To: Canada’s Policymakers

From: Derek E. H. Olmstead and Adonis Yatchew

Date: July 29, 2022

Re: An Alberta Advantage: Carbon Pricing in the Wholesale Electricity Market

The Alberta wholesale electricity market provides an ideal setting to assess the effectiveness of carbon pricing in influencing firm behaviour and carbon emissions.

This is because production costs associated with carbon pricing flow easily and transparently through Alberta’s competitive wholesale electricity market, sending clear and timely signals to market participants. This Memo shows how recent increases in the price of carbon emissions, combined with a favourable market structure, have been a major factor in Alberta’s rapid and substantial emissions reductions in its electricity sector.

Before turning to the details, some background is required.

Alberta’s wholesale electricity market is simple: Indeed, it is close to the textbook model of supply and demand. Generators make hourly offers to supply a certain amount of electricity at prices of their choosing, at or above the marginal cost of production (the cost incurred by the generator to supply that power). Offers are ordered from lowest to highest and are dispatched in increasing order to meet demand. The last dispatched generator sets the price paid to all generators for each hour.

The wholesale market relies on competition to discipline the exercise of market power rather than on administrative rules. Investment in generation capacity over time is made by profit-seeking firms, which form expectations about hourly prices years into the future and decide whether these will be sufficient to recover their costs and provide a fair return for their investment. Unlike any other province, investments are not guaranteed by taxpayers in the event poor decisions are made or assets become stranded.

Alberta began pricing carbon in 2007. However, the effective carbon prices were too low to significantly affect emissions. This changed at the beginning of 2018 with the introduction of the Carbon Competitiveness Incentive Regulation (CCIR) which has since been renamed the Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction Regulation (TIER Regulation). Among the 2018 changes were:

- the magnitude of the cost of carbon emissions increased such that the cost borne by high-emission intensity facilities (i.e., coal) was raised significantly above low-emission intensity facilities (i.e., natural gas);

- creation of a mechanism to limit the magnitude of costs borne by consumers while creating efficient marginal incentives (called an output-based allocation); and

- a clear upward trajectory of future carbon emissions costs.

As we document in a paper published in The Electricity Journal these recent policy changes have had important effects.

Absent abatement or sequestration technology, natural gas generally has significantly lower carbon emissions intensity than coal, though there is a range of intensities associated with both fuel types. However, without meaningful carbon prices, coal’s marginal cost of electricity production is generally much lower than natural gas. Up to about 2020, the effectiveness of carbon pricing was limited because the level of the price was not high enough to overcome this difference in production costs.

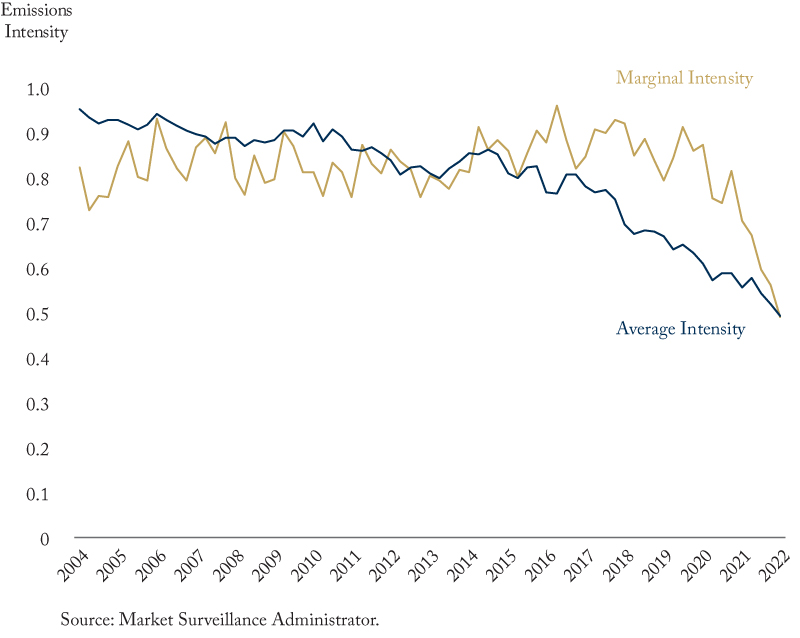

This changed as of 2021, by which time carbon prices had increased to the point that the production of electricity from coal was generally more expensive than from natural gas. This resulted in substantially greater use of lower emitting natural gas-fired generators and these generators increasingly being the marginal, price-setting technology in the wholesale market. As a result, average and marginal emissions associated with the production of electricity in Alberta have fallen dramatically in recent years as illustrated in the Figure.

Expectations of lower production and profits from coal-generated electricity resulted in a number of coal generators retiring much earlier – and without additional compensation from taxpayers – than had been planned under previously existing mandatory retirement dates. Given many of these generators converted from coal to natural gas, a roughly 50-percent emissions reduction per unit of electricity production was achieved with a minimal reduction of available capacity. It is now expected that there will be no coal generation remaining in Alberta by the end of 2023.

Carbon pricing aligns the public policy objective to reduce carbon emissions with the strong cost-minimizing incentives of profit-seeking firms. This has been accomplished in Alberta’s wholesale electricity market without the detailed and prescriptive regulation common in other jurisdictions, the costs of which are not transparent and often high and unintended.

When firms internalize the cost of carbon, and expect it to be stringent in the future, they will invest in technologies to gain or maintain a competitive advantage. Given the importance of low electricity prices to consumers and businesses, and electricity’s role in reducing emissions, it is essential that emissions reductions be made at the lowest possible cost. The experience of the Alberta wholesale electricity market clearly illustrates the effectiveness of carbon pricing in reducing carbon emissions.

Derek E. H. Olmstead is Administrator at the Market Surveillance Administrator and Adonis Yatchew is Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto and Editor-in-Chief of the Energy Journal.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.