From: Steve Ambler and Jeremy M. Kronick

To: Bank of Canada Watchers

Date: March 22, 2019

Re: The softer outlook for inflation

The last 365 days has highlighted the challenge of being a central banker. Last year, with inflation starting to consistently hit the 2 percent target, and the output gap indicating an economy finally getting close to capacity, the Bank appeared on its way to returning the overnight rate to the so-called neutral rate – where monetary policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive.

Fast forward to the present, and conditions are far less rosy. What happened, and what does the future hold?

In the first quarter of 2018, the Canadian economy hit the Bank’s 2 percent inflation target for the first time (at a quarterly frequency) since the fourth quarter of 2014. For the final three quarters of 2018, inflation remained at or above target, peaking at 2.7 percent in Q3.

A full calendar year of inflation at or above 2 percent is no small feat in post-crisis advanced economies; Canada had not accomplished such a feat since 2011. Supporting headline inflation were the Bank’s three core inflation numbers, which were mostly at or above target.

With one of the Bank’s output gap measures closing in 2017, there was now momentum to finally get the overnight rate back to neutral, estimated to be between 2.5 and 3.5 percent (the overnight rate currently sits at 1.75 percent).

Unfortunately, January’s inflation figures, along with a series of other macroeconomic data, and the Bank’s abrupt change in tone, have dampened this momentum.

Headline inflation in January fell to 1.4 percent, and all three core measures dipped below 2 percent. While the Bank announcement highlighted “temporary factors, including the drag from lower energy prices,” all three core measures slipping below 2 percent suggests the softening of headline inflation may not be simply tied to commodity prices. What else might it be, and is it a sign of more to come?

The evidence on economic growth suggests reasons for concern. Nominal GDP in the fourth quarter of 2018 grew by only 2 percent (annualized), after averaging 4 percent over the first three quarters. This slowdown in growth seems to be rearing its ugly ahead across the different GDP components, but is particularly severe in business investment, which fell in Q4. Much has been written on the topic of business investment, including by the C.D. Howe Institute, so we won’t go into detail here, but there is no denying its potential impact on economic growth, and therefore, inflation.

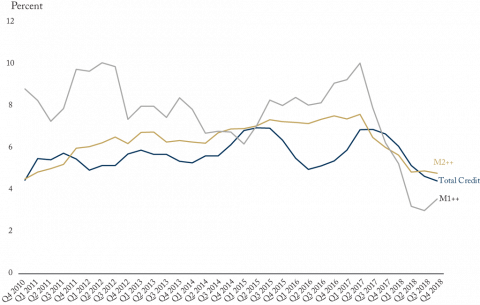

Two other measures concern us as we look ahead: credit and monetary aggregates. In our monetary policy retrospective we discussed the importance of looking at these measures in tandem. When they grow steadily together, GDP growth remains steady and inflation follows.

And growth rates of both credit and monetary aggregates have been quite steady for much of the 2009-2017 period. In the last year, however, these growth rates have fallen, (see figure) with narrow and broad money, M1+, M1++, and M2++, at or near post-crisis lows, and credit at its lowest point since 2010 (driven by household credit). As one of us showed back in January, the collapse of these monetary aggregate growth rates front-ran an associated fall in consumption growth in 2018, suggesting a continued sluggish economy could be in the offing.

In its March overnight rate announcement, the Bank highlighted the need to monitor household spending, oil markets, and global trade policy as it looks ahead to future rate increases. To that list, we would add monetary aggregates, credit, and the relationship between the two. Unfortunately, a longer list; but perhaps a more comprehensive one.

Steve Ambler is the David Dodge Chair in Monetary Policy at the C.D. Howe Institute, and professor of economics at the Université du Québec. Jeremy Kronick is associate director, research, C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.