Double the Pain: How Inflation Increases Tax Burdens

by William B.P. Robson and Alexandre Laurin

- Inflation and taxation are a painful combination. Money losing its purchasing power hurts on its own, but tax provisions that ignore inflation can multiply the pain for earners, savers, and recipients of benefit programs as well.

- This E-Brief identifies problematic interactions between inflation and taxes and highlights some that governments could address, notably by indexing various thresholds and amounts. Automatic increases in line with consumer prices are better than ad hoc changes, which governments often present as tax relief, even if they leave taxpayers no better off.

- Critics of specific tax provisions with bad economic effects may welcome the shrinking of their real value by inflation, but explicit discussion and decisions are more transparent than arbitrary erosion.

- Inflation hurts. Taxes should not make it worse. Now would be a good time for some changes to lessen the pain.

We thank Nicholas Dahir for research assistance, as well as Daniel Schwanen, Jeremy Kronick, Brian Ernewein, William Molson, Nick Pantaleo, Jocelin Paradis, Jeffrey Trossman, Kevin Wark and anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts of this report and publications on this topic by us. Responsibility for any errors, and for the analysis and conclusions, is ours.

Introduction and Overview

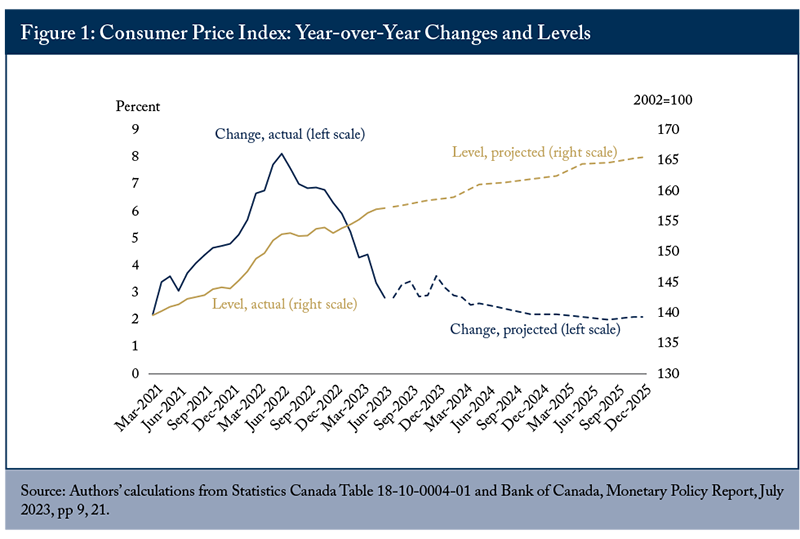

The year-over-year increase in the consumer price index (CPI) rose above the Bank of Canada’s 2 percent target in March of 2021, and hit a four-decade high of 8.1 percent in June of 2022. Although the year-over-year increases have since subsided, even the continued return to target in the Bank of Canada’s own projections implies substantial losses of purchasing power. The Bank’s July 2023 Monetary Policy Report showed year-over-year increases in the CPI back to 2 percent by the summer of 2025. If that happens, the purchasing power of a dollar will have fallen about 15 percent since March of 2021 (Figure 1). If inflation proves more stubborn than the Bank projects, the loss will be worse.

Inflation is itself akin to a tax. From the federal government’s point of view, currency is a liability that bears no interest.

But the pain of inflation and taxation is bigger than the erosion of the real value of governments’ liabilities. Inflation interacts with various tax provisions, often increasing the tax bite, with little transparency or legislative oversight.

Some of the extra tax burdens created by inflation are hard to mitigate. Adjusting corporate profits and investment income received by individuals to tax only “real” income – that is, after deducting the portion of nominal income attributable to inflation – would create enormous complexity. Others are easier to mitigate. Many thresholds and other amounts – the thresholds for various tax rates in personal income taxes, for example – are straightforward to adjust for inflation.

This E-Brief catalogues various interactions of inflation and taxes that magnify the pain for Canadian taxpayers. We highlight the ones governments could address, notably by indexing various thresholds and amounts. We do not defend each of the provisions we examine – neither their existence nor their initial or current levels. We do, however, argue that erosion by stealth is the wrong way to proceed, even when it reduces the distortions of misguided provisions. We also warn against tax changes that would exacerbate the painful interactions of taxation and inflation, such as increasing the inclusion rate on capital gains.

