From: David Johnson

To: Canadians concerned about school re-openings

Date: August 7, 2020

Re: Teaching with COVID Restrictions in Elementary Schools: What Can Be Done?

Last week, the Ontario government announced a plan to reopen elementary schools. Its plan requires very little additional spending, operates within the existing school day and space, operates exactly within existing collective agreements and, partly because of the choices above, defines a student cohort using existing class sizes. Boards must offer an online option to any parent who opts out.

Is there a more attractive alternative model with some of the same features as proposed by Ontario – and other provinces – that could be considered, given some of the early negative reactions to government plans?

I believe there is, if schools move to a two-shift split day schedule.

My proposal is a morning class from 8 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. (270 minutes) and an afternoon class from 1:30 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. (270 minutes), with one 40-minute nutrition break for students and an hour of cleaning between morning and afternoon. Elementary class sizes and the cohort size would average 17 students in Ontario. [1]

Students and teachers would take turns as required by space availability in the less desirable afternoon teaching shift. Depending on factors such as the uptake for online learning, the proportion of each school’s schedule that is in the afternoon could be as high as 50 percent or as low as zero. It would be a sensible choice to focus more afternoon shifts on older children, particularly in a K-8 school. The proportion of afternoon shifts, every other week or one week in three or four, would depend on the proportion of parents who choose fully online education and the amount of available space within each school. Each school or board could decide what works best for them.

School-based pre- and post-class childcare is a problem with both the two-shift day and in the government’s proposal. In the two-shift proposal, it is likely there would be no childcare before or after school. It is worth noting that in the government proposal, before and after school care exposes a student to a different cohort and the current school start and end times are already not convenient for many parents. It is perhaps surprising that the vast majority of parents find options outside the licenced child care spaces located in schools. [2]

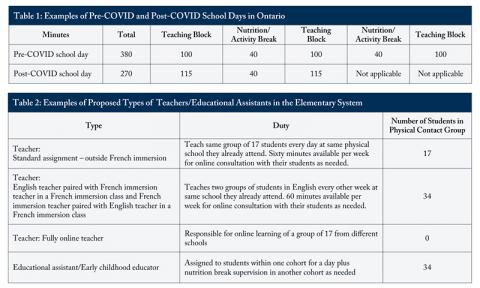

How would a school day look? In a pre-COVID school day in Ontario, each student attended school for 380 minutes with two 40 minute breaks. In the usual 380-minute school day, a teacher instructs 252 minutes, has 48 minutes of preparation time, an average of 16 minutes of supervision time, with the remainder of the day for lunch.

In my proposed post-COVID day, there would be two instructional periods of 115 minutes with one 40-minute break for students. [3] The students’ nutrition break might be supervised by the same EA, ECE or lunchroom supervisor every day either from their class or another class eating lunch at a different time. Teachers receive only one 40-minute break within the shorter instructional day. Their preparation time and part of their lunch comes outside the instructional day.

The post-COVID instructional day has 70 fewer minutes of instruction than the 300 minutes in the pre-COVID day, a significant loss. Some of these 70 minutes are made up in not losing class time beginning and ending a second activity break; by fewer changes of teachers; and having no assemblies or field trips. If professional development time was scheduled outside the shorter instructional day, then teaching on the seven PD days in Ontario would generate 1,610 additional minutes of instruction in the year.

How would my proposal look for elementary teachers, EAs and ECEs? Some teachers take a group of 17 non-French immersion students and teach those students every day. This teacher is exposed to only 17 students. [4] A French immersion teacher could be paired with a non-French immersion teacher with a class of 17 French immersion students. Students in immersion receive half their instruction in French and half in English on alternate weeks. This pair of teachers sees 34 different students over the two-week cycle. [5] Finally, a third type of teacher handles all the children from families who wish to opt out of physical school attendance, seeing no students in person.

A huge advantage of this proposal is that all teachers, EAs, ECEs and possibly lunchroom supervisors could be limited to exposure to a maximum of 34 students. A teacher could also choose to be exposed to zero students. The size of the cohort exposure of a typical student is also smaller, much smaller for students past Grade 3 and for many kindergarten students.

There may be other disadvantages. Is one hour a sufficient time to safely clean what ever classrooms are needed for the afternoon shift? There would be transportation complications. Perhaps students in urban high schools would have to use public transit, walk or use bicycles to free up needed bus space for elementary students. School administrators and secretarial staff as well as custodians would have to change work hours across the longer school day.

The reality is that, given the presence of COVID-19 in our society, many activities are being modified in ways that are not perfect. We all just have to try. This proposal seems feasible without the addition of vast resources to the elementary school system and has some advantages relative to the government’s proposal.

David Johnson is professor of economics at Wilfrid Laurier University and a C.D. Howe Institute Research Fellow.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

[1] In 2018-19 there were 16.50 students per elementary teacher in Ontario. Thus a cohort with a maximum of 17 for all students fits the proposal within existing teaching resources if almost all current teachers take a class as a unit of instruction. There were also 10,076.7 ECEs in Ontario schools in 2018-19 (and an unknown number of EAs in the entire elementary system). Some classes may need be slightly smaller to handle special needs students with EA resources allocated to that task and using teachers with some extra training. Then other classes would have to be slightly larger than 17. The central parts of the proposal would still work.

[2] In 2018-19 there was a total of 282,048 licenced child care spaces in publicly funded schools (an unknown number are pre-school spaces) and 977,371 students from junior kindergarten to Grade 5 in Ontario publicly funded schools. While these are important programs, it is clear the vast majority of parents do not use before and after school programs at schools.

[3] Breaks could be staggered or offset to reduce entry and exit congestion and playground congestion causing slight variation in the length of instructional blocks.

[4] Core French instruction in either model is a challenge. In the government proposal it is implicit that a core French teacher sees six classes for 40 minutes, between 100 and 200 students a day. One alternative is to place teachers with limited French in the primary divisions and teachers with better French in the junior division. Another possibility would see a cohort teacher guide their students through a French class supplied online. Having a supply teacher moving from cohort to cohort and even across schools is another issue. Is such a teacher more likely to be exposed to the virus and become a carrier?

[5] This reflects a presumed shortage of French immersion teachers if the cohort size is reduced to 17.