From: Tammy Schirle and Mikal Skuterud

To: Canadians Concerned about the Labour Market

Date: October 20, 2020

Re: Long-term joblessness: a significant policy challenge on the horizon?

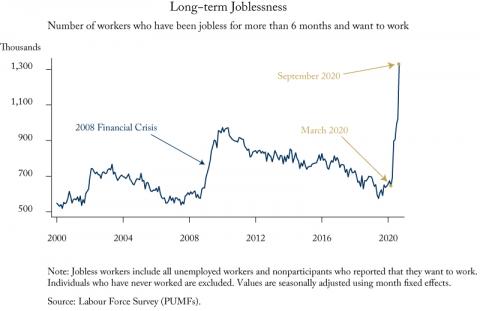

Between March and September 2020, the number of Canadians who have been jobless for more than six months increased by 107 percent, far exceeding the peak increase of 37 percent over the same length of time in the 2008 financial crisis.

This exceptional increase in long-term joblessness, a measure that is more inclusive than the more common measure of long-term unemployment, reflects the persistent impact of COVID-19 shutdowns, the ongoing impact of the health crisis, its impact on workers’ expectations of recall by past employers, and childcare challenges facing parents.

With more than 1.3 million Canadians out of work for more than six months, what should policymakers be prepared for?

First, available evidence suggests that the longer workers are jobless, the less likely they are to make successful transitions back to employment – a phenomenon known as negative duration dependence. Part of the reason appears to be employer preference: a 2013 study examined callback rates on fictitious resumes sent to real job postings, and found that employers preferred applicants who were recently unemployed over employed applicants, but strongly discounted the resumes of applicants who had been jobless for more than six months.

Second, there is clear evidence that workers displaced from their jobs (due to firm closures and mass layoffs) face significant earnings losses, but those losses depend on how long it takes displaced workers to regain employment. In addition to the loss of earnings during a non-employment spell, a study of UK wage losses found that workers with longer non-employment spells earned significantly lower wages in their new jobs than in their pre-displacement jobs.

How relevant is this evidence in the current crisis? We should expect significant losses, but there is some reason to be optimistic that long-term effects may be muted.

First, a higher proportion of the current long-term jobless are awaiting recall than usual. In particular, 9.8 percent of September’s long-term jobless were awaiting recall from their previous employer. For comparison, only 1.5 percent of the long-term jobless were awaiting recall in March 2020, and 1.2 percent in September 2019.

Second, the increase in long-term joblessness has been concentrated among young workers. In particular, 40 percent of the long-term jobless in September were between 20 and 35 years of age, compared to 32 percent in September 2019. There is some evidence younger workers may find it easier to recover as jobs re-open. For example, Morissette and Qiu found that older and long-tenured workers, particularly those in manufacturing, fare substantially worse than other groups when they are laid off. Perhaps younger workers – with more years ahead of them – have greater incentives to invest in new skills as part of their recovery efforts, through education or on-the-job training.

Third, once the health crisis has passed and recruitment ramps up, employers may rely less on the length of joblessness as a signal of a job applicant’s suitability, given the exceptional circumstances workers are currently facing in the labour market. This would improve the chances for the long-term jobless.

Despite our reasons for optimism, we still think policymakers should respond quickly to counter further growth in long-term joblessness. Ignoring such growth is risky: long-term disengagement from the labour market of a large cohort of young people may carry a high price for young workers. Some young workers will independently seek out opportunities during this crisis: for example, 16.5 percent of the long-term jobless were enrolled in school in September 2020, but many will need support to find such opportunities, particularly those shifting to new occupations or industries due to structural labour market shifts. Early investments in their labour market attachment – whether training for jobs in growing industries, supporting formal education efforts, or matching workers’ existing skills with new occupations – should have high returns for workers in terms of their productivity and ultimately their wages.

Such investments to improve the future prospects of the long-term jobless may appear costly, but there are broader fiscal impacts to consider. At a time when provincial and federal governments are projecting massive deficits to manage the pandemic, we want to keep as many Canadians as possible employed, reducing their reliance on income support programs, and strengthening their ability to help bear the long-term fiscal burden of this crisis.

Tammy Schirle is Professor of Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University, and Mikal Skuterud is Professor of Economics at the University of Waterloo.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.