Lower inflation is the most direct way to reduce these problems. However, the losses of purchasing power suffered while inflation is above target will be permanent, and some of the problematic interactions still exist – even if their effects build more slowly – when inflation is low. Governments should address the ways non-recognition of inflation hurts earners, savers, and recipients of benefits and avoid tax-rate increases or measures that would exacerbate them. Whatever the future rate of inflation, Canadians would enjoy the relief.

How Does Inflation Affect Taxes?

Money is useful partly because it serves as a unit of account.

Personal income taxation specifies thresholds in dollar terms. If the price level does not change, that is not a problem – people’s incomes will only move into taxable ranges, or from one tax bracket to a higher one, if their incomes rise. But if both prices and incomes rise, lower-income people whose nominal incomes have risen into taxable ranges, or people whose nominal incomes have risen into a higher tax bracket, will find themselves paying a higher share of their incomes in tax even if their real purchasing power has not risen.

Although the solution to this problem is relatively straightforward – index tax thresholds so that they rise with prices – many jurisdictions do not do it. A recent survey of 160 countries revealed that 131 of them do not (Beer, Griffiths, and Klemm 2023). Irregularly adjusting thresholds, or increasing them but at a rate lower than inflation, can be a politically convenient method to effectively increase taxes in real terms while creating the illusion of tax reductions. Only nine countries, including Canada, have legislation or regulations in place mandating automatic periodic adjustments in line with inflation.

While Canada stands out positively in this respect – the federal government and most provinces index all their personal income tax thresholds to the annual change in the CPI – Canada’s tax systems do not automatically adjust all thresholds. Some provinces index only some thresholds, or none. Alberta did not index its thresholds in 2020 and 2021. Manitoba did not index its tax system to inflation before 2017.

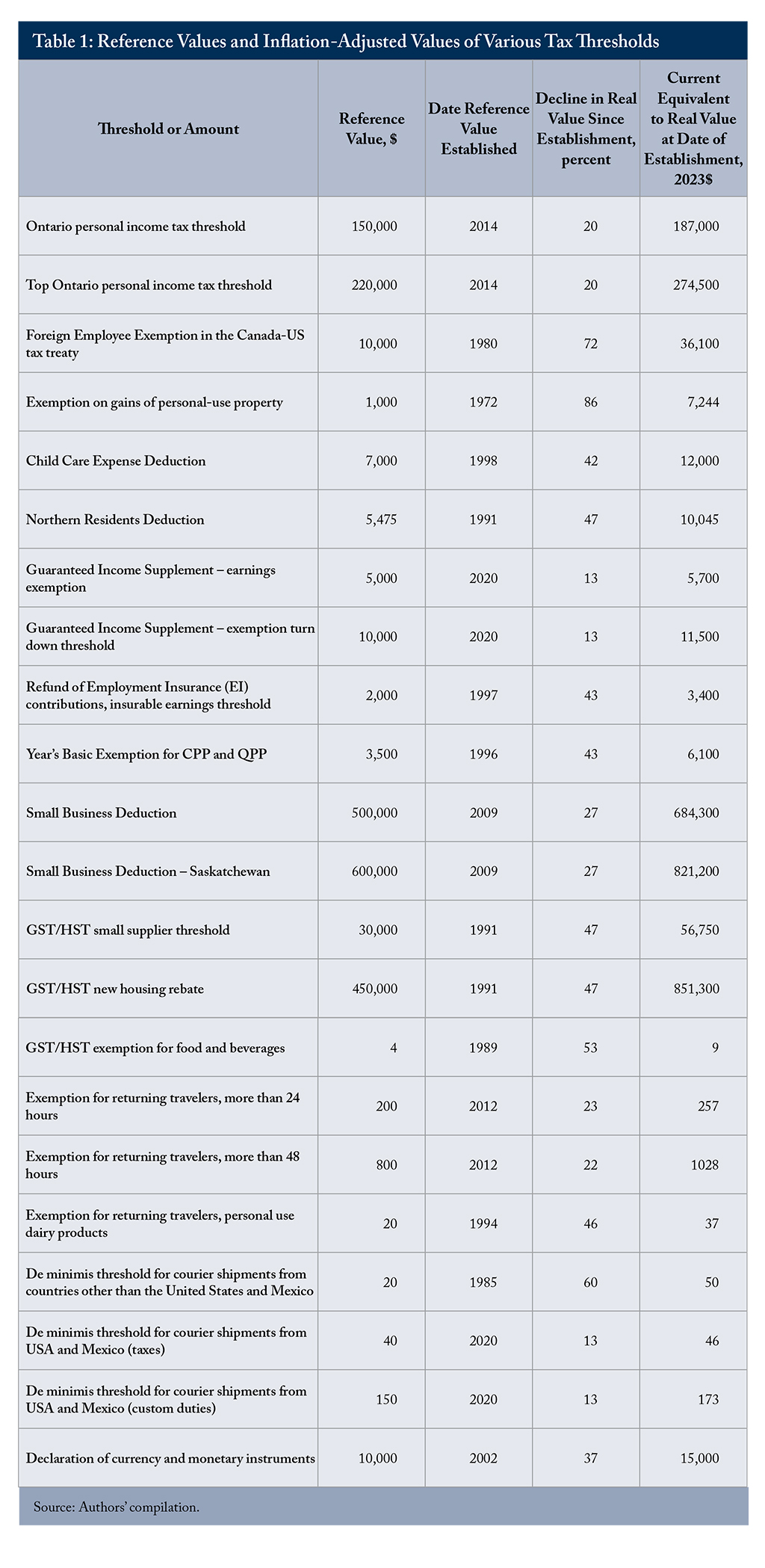

At the federal level, the maximum dollar limits under the Child Care Expense Deduction, although raised periodically since the deduction’s inception in 1972, are not adjusted for inflation. The maximum amount of childcare expenses that can be claimed per child under 7 years old is currently $8,000. Twenty-five years ago, the maximum was $7,000. Adjusted for inflation, parents would potentially be able to deduct up to $12,000 per child in 2023 – 50 percent higher than they currently can.

The maximum Northern Residents Deduction (NRD) is similar, in that it has increased at intervals, but is not indexed to inflation. The maximum residency claim was $5,475 in 1991 and is currently $8,030. If it had been annually indexed to the cost of living increase since 1991, it would now be $10,405 – 30 percent higher than its current amount. The second and latest increase was in 2016. The federal budget at the time justified the raise on the grounds of attracting skilled labour to northern and isolated communities. This is another example of how ad hoc increases in deduction amounts let governments take credit for cutting taxes when they are just mitigating part of the erosion of real values by inflation.

Other thresholds in personal income taxes get less notice, and have gone unindexed. A remarkable example is the $10,000 foreign employee exemption in the Canada-US tax treaty. After more than 40 years, inflation has cut its real value by almost three quarters – a major hassle for people who do minimal amounts of work in Canada. The $1,000 exemption from capital gains tax for gains on personal-use property such as jewelry, works of arts, and collectibles has gone unchanged even longer. Inflation has cut its real value by more than 85 percent since its establishment in 1972.

Tax credits, extensively used by Canada’s federal and provincial governments, are a mixed bag. Some reduce the burden of taxes paid, while others – notably refundable credits – are transfer payments in disguise.

The federal government indexes most of its tax credits and benefits to the CPI, but not all. The pension income credit, and the maximum tuition credits that tax filers can transfer to spouses or parents do not rise with the price level. Nor, notwithstanding ad hoc increases, does the First-Time Home Buyers’ Tax Credit.

The more complicated the structure of taxes and benefits, the easier it is for dissonance to creep into the system. Seniors’ benefits themselves – the actual payments – are indexed to inflation. But some provisions related to them are not. Since 2020, the Guaranteed Income Supplement for low-income seniors has exempted up to $5,000 of earnings from employment and self-employment, and half of the next $10,000 of such earnings, from its calculation. These matter – outside this range, the regular GIS claws back 50 cents per dollar of income, and for very low-income seniors, the GIS top-up claws back a further 25 cents. None of the clawback thresholds are indexed to inflation, meaning that rising prices push more seniors and more of their incomes into these 50 percent and 75 percent clawback ranges.

Another example of an unindexed provision in a generally indexed program is the refund of Employment Insurance (EI) contributions available to contributors whose insurable earnings are less than $2,000. That amount has not changed since its inception in 1997. In 1997 dollars, it is now worth $1,200 – far less than intended. A further example is the Year’s Basic Exemption in the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans. It has been $3,500 since 1996. In 1996 dollars, its value is now getting down to about $2,000. More earnings – and an increasing proportion of the earnings of low-income earners – are subject to CPP and QPP premiums every year, even if those earnings are not rising in real terms.

