From: Parisa Mahboubi and Mikal Skuterud

To: Marco Mendicino, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Date: March 10, 2021

Re: An Economic Reality Check on Canadian Immigration (Part II)

Our memo yesterday outlined how the federal government effectively abandoned its ranking system for economic-class immigrants as it tries to reach its ambitious 2021 targets.

What are the potential risks and consequences of forgoing entry standards to increase immigration levels? And are there reasons to believe these risks may be acute during an economic crisis?

We know from Canadian research that increasing immigration, even in a strong economy, depresses the earnings of new immigrants during their first years in Canada. What is less clear is to what extent this effect reflects increased competition for jobs, as opposed to “quality-quantity” trade-offs in the admissions of new immigrants.

A recent C.D. Howe Institute study points to those trade-offs in admissions of international students to Canadian post-secondary institutions. As colleges and universities have reached deeper into international applicant pools over the past two decades, relative labour market earnings for those graduates have declined relative to both Canadian-born graduates and new immigrants with foreign education.

But this trade-off not only imposes a constraint on postsecondary institutions; it is built into the Express Entry system for screening economic-class immigrants. Increasing immigration levels necessarily requires lowering Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) cut-offs, and we know that CRS scores matter for immigrants’ integration prospects.

C.D. Howe Institute research shows that CRS points for English/French skills are highly predictive of immigrants’ economic integration success. In fact, the CRS language criteria are arguably not sufficiently rigorous as candidates with lower scores see significant challenges in transferring their skills into productive employment in Canada.

Is there any evidence that immigrants may also “crowd out” the job prospects of workers already living in Canada? While Canadian researchers have tended to shy away from this question, owing in large part to the inherent identification challenges, the international literature provides one possible outcome: those with substitutable skills are most likely to be adversely affect, while those with complementary skills may benefit.

A study in the November 2020 issue of the Canadian Journal of Economics provides a timely example. Examining a US policy change extending access to work permits for international students with master’s degrees in STEM fields, it found that increases in foreign-student labour supply in US labour markets reduced the employment rates of US-born recent STEM master’s graduates, but slightly increased the earnings of experienced US-born STEM workers.

Is there any evidence that the adverse effects of raising immigration levels may be exacerbated when domestic labour markets are weak?

On this question there is little evidence simply because it is unusual for countries to significantly increase immigration levels during recessions, for good reason.

There is, however, one telling Canadian episode. Between 1996 and 2001, Canada deliberately targeted immigrants with educational backgrounds and work experience in information technology (IT) and engineering. Employment in the computer and telecommunications sector grew by more than 50 percent compared to 12 percent across all sectors. But the 2001 bursting of the dotcom bubble had a large adverse effect on recent immigrant earnings, a Statistics Canada study showed. Even four years after arrival, average earnings were 25 percent lower than those who arrived in the mid-1990s.

We now also know that recent immigrants have experienced greater job displacement during the current COVID crisis, and have lower re-employment rates, leading to the return of some recent immigrants to their home countries. This reflects both their shorter job tenures, as well as the fact that more were likely working in low-wage sectors where employment losses in March and April were concentrated, and where current job vacancy rates are lowest.

The hard reality is that significantly increasing immigration in 2021 will have distributional effects – there will be winners and losers. To identify the biggest winners, you need only identify the loudest proponents: big business, real estate developers, banks selling mortgages, and immigration law firms. But waiving CRS standards for the sake of hitting ambitious admissions targets will undoubtedly increase competition for scarce low- to medium-skill jobs in those sectors hit hardest by this pandemic.

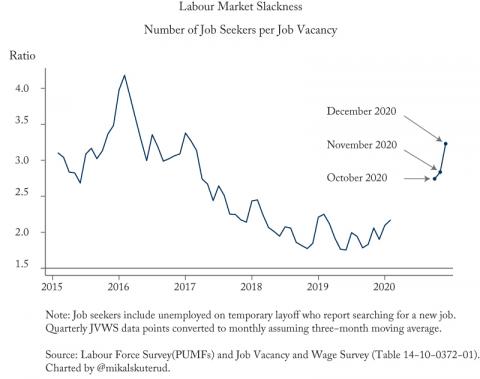

It is difficult to predict when Canada will return to tight labour markets. In December there were 3.23 jobless workers for every job vacancy in Canada, up from 2.74 in October (Figure 1). With the wind-down of government supports like the CEWS on the horizon and 500,000 workers displaced during this pandemic who have now been jobless for more than six months, the challenges ahead are already significant.

A decline in immigrant applications and entries when our labour markets are weak is a natural market adjustment, not a failure of Canada’s immigration system. Undoing this adjustment at all costs will have consequences. The Canadian economy had the capacity to absorb increased immigration levels prior to COVID-19, and will again. But now is not yet the time.

Parisa Mahboubi is a Senior Policy Analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute and Mikal Skuterud is Professor of Economics at the University of Waterloo.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Figure 1: