From: Pierre Lortie

To: Canadians concerned about competitiveness

Date: April 18, 2019

Re: Promoting Entrepreneurial Finance

Much has been written about the urgency of reviving economic growth and the need to halt the steady decline of Canada’s competitiveness relative to its peers. To a large extent, the decline in the dynamism of the Canadian economy is a consequence of low business investments in machinery, equipment, R&D and other intellectual property assets.

At first glance, Canada’s lacklustre performance on these dimensions is puzzling, considering the abundance of equity capital available to fund such investments

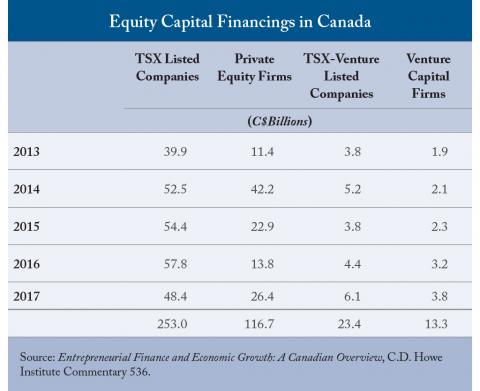

Equity capital is the fuel that helps firms scale-up and invest in fixed and intangible assets; it stimulates innovation, productivity and economic growth. In this respect, Canada appears relatively well positioned with regard to both public and private equity markets. The market capitalization of Canadian operating companies listed on a Canadian stock exchange is equivalent to about 140 percent of GDP, a level above the OECD average that is positively correlated with economic growth. My recent C.D. Howe Institute Commentary shows that the TSX stock market is complemented by a thriving private equity (PE) market. Between 2013 and 2017, PE firms invested $116.7 billion in Canadian businesses across all important industry sectors. In terms of venture capital firms’ investment as a share of GDP, Canada now ranks third behind the United States and Israel. In addition, the TSX Venture is one of the largest public venture capital markets in the world.

So where is the disconnect?

Increasing the number of high-growth small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is now a major focus for industry policy worldwide, as their significant impact on competition, innovation and productivity is increasingly recognized. But in Canada, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. Since 1997, both the entry rate of new firms and the proportion of high-growth firms in the Canadian economy have declined by more than 30 percent. Existing policies are proving ineffective, in part because they create an impediment to growth when Canadian companies list their shares on a stock exchange.

Consider the following: SMEs that go public lose their Canadian-controlled private corporation status; they are penalized by a jump in the federal income rate from 10.5 percent to 15 percent and a substantial decrease in the federal Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax credit for R&D from 35 percent to 15 percent. In addition, when they are listed on an exchange, companies are no longer eligible for a cash refund of the tax credit; instead, new technology-based companies must be content with almost worthless tax credits since, being in the development phase, they are not yet, or barely, profitable.

The first element of a comprehensive entrepreneurial finance policy must begin with the correction of this taxation bias that discriminates and penalizes innovative and high-growth companies that go public.

Second, the depth of Canadian equity markets needs to be increased to allow firms that have reached the growth stage characterized by product maturity, rapid customer adoption and revenue growth to reduce their reliance on sales to foreign investors and improve their chances of remaining independent. To this effect, serious consideration should be given to adopting a tax measure similar to the US Small Business