In addition to federal transfer programs, many provinces and territories provide cash benefits to individuals income-tested through the tax system. Macdonald (2021) reviewed seniors’ benefits, child benefits and sales tax rebates for all provinces and territories, and found that the majority of these amounts are not regularly indexed to inflation.

Business taxes have fewer graduated rates, but they have some, and a multitude of thresholds determine whether business incomes are taxed at all.

All of Canada’s senior governments tax small businesses at a lower rate than their general corporate income tax rates through a small business deduction, which applies to annual income up to $500,000.

The federal government imposes a $50,000 limit on passive income, such as income from property, in a private corporation, after which the small business deduction gets clawed back. The exemption levels under the federal government’s proposed interest deductibility limits for certain corporations are also specified in dollar terms, and will not rise with prices. Over time, they will bite harder than when they were originally established. Since 1998, sole proprietors may claim a deduction for premiums paid for private health services plans, limited to $1,500 for each adult household plan members and $750 for each child. Those limits are not indexed to inflation, and have never been raised.

Another interaction between taxes and inflation that matters for business taxation arises from the use of historical cost in calculating depreciation and valuing inventories.

Inflation lowers the real value of deductions for the depreciation of capital assets (capital cost allowances in Canadian terminology), since the historical costs on which depreciation schedules are based shrink in real terms. That boosts nominal income, and therefore taxes, even though capital assets will also cost more to replace. Beer, Griffiths, and Klemm (2023) show that the erosion of depreciation allowances in the presence of high inflation raises the effective business tax rate, and depresses business investment.

The impact of historical-cost valuation of inventories is more subtle, but it also increases measured profits and therefore taxes. For a simple and stark example, suppose a business produces a product for sale in one year using inputs bought the year before, and is only breaking even – using $100 in inputs to produce $100 in sales. With no inflation, the business would have no profits, and would pay no taxes on profits. But with inflation of 10 percent, its sales would be $110 and it would show $10 in profits. If the tax rate on its profits were, say, 30 percent, it would pay $3 in taxes, even though the real value of the costs it incurred to produce the product had also risen to $110, and it made no profit in real terms. Worse, its cashflows will be insufficient to cover the following year’s input costs.

The chronic inflation of the 1970s inspired many attempts to revise accounting practices for inflation, and success in that area might have prompted parallel changes in tax administration. But even in countries with much higher inflation than Canada, most of these attempts went nowhere.

Most consumption taxes are ad valorem taxes – being levied on nominal amounts, they rise (or fall) with the prices of the goods and services to which they apply. In general, declining purchasing power of money affects them less. But they also have thresholds that determine whether a business must collect the taxes or whether a transaction is taxable, and inflation erodes the real value of those. Whatever the wisdom of these provisions, it is problematic to have inflation, rather than explicit policy discussions and decisions, erode their value over time.

The $30,000 small-supplier threshold for collecting the GST has not changed since the establishment of the GST in 1991. After more than 30 years, inflation has cut its real value almost in half. Every year as inflation further erodes the threshold, more businesses must register and collect GST. Notwithstanding the advantages of registration for getting input tax credits, the falling real value of the threshold creates administrative and compliance costs.

The GST/HST new housing rebate allows an individual to recover some of the GST or the federal part of the HST paid for a new or substantially renovated house, up to a maximum of $6,300. The rebate phases out for homes priced between $350,000 and $450,000, and it is not available for homes exceeding $450,000. The maximum and the thresholds have not changed since the introduction of GST in 1991. In Canada’s major cities, the cost of new houses has risen to the point where the rebate is effectively obsolete.

The input tax credit for GST/HST on passenger vehicles – cars used by businesses, or pickup trucks not used to transport goods or equipment in the course of business – is only available in respect of costs up to a maximum. For vehicles purchased after 2000 but before 2022, the limits were $30,000 for regular vehicles and $55,000 for zero emission vehicles. They increased to $34,000 and $59,000, respectively, for vehicles purchased in 2022, and to $36,000 and $61,000, respectively, for purchases in 2023. Automatic indexation to inflation would be superior to the current practice of ad-hoc adjustments.

Another type of threshold for consumption taxes that has attracted attention since inflation rose in 2021 is the exemption for basic groceries and other goods from GST, HST and other sales taxes. Ontario provides a point-of-sale HST exemption for food and beverages that are prepared for immediate consumption, such as fast food, if the price is $4 or less. That limit was originally set in 1989, long before the HST replaced the provincial sales tax and federal GST. If that $4 exemption had kept pace with inflation, it would be $9 today.

