Along with rampant spending, erratic tax changes, and mounting debt, the federal government is developing another bad fiscal habit: its budgets are getting later.

The government has announced that it will present its budget for the 2024-25 fiscal year, which runs from April 1, 2024 to March 31, 2025, on April 16. By then, we will be more than two weeks into the fiscal year. That is too late.

The record of the Liberals under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was somewhat better before that. While only one of the four budgets they delivered from 2016-17 to 2019-20 appeared before March—and not by much: it came out on Feb. 27, 2018—none appeared after April 1. But their overall record is bad. Of the budgets they should have presented since their election in 2015, only half appeared before the start of the fiscal year.

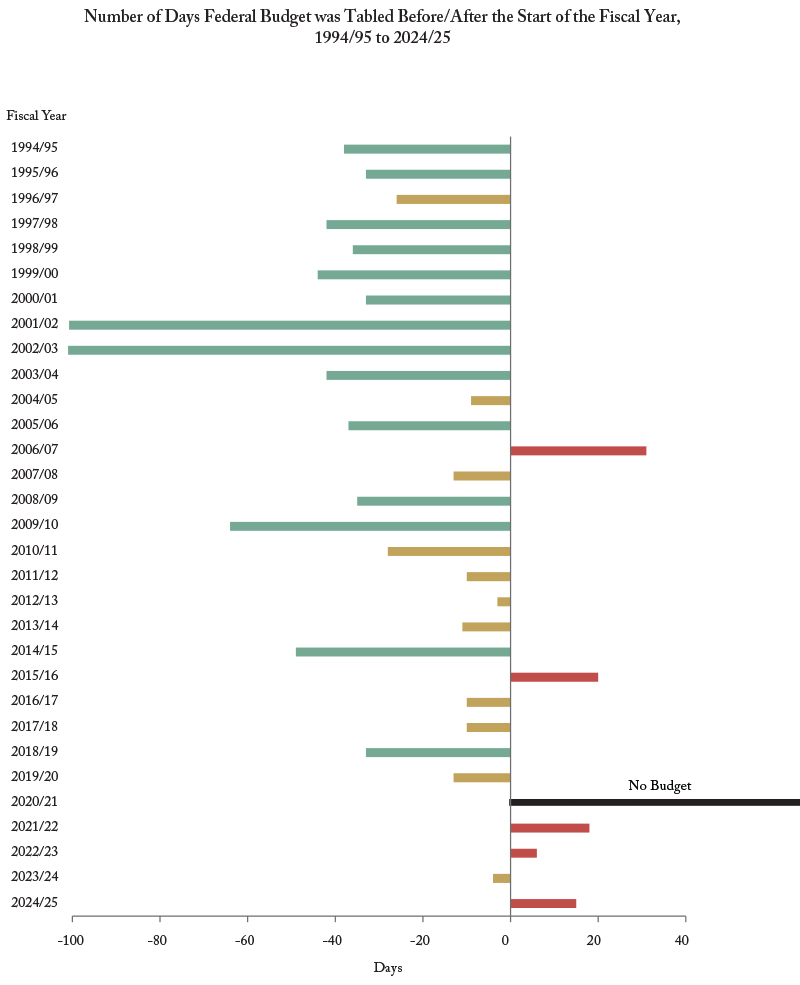

It has not always been like this. The Conservatives under Stephen Harper delivered 10 budgets (treating the post-election budget of June 2011 as a repeat of its pre-election counterpart in March). Their first, for 2006-07, was late—a consequence of their being elected in January 2006—as was their last. Of the other eight, five appeared in March, two in February, and one in January. The Liberal governments under Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin delivered 12 budgets (treating the pre-election update of October 2000 as the budget for 2001-02). All appeared before the beginning of the fiscal year, and most were well before—only two were as late as March. The update ahead of 2001-02 and the budget for 2002-03 appeared before Dec. 31 of the previous year—a degree of promptness and preparedness that would now be remarkable (the figure shows budgets delivered before March in green, budgets delivered in March in yellow, and budgets delivered late in red).

This should not be remarkable. We should not be used to MPs ratifying spending and tax changes that occurred weeks or months earlier. We should not be used to MPs voting on the main estimates—their unique opportunity to scrutinize individual government programs—weeks or even months before they see how those programs fit, or don’t fit, into the bigger picture of revenue, expense, deficit, and debt. We should not be used to governments treating Parliament like an afterthought, in financial management or anything else.

Nor should we expect disrespect for Parliament’s role in stewarding public funds to coincide with responsible stewardship of public funds. The record says otherwise. Canada’s previous experience of chronically late federal budgets occurred under the governments headed by Pierre Trudeau. Of the 18 budgets those governments delivered, only five preceded the start of the fiscal year. By the end of that period, the federal government was financing more than one-third of its spending by borrowing—a legacy of deficits, and mounting debt and interest that took almost two decades to redress. The fact that we are again seeing late budgets and irresponsible fiscal policy does not seem like a coincidence.

If governments will not produce timely budgets on their own, MPs need to force the issue. If they will not do that, Canadians need to elect different ones. A commitment to produce budgets well before the start of the fiscal year would be a good plank in a future election platform. If it came along with a commitment to a balanced budget, even better. We could have greater confidence in both.

William Robson serves as CEO at the C.D. Howe Institute, where Nicholas Dahir is a research officer.