From: Mawakina Bafale and William B.P. Robson

To: Canadians Concerned about Productivity

Date: July 18, 2022

Re: Canada’s Economy is Decapitalizing

Yet another alarming inflation number from Statistics Canada – 7.7 percent year-over-year in May– has underlined that something is seriously wrong with Canada’s economy.

Prices are rising fast because spending is rising fast while production is not. The capacity of our economy to produce is flat-lining because business investment has been so weak that the stock of productive capital per worker is falling. If we do not turn that around, the outlook for real growth in living standards in the coming months, years and decades is bleak.

The basic problem is chronically low business investment, which has been the highlight – or lowlight – of Statistics Canada’s quarterly GDP reports for several years now.

The cumulative effect of low rates of investment shows up in the national balance sheet accounts, which tally not flows but stocks: the assets and liabilities of households, businesses and governments. The balance sheet accounts make fewer headlines than the inflation and GDP reports, which is a shame because they tell us a lot about our economic prospects. Lately, they have been telling us that, thanks to business investment that is not even keeping up with depreciation, Canada’s net stock of capital is stagnating.

Economic growth has three main drivers: growth in the work force, growth in the capital stock, and growth of productivity. Growth in the capital stock and growth in productivity tend to run together. When businesses invest in new buildings, engineering structures, machinery and equipment, and intellectual property such as software, workers get better tools to work with, which enables them to produce more output and earnings per hour of work. The data show that our workforce is still growing, though not as quickly as in previous decades. But our stock of non-residential structures, machinery, software and other tools per worker is shrinking.

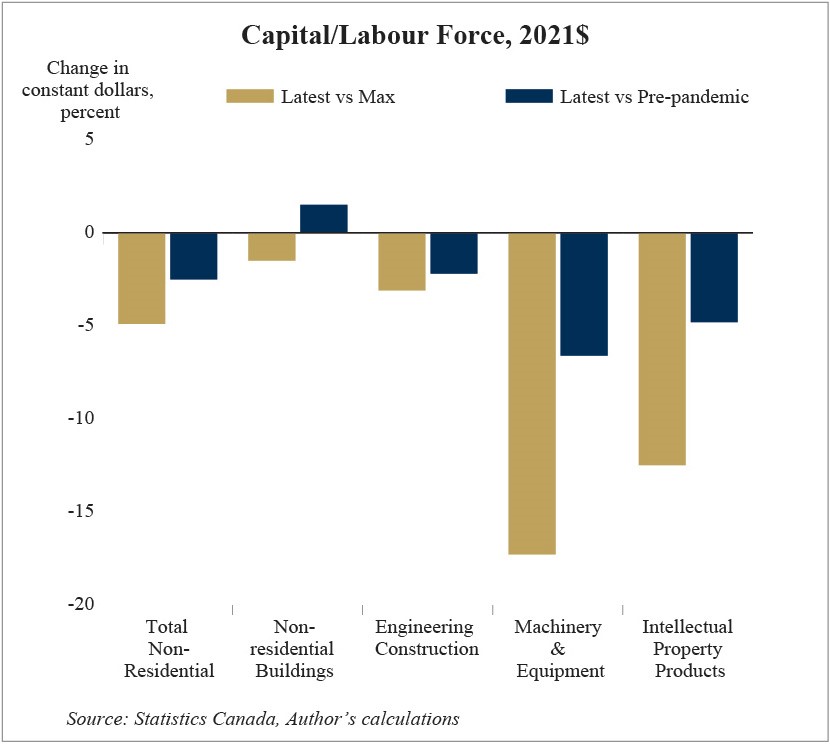

Compared to before the pandemic the real (that is, adjusted for changes in prices) stock of business capital per worker is down 3 percent (see Figure.)

The only type of capital that has grown faster than the workforce since the fourth quarter of 2019 is non-residential buildings. Capital per worker is down in the other major categories: engineering construction by 2 percent, machinery and equipment by 7 percent, and intellectual property products – the category thought to be spurred by COVID, to the extent of even possibly triggering a new period of prosperity – down 5 percent.

Extend the comparison further back and the numbers are downright alarming.

Canada’s stock of business capital per worker was declining even before the pandemic. Total business capital per worker peaked in the fourth quarter of 2015. Since then, it is down 5 percent. Compared to the workforce, each type of capital is down from its own peak around that time: non-residential buildings by 1 percent, engineering construction per worker by 3 percent, intellectual property products by 12 percent and machinery and equipment by 17 percent.

These numbers normally rise over time. Such a multi-year decline in the tools available to Canada’s workforce is very likely unprecedented. The only historical period where consistent data (if any existed) might show something similar is the depression of the 1930s. From the perspective of Canadian workers, our economy is decapitalizing.

One more release from Statistics Canada that should have gotten more attention than it did was June’s report that labour productivity fell 0.5 percent in the first quarter of this year – its seventh consecutive decline. No wonder growth in production is lagging growth in spending.

The 2022 federal budget did note the dire implications of low business investment, citing projections that growth in living standards in Canada would rank dead last among OECD countries over the next 40 years. If anything, however, federal initiatives since then – higher taxes on politically vulnerable businesses and products, lower limits on deductibility of interest on business loans, and confidence-sapping proposals for new regulation related to greenhouse gases, plastics and competition policy – will further discourage investment. Higher investment and robust economic growth seem to be low priorities in Ottawa these days.

We need changes in both tone and policy. Without them, the ominous decapitalization of Canada’s economy seems set to continue. Canadian workers need more capital – better tools – to raise their productivity and earnings. Otherwise, both the current expansion and our long-term living standards are in trouble.

Mawakina Bafale is a research assistant at the C. D. Howe Institute, where William Robson is CEO.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

A version of this Memo first appeared in the Financial Post.