The tendency for vendors to reduce package sizes as a disguised price increase (so-called “shrinkflation”) adds a wrinkle. The distinction between exempt basic groceries and taxable snacks typically relates to package size – a 500 ml container of ice cream or yogurt is a basic grocery, but if the manufacturer decides to avoid increasing the sticker price and reduces the container to, say, 450 ml, it becomes a snack. Smaller packages can result in shoppers paying HST or sales taxes on items that, except for the decline in volume, are the same as those they previously bought untaxed.

The federal government recently imposed a luxury tax on cars and aircraft costing more than $100,000 and boats costing more than $250,000. $100,000 is a very low threshold for aircraft, and may over time seem low for cars as well. In any event, inflation will subject more cars, aircraft and boats to tax over time, even if their real value does not increase.

As many investors have recently become painfully aware, inflation and taxes interact to reduce the returns to saving, often turning nominal gains into real losses.

Consider the taxation of interest and dividends. A one-year GIC recently yielded about 4.4 percent. With inflation also recently at 4.4 percent, that was a real return of zero. But income taxes hit the entire nominal amount. A tax rate of, say, 40 percent, knocks the GIC’s after-tax yield down to about 2.6 percent – a return that, in real terms, is a loss of about 1.8 percent.

Even when inflation remains within the target range set by the Bank of Canada, taxes may exceed what many would deem reasonable. A reasonable post-2025 scenario for many Canadians would be a real interest rate of 2 percent and inflation of 2 percent, with a marginal tax rate of 40 percent. Such a person would face an effective tax rate of 80 percent on real interest income – not a scenario that rewards saving.

Capital gains taxes also hit illusory gains. Most savers hold assets such as shares and real estate for years. When inflation is high, the bulk of the current dollar gain in their value is illusory. Capital gains are taxed at an inclusion rate of 50 percent. The 50 percent inclusion rate reflects several considerations, mostly relating to double taxation (because the retained earnings that increase share prices were taxed at the corporate level), the misallocation of resources arising from “lock-in” effects, and governments’ desire to encourage risk-taking.

Individuals investing in tax-recognized accounts such as defined-contribution pension plans and RRSPs do not have to worry about inflation affecting returns inside their plans, since these plans are tax-deferred. But when the tax becomes payable upon withdrawal, inflation can worsen the burdens in ways beyond those already discussed. Savers in defined-contribution pension plans and RRSPs must buy annuities or move their funds to RRIFs and similar vehicles when they retire or turn 71. Inflation has the effect of front-loading the real value of annuity or RRIF withdrawals. That can subject their recipients to higher tax rates early in retirement than would occur if they had an inflation-indexed annuity that provided equal cumulative value throughout their retirements, increasing the risk of poverty in old age.

Taxes on Imports and Border Regulations

Thresholds for payment of HST and customs duties at the border affect more importers and travelers as inflation lowers their real value. The current exemptions for Canadians returning from travel abroad – $200 for people who were out of the country for 24 hours or more and $800 for people out of the country for 48 hours or more – date from 2012. If they had risen with the CPI since then, they would now be 30 percent higher.

Some dairy products are subject to even lower personal exemptions. For instance, the duty-free limit for returning travelers bringing in cheese for personal use is $20, with amounts beyond that subject to a prohibitive 245.5 percent tariff. This $20 threshold is remarkably low and has remained unchanged since 1994. Notably, the real limit on cheese imports has not only declined due to price inflation but has fallen markedly relative to the value of most items that Canadians can import tariff-free for personal use.

The threshold for the value for courier shipments that can enter Canada duty-free from countries other than the United States and Mexico has been $20 since 1985. If it had risen with inflation since then, it would now be $50. The thresholds for imports from the United States and Mexico rose with the renegotiation of the Canada-US-Mexico Agreement in 2020 – to $40 for taxes and $150 for customs duties. But those amounts also will drop in real terms as inflation erodes their nominal values.

Although it is not an explicit tax measure, discussion of border regulations would not be complete without a reference to the threshold for declaring any currency or monetary instruments brought into the country. It has been $10,000 since 2002. If it had risen with inflation, it would now be more than $15,000. Perhaps $10,000 was too high – but changes in the threshold’s real value should be deliberate, not erosions by stealth.

How Can Governments Respond?

