From: Bill Robson and Farah Omran

To: Canadians Worried about our Weak Trade Performance

Date: September 6, 2018

Re: We would sell foreigners more goods and services if we sold them less government debt

Notwithstanding a welcome improvement in Canada’s current account balance in the second quarter, our deficit over the past 12 months is still $50 billion. Chronic disappointments in our trade balance have led many commentators – Bank of Canada Governor, Stephen Poloz, for one – to lament the Canadian economy’s inability to rotate away from consumption, which has been booming, toward investment and exports, which have not.

Many explanations are on offer: Canadian firms too lazy or complacent to sell abroad; protectionism; transportation bottlenecks. But step back for a look at Canada’s economy as a whole – the balance between what we produce and what we consume, and the corresponding gap between national saving and national borrowing – and we can see a more holistic explanation for these disappointments.

A country’s balance of payments always nets to zero: flows of goods, services and capital in and out over any period must be the same. Donald Trump and other mercantilists may imagine that a country can run surpluses in everything. But in reality, the amount of goods, services, and assets foreigners will buy from us in a day, a month, or a year will equal the amount of foreign goods, services and assets we buy from them.

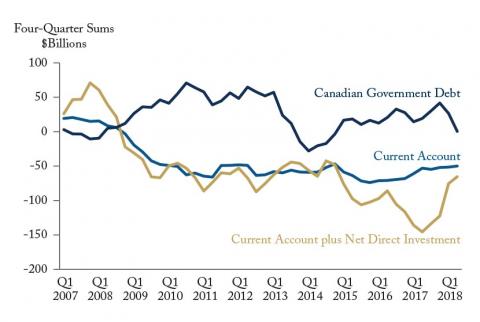

That fact allows some insights into changes in key parts of Canada’s external balance since 2007 (Figure 1). As is well known, lower oil prices after 2014 dented our merchandise exports, a major reason why our current account deficits have gotten worse. Less attractive prospects in the resource sector, and – more recently – uncertainty about trade and tax policy, turned our balance of foreign direct investment (FDI) negative.

Less noticed, but integral to the story, is that even as foreigners bought fewer of our exports and made fewer direct investments, they bought more Canadian debt. And the debt they bought was mainly government debt – reflecting the fresh enthusiasm of Canadian governments for deficits after mid-decade.

To repeat, the balance of payments must balance. To buy our debt, foreigners need Canadian dollars. So exporting that debt supported our exchange rate just as exporting goods and services would have done. If we had borrowed less abroad, the Canadian dollar would be lower – which would have raised the relative prices of tradable goods and services, encouraging an improvement in our trade balance, and made Canadian production more competitive, encouraging FDI. So the pickup in government debt sold to foreigners is part of the story of disappointments on trade and FDI.

In short, we have been exporting the wrong things. Rather than selling goods and services that would add to our wealth directly, or opportunities to invest that would boost our capacity to produce and export in the future, we have been selling government debt – about which the only certainty is that it will oblige us to pay interest in the future.

It is no coincidence that we are exporting more debt than we should, and exporting fewer goods and services than we would like. Canada’s exports and inward FDI have been weak partly because our governments’ deficits have been crowding them out. If we want to see more happy balance of payments numbers, less government borrowing would help.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.