To: Canada’s Ministers of Employment

From: Parisa Mahboubi and Ivannia Irawan

Date: November 3, 2021

Re: Embracing Population Aging: Staying Young Through Life-Long Learning

Population aging – accelerated by improvements in life expectancy not least – has been an unpleasant reality for policymakers around the world as working-age populations dwindle and the costs of healthcare and pensions accelerate.

Canada’s ambitious immigration levels cannot fully deflect the demographic inevitability, and it should be looking at other responses to address the rising curve in its Old-Age Dependency ratio (OAD), the longstanding measure of those over 65 relative to the traditional working age population – 18 to 64.

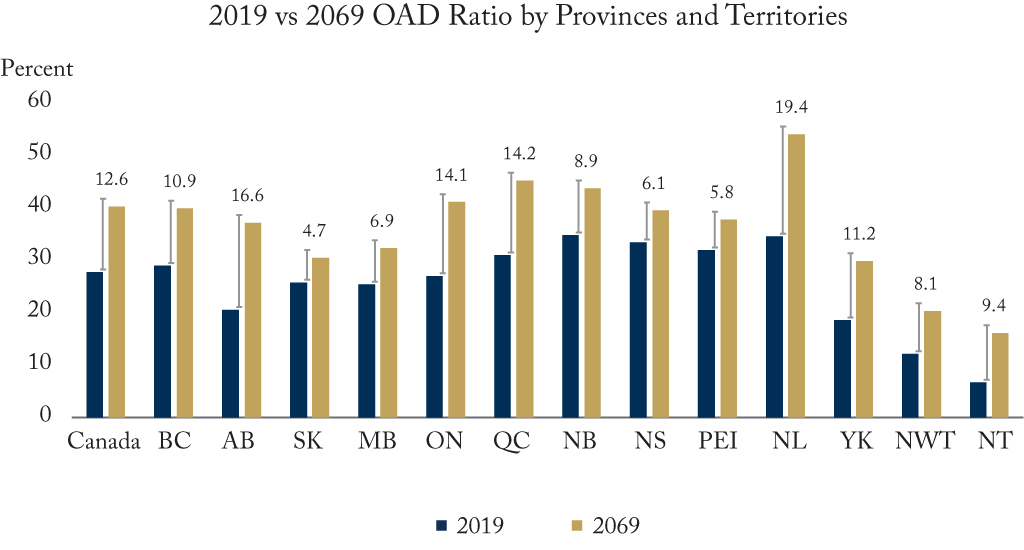

Canada’s ratio has jumped seven percentage points since 2010, sitting at 28.6 percent last year. And even with Ottawa’s plans to maintain immigration levels at one percent of population in the next couple of years, we project OAD ratio will keep rising for the next 15 years before it flattens around 38 percent, and settles about 40.3 percent by the end of our projection in 2069.

At the provincial level, even the big migrant destinations – Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec – see rising ratios, as outlined in the Figure. Alberta, which currently sits as the youngest province with a 20.6-percent ratio, is projected to hit 37.2 percent by 2069.

If Canada was to rely solely on immigration to address the impending labour force shortage, it would need to settle 2.85 million new Canadians immediately in order to return to the 2019 OAD ratio. And arrivals would need, on average, to exceed 1.7 million people annually over the next decade to maintain that OAD ratio.

One solution to mitigate the impacts of aging is encouraging later retirement. In fact, shifting the retirement age gradually from 65 to 70 over the next two decades would keep the OAD ratio around or below the 2019 level over the next five decades, presuming current immigration rates continue.

According to Statistics Canada, there has been a steady increase in the employment and labour force participation rate of Canadians ages 65 and over since 2000. Consequently, the average retirement age of all workers has increased by three years since 2000 to 64.5 in 2020 – yet still below its 1977 level of 65.1.

Timing of retirement depends on various factors such as economic conditions, pension and retirement policies, the flexibility of choosing between working or claiming pension, the ability of employers to legally terminate their employees at a certain age and the availability of flexible scheduling options.

The absence of adequate skills to adjust to labour market changes is another factor that may discourage seniors from delaying retirement or reduce their employability. Therefore, providing learning opportunities and training to older workers can improve retention and encourage later retirement.

And the seniors of 2069 are today’s teens and 20-year-olds whose prospects can only rise if we implant the mentality of life-long learning early on, ensuring a population not merely educated but also skilled. This strategy has worked in Singapore, which has seen its OAD almost double to 21.6 percent in the last decade. Its universities encourage life-long learning and industry-related skill upgrades to their alumni, which is supplemented by government lifelong learning programs. Meanwhile, in Japan, with the world’s highest OAD, later retirement has been a focus, even to the extent of encouraging seniors to start new businesses. Along with robotic innovations to lower healthcare costs, Japan encourages seniors to remain active in society and offers incentives to employers to hire workers past age 65. In 2020, about 26 percent of people ages 65 and over in Japan participated in the labour market, compared to just 14 percent in Canada.

Learning from Japan and Singapore, Canada too can start embracing population aging, creating the conditions for a senior population that generates economic activity instead of fiscal stress.

Parisa Mahboubi is a Senior Policy Analyst and Ivannia Irawan is an IMCO Policy Intern at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.