From: Almos Tassonyi

To: Municipal debt watchers

Date: May 19, 2020

Re: From the Black Death to the Depression to COVID-19: Using Debt to Overcome the Municipal Fiscal Squeeze

Despite the drumbeat of warnings of an imminent crisis in municipal fiscal ability to cope with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the silence from the provinces has been deafening.

British Columbia and Nova Scotia have provided some interim borrowing possibilities and others have eased the deadlines for municipal tax remittance or collection of provincial property taxes, but these minimal responses suggest that municipalities must now seriously consider their options to manage the pressure on their cash flow.

And the lesson from history, and current limited municipal debt levels, suggests cities today have debt room to get through the crisis.

Coping with fiscal crises is an age-old feature of municipal fiscal response. In the aftermath of the Black Death, the spokesmen for England’s medieval towns sought “to persuade the king that their burden of civic obligations was hopelessly onerous and the fiscal demands they had to meet were beyond their means,” given population shortage and an irretrievable deficiency of revenue.

Subsequently, tax-less finance became a feature of local finance in Victorian Britain, antebellum United States and in Canadian municipalities after the Great War. In the 1930s, municipalities that defaulted were placed under newly developed rules of supervision, the essence of which persist today as hard constraints on municipal fiscal flexibility.

Until the current crisis erupted, the general consensus on municipal fiscal health was that it varied from reasonably healthy, with some exceptions, to overwhelmingly asset rich with significant levels of fiscal surplus.

Municipalities have taken the initiative to reduce the cash flow pressures on local businesses and residents. However, there are immediate fiscal consequences to deferring tax payments, penalties and interest and utility fees as well as transit fare holidays and the decline in transit ridership.

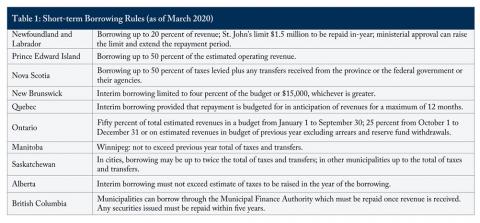

Generally, the municipal ability to borrow is constrained within the provincial-municipal hierarchical relationship. While municipalities throughout Canada face constraints on long-term borrowing, little attention has been paid to the context of short-term borrowing, that is, borrowing repayable during the municipal fiscal year (usually the calendar year). Municipalities are able to borrow on a short-term basis, generally with repayment or budgetary provision within a calendar year (see Table 1). Borrowing on an interim basis for capital purposes is also done to begin the financing of projects prior to the issuance of a long-term debenture.

Sources: Various statutes governing municipal powers

Hypothetically, if all municipalities could borrow up to 50 percent of their last year’s taxes, the result would be a cash infusion of more than $27 billion.

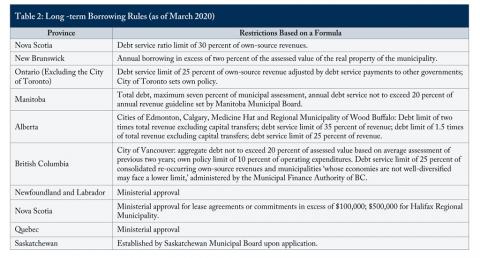

The borrowing rules imposed by provincial governments on municipalities are a reflection of the hierarchical relationship between the two levels of government that characterizes policy with respect to municipal finance. The existing set of rules has its roots in the crisis created by the Great Depression.

Most Canadian provinces use an ex-ante regulation or guidance from a provincial borrowing agency to control municipal borrowing (see Table 2).

Source: Slack and Tassonyi (2017) in Slack and Bird (2017)

Based on current data and rules in Ontario, municipalities in Ontario alone could borrow an additional $20 billion in long term debt before exhausting their regulatory borrowing room. Admittedly, borrowing to the hilt is not desirable practice but there is room for capital borrowing.

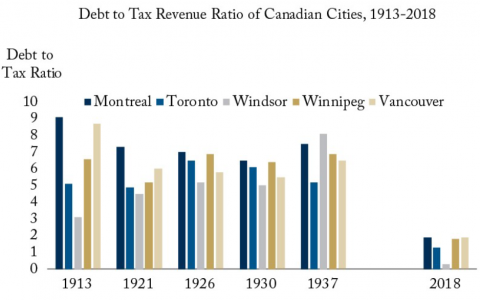

In contrast to the municipal situation prior to the Great Depression, municipalities in general are not overborrowed and have access to cash reserves. The debt to tax ratios in the major metropolitan areas of the country in the 1930s exceeded five to one compared to generally less than two to one today (see Figure).

Source: Rowell-Sirois Commission and Ontario Financial Information Returns.

There is little evidence of any reluctance on the part of investors in Canadian municipal bonds and the Bank of Canada has indicated its willingness to provide short-term liquidity.

Constraints on interim borrowing should be loosened by the provinces as an immediate step and municipalities should use enhanced borrowing power in the interest of smoothing cash flows and to buy time to establish policy as well as provide time for the economy to begin its recovery.

The rules on long-term borrowing for capital purposes do not appear to be an impediment to municipal access to funds, and act as a well-recognized seal of “Good Housekeeping.”

The major unknown will be the ability of municipalities to repay both this shortand long-term debt if property tax collections collapse as a consequence of the inability of the non-residential property owners to meet tax obligations for many years. Governments will have to adjust rules depending on the long-run recovery in fiscal capacity as more evidence becomes available on the extent to which the local tax base has been ravaged.

That’s a problem for another day – in the meantime, many cities can safely rely on debt to address their current needs if provinces allow sufficient flexibility in borrowing rules.

Almos Tassonyi is Executive Fellow at the School of Public Policy, University of Calgary and adjunct lecturer in the Department of Geography and Planning, University of Toronto.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.