judge panel will give a strong initial indication of where this constitutional challenge of section 232 is heading. A ruling in their favour will indicate that the USCIT considers that the constitutional argument from the plaintiffs may be valid.

Stay tuned.

Jon Johnson is a former advisor to the Canadian government during NAFTA negotiations and is a Senior Fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters