From: Parisa Mahboubi

To: Canada’s ministers of education and skills development

Date: November 20, 2017

Re: High Education, Lower Literacy: What to Do?

Canada’s workforce has experienced a troubling slide in literacy and numeracy skills, despite higher levels of education and improvements in learning technology.

In my report last week I compared results of international surveys from 2003 and 2012 and found that Canadians’ skill levels declined across all age cohorts studied.

The work was based on the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, which measured basic information-processing skills such as literacy and numeracy in 40 countries. Only seven countries, including Canada, also participated in the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey, undertaken in 2003. Statistics Canada applied a complex procedure, both conceptually and technically, to re-estimate and re-scale the results to ensure comparability and reported them on a single scale, which I used in my report.

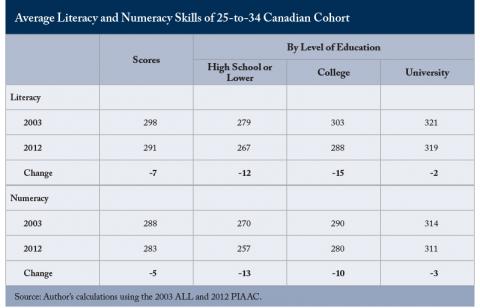

Aging and generational differences, such as in education quality and work environment, largely contribute to these declines. Skills erode with age at an accelerated rate, intensifying the negative impact of aging population on average performance. But as well, recent generations of Canadians achieved lower scores in literacy and numeracy, regardless of education level.

A more educated population does not necessarily guarantee more skills: educational attainment, which is generally defined as the highest degree an individual has completed, and skills attainment are trending in the opposite direction. More people are getting more education, but skill levels for every group fell between 2003 and 2012. Lowering the admission bar for post-secondary institutions may be among the factors contributing to declining skills levels.

I also found that average literacy test scores of individuals aged 55 years or older in 2012 declined at a faster rate than others. Therefore, slowing the rate of skills deterioration is important, especially among low-skilled workers who see sharper decline rates as they age.

Here are three recommendations to tackle Canada’s decline in skills:

- Provinces should focus their attention on education quality at all levels.

- Federal and provincial governments should encourage active learning and offer more targeted training opportunities for individuals that are at most risk to skills deterioration.

- Provincial and federal policymakers need to review their on-the-job training programs to ensure their effectiveness.

Improving these policies will help develop a more skilled workforce and would drive broader prosperity and economic growth with positive social impacts.

Parisa Mahboubi is a Senior Policy Analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.