Our description of the interaction of inflation and taxation has touched on many examples of problems that are easy to fix, with indexation of thresholds heading the list. Notwithstanding the debatable wisdom of many of the relevant provisions, our starting position is that all thresholds for income and consumption taxes should rise with consumer prices from now on. Changes in the real value of thresholds should be explicit and transparent, not accidental by-products of monetary policy.

Thresholds that have not changed for years, or decades, need an update. While nothing guarantees that nominal values set years ago were “right” at the time, or that nominal values updated for subsequent inflation would be “right” today, thresholds that create administrative and compliance problems out of all proportion to their benefits, such as the $10,000 foreign employee exemption in the Canada-US tax treaty, should rise. Table 1 summarizes a number of the examples of thresholds we have discussed, showing their nominal value, the date of their establishment, the decline in their real value since then, and the current value that would exist if they had risen with the CPI since then.

One reason for preferring automatic indexation of thresholds to discrete changes is that so much discussion of tax policy in Canada lately puts vertical redistribution ahead of all other priorities. A discrete increase in the Ontario high-income thresholds would likely attract criticism for being regressive, even though adjusting for inflation would merely preserve the graduated structure intended when the thresholds were established. Questions about the desired level of progressivity of personal incomes taxes overall should not get settled through isolated arguments about inflation adjustments to particular thresholds.

Critics of some tax provisions that distort behaviour might welcome inflation’s erosion of their real value and consequent reduction of the distortions they cause. We sympathize: we have criticized the First-Time Home Buyers’ Tax Credit, and advocated its abolition (Robson, Drummond and Laurin 2023), for example, so might welcome its erosion by inflation. People concerned that the small business deduction discourages businesses from growing, or promotes tax-avoidance activities such as splitting businesses to keep them below the threshold for the regular corporate income tax rate, might see the erosion of its real value by inflation as a good thing. But outright abolition of distortions is more transparent than the arbitrary reduction in their value arising from over-loose monetary policy.

Dealing with problems affecting investment income is harder than indexing thresholds. Although the principle of indexing the cost base for investments subject to capital gains tax is straightforward, dealing with depreciation, improvements, inventories, and cost-averaging rules will create challenges. Indexed annuities are straightforward in principle, but annuity markets tend to be thin, and the difficulty of finding assets to back an indexed promise – a problem worsened by the federal government’s recent decision to cease issuing real-return bonds – means that frontloading of annuity payments’ real value will continue to be a problem. Providing tax recognition of the inflation component of interest and dividend receipts is technically daunting. Pending new ideas for doing so, a policy imperative is avoiding tax changes that would compound the damage. A salient example is proposals for increasing the inclusion rate of capital gains taxes, which would be a particularly bad move when inflation has already increased the real burden of capital gains taxes.

Conclusion

Inflation around 8 percent is something most Canadians had never experienced until last summer. Although inflation is now well down from its peak, it is still well above the Bank of Canada’s 2 percent target, and the Bank’s own projections do not show it returning to 2 percent until the summer of 2025. The shrinking value of our dollars is bad enough on its own, but inflation hurts us in more subtle ways, including through its interactions with taxes and government benefits.

The simplest way to reduce the pain from inflation’s interaction with taxes is to reduce inflation. But that takes time, and involves discomfort of its own. Meanwhile, governments should address the ways non-recognition of inflation hurts earners, savers, and recipients of benefits. Whatever the future rate of inflation, Canadians will enjoy the relief.

References

Bank of Canada. 2023. “Monetary Policy Report, July 2023.” July.

Beer, Sebastian, Mark Griffiths, and Alexander Klemm. 2023. “Tax Distortions from Inflation: What Are They and How to Deal with Them?” IMF Working Papers 23/18.

Canadian Tax Foundation (CTF). 2021. Perspectives on Tax Law & Policy. Volume 2. Number 3. September.

Chiang, Yu-Ting, and Jesse LaBelle. 2023. “Which Households Are Most Exposed to the Inflation ‘Tax’?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis On the Economy Blog. June 27.

Enache, Cristina. “Capital Cost Recovery Across the OECD, 2022.” Fiscal Fact No. 809. Washington: Tax Foundation. April.

Macdonald, David. 2021. “Not All Provinces Protect Their Poorest from Inflation.” The Monitor. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. December 13.

Robson, William B.P., and Alexandre Laurin. 2017. Hidden Spending: The Fiscal Impact of Federal Tax Concessions. C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 469. February.

Robson, William B.P., Don Drummond, and Alexandre Laurin. 2023. The Morning After: A Post-Binge Federal Shadow Budget for 2023. C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 638. February.