From: Jeremy Kronick and Nikki Hui

To: Concerned Canadians

Date: May 22, 2018

Re: Corporate Debt: The Next Financial Crisis Coming to Canada?

“Where will the next crisis occur?” The Economist recently asked with one of its typically attention–grabbing headlines. The article’s basic premise was that, despite high levels of corporate debt, investors continue to accept low returns. When investors in bonds and the like realize they have mispriced this risk, they will force a restructuring of the underlying corporate debt. The number of corporations that can handle this repricing is unknown. Pair this with already low levels of liquidity in bond markets post-crisis, and the outlook becomes ominous.

Here in Canada, the picture is rosier, but there are signs that we are not immune to some of these same trends.

The corporate debt to GDP ratio in Canada has increased from 50 percent to 70 percent since 2010, and while household debt tends to get most of the attention, average non-financial corporate debt growth since the financial crisis, at 9 percent, is 3 percentage points higher than the growth of average household debt. Rising interest rates will expose those corporations that have overindulged on debt.

Not surprisingly, as corporate debt levels increase, corporate bond ratings have fallen. In 2009, 57 percent of corporate bond issuers were investment grade (i.e., greater than BBB-). In 2015, that number fell to 42 percent. And, even within investment grade bonds, barely-investment grade BBB rated bonds have replaced much of the highest rated AAA/AA bonds. Furthermore, in 2017, Canada set a record for the value of junk bond issuances (i.e., those below BBB-).

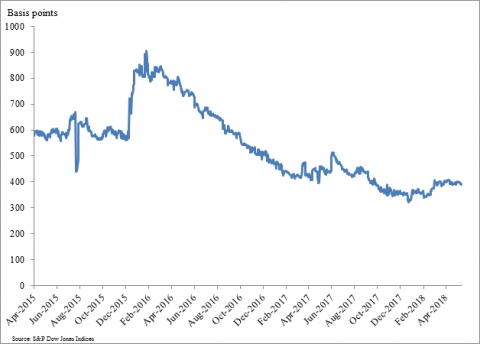

Amidst this riskier backdrop, one would expect investors to demand higher returns. But, alas, that does not appear to be the case in Canada. Indeed, high yield (below investment-grade) corporate bond spreads have fallen precipitously since the beginning of 2016 (see figure).

S&P Canada High Yield Corporate Bond Yield Option-Adjusted Spread

What this all means is we have a riskier corporate debt environment with investors that have potentially mispriced their exposure. If they awaken to this fact, or an economic shock exposes corporate vulnerabilities, we could see a forced restructuring of this debt. The mix of corporations who can and cannot handle this type of debt repricing is largely unknown. Additionally, any debt downgrade from investment grade to junk for corporations unable to service this repriced debt will make it more difficult for sellers to find buyers.

Inflaming this situation is already low levels of liquidity in the corporate bond market since the crisis. A Bank of Canada survey conducted at the end of 2015 found that approximately 60 percent of private sector respondents viewed the corporate bond market as illiquid or somewhat illiquid, and all of them felt that the market had become more illiquid over the previous two years.

Are there any positives to the Canadian story? There are. Debt-equity ratios have trended down, and sit at their 20-year average. In addition, corporate profits are above long-run averages, the share of short-term debt is falling, and cash positions of non-financial corporations have grown at 7 percent per year since 2010, sitting at record highs as a share of assets to GDP. The implication then is that corporate balance sheets in Canada remain healthy.

Perhaps investors feel that the positives outweigh the views of credit rating agencies, and if they are correct, then their decisions to accept lower returns are rational. If they are wrong, however, trouble could be on the horizon.

Jeremy Kronick is Associate Director, Research and Nikki Hui is a Researcher at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.