From: Adam Found and Peter Tomlinson

To: Public Finance Experts

Date: November 24, 2020

Re: Ontario Reforms its Business Property Tax

Can anything good come of the novel coronavirus? Examples are clearly scarce, but there’s one notable entry in Ontario’s 2020 budget. The budget announced long overdue reform to the province’s business property tax – generally known as the Business Education Tax (BET). Why reform it now? The budget says it’s to support recovery from the virus-caused recession.

As the budget acknowledges, the BET is effectively a “job killing” provincial tax levied at “unfair” rates. These defects go back to 1998, when the province removed taxing power from school boards.

Property taxes, including the BET, are among the fixed costs faced by businesses. As revenue falls in the recession, fixed costs imperil viability for many enterprises. To mitigate the threat, the budget cuts the BET by $450 million per year starting in 2021 – an 11.25 percent cut to the BET’s $4 billion annual base.

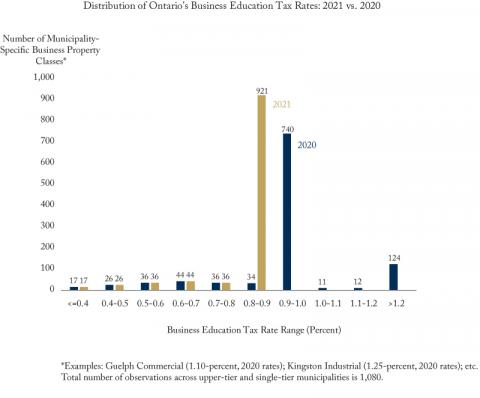

The distribution of the cut, however, is what gives the measure landmark reform status. The higher the BET rate now levied on a business, the larger its rate cut will be. School boards gave the province a wide range of tax rates in 1998, and much of this legacy range remains to this day. As the government’s rate-setting regulation indicates, the high end is generally at 1.25-percent of assessed value, although a few rates are higher (for example the 1.33-percent Ottawa industrial rate). As the accompanying figure shows, rates at the low end are under 0.40-percent. In urban areas, the low end is at 0.77 percent – the rate levied on commercial businesses in Halton Region.

The new rates will ensure that no business faces a higher BET rate than 0.88 percent next year, with rates below 0.88 percent evidently left alone. As a result, 95 percent of the province’s business assessment base will be taxed at a uniform 0.88 percent rate. Within the Greater Toronto Area, all industrial businesses will pay the uniform rate, as will all commercial businesses except those in Halton Region. A ceiling rate at the 0.77 percent Halton level would be ideal, but foregone revenue would be about twice the $450 million per year now budgeted.

As the budget correctly notes, the BET reform “will make the entire province more competitive.” How competitive will the new ceiling tax rate be? A tax rate of 0.88 percent means next year’s tax will be 0.88 percent of a property’s 2016 market value, given the five-year assessment lag scheduled for 2021. Major competing jurisdictions – including British Columbia, Alberta and many US states – have assessment lags of just one year. Apples-to-apples tax-rate comparisons need data not currently provided by Ontario’s assessment agency (MPAC).

The government could build on its BET reform by requesting MPAC to post ratios of assessment to market value on its website. Investors and the business community at large could then compare effective tax rates in Ontario with comparable rates in competing jurisdictions.

It’s important to note that school board spending is unrelated to whether BET rates in their districts are high or low. Thus the BET is “unfair,” as the budget acknowledges. Unfairness could be eliminated by increasing lower rates to 0.88 percent, but this is not a step we’d recommend. It’s better to leave the lower rates in place, as benchmarks for potential future reductions to the ceiling rate.

Leaving lower rates in place while reforming the overall rate structure requires tax cuts. As with the current government’s reform program, previous governments announced reform programs modeled along these lines. However, their tax cuts were to be phased in over eight years, meaning that full implementation was never guaranteed.

The last Progressive Conservative government had cut about $400 million annually by 2003, the sixth year of a phase-in program that ended with an election loss that year. The Liberal government had cut about $215 million annually by 2012, the sixth (and last) year of a phase-in program the government abandoned. And now the current government, avoiding a phase-in, will have cut $450 million annually when property tax bills go out a few months from now.

Adam Found is Metropolitan Policy Fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute and Peter Tomlinson is a consultant who has held Sessional Lectureships in Economics at the University of Toronto.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Source: Ontario Regulation 6/20