To: Canadians Concerned about Our Future Living Standards

From: William B.P. Robson

Date: March 29, 2019

Re: The Struggle to Grow Canada’s National Wealth

Every quarter, Statistics Canada publishes two sets of indicators rich in information about where Canada’s economy has recently been, and some clues about where it may go next.

The income and expenditure accounts, highlighting quarterly GDP, show what we collectively produced, earned and spent. They get plenty of attention as the economy moves through booms and busts. Forecasters watch those numbers, partly because they know the Bank of Canada responds with interest rates to keep inflation on target. But 80 percent of GDP is consumption: most of what gets measured at the reporting date is what we used up. More is not necessarily better.

The second set, the national balance sheet accounts, highlight national net worth and show how our spending and saving, and changes in the value of assets such as natural resources, affected Canada’s national wealth. They get less attention – and could get usefully get more. What gets measured at the reporting date is the wealth Canadians own and work with, as households, as employees and owners of businesses, and through our governments. That tells us at least as much as last quarter’s spending about how prosperous we will be in the years ahead.

The income and expenditure accounts that came out at the beginning of the month told a story of an economy that was struggling. GDP barely grew in the fourth quarter of 2018, with business investment and net exports sagging.

The companion national balance sheet accounts that came out mid-month also told a story of an economy with problems. Canada’s net worth fell between the end of September 2018 and the end of the year – a decline in the value of natural resources being the headline bad news.

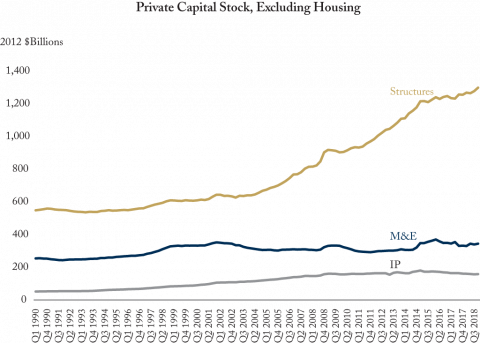

Swings in natural-resource prices are largely out of our control, and often reverse in time. Other elements of wealth, by contrast, are the results of our own actions, and have key implications for our economic future. In particular, the capital we build with our saving – the non-residential structures, machinery and equipment, and intellectual property that could raise our productivity and our incomes in the years ahead.

On that front, some news was good. After a flat period, the stock of private non-residential capital – buildings and engineering structures – has grown over the past year. Equally encouraging is an expansion of public-sector non-residential capital – evidence that governments’ expansive talk about infrastructure investment is actually translating into action.

Unfortunately, however, other news was dreary. As the weak business investment numbers in the income and expenditure accounts prefigured, our stock of private machinery and equipment is wearing out as fast as new investments are adding to it. After adjustment for inflation, it has not grown in four years. Canada’s stock of private intellectual property products has run down over the same period: our investments in software are not keeping pace with obsolescence (see Figure).

These capital stock numbers, as much as anything in the national balance sheet report – and more than most of what was in the national income and expenditure report – portend a tough period ahead for Canadians. While more buildings, engineering and infrastructure will help, Canadian workers need machinery and equipment, and less tangible assets such as apps and other software, to boost their output, earn higher incomes, and compete in a world where other countries are equipping their workers better.

A major reason for the disappointment that greeted last week’s federal budget was that it featured so much consumption-oriented spending, and neglected measures that would boost saving and capital stock.

As we get Statistics Canada’s quarterly indicators through 2019, we will inevitably have one eye on the income and expenditure accounts, and the ups and downs of spending will doubtless prompt comments on the success or not of federal initiatives to support the economy. Let’s keep the other on the national balance sheets. In the long run, our prospects for prosperity – and the true test of the wisdom of Ottawa’s fiscal policy – depend on national wealth. When it comes to wealth, more is indeed better.

William B.P. Robson is President and CEO of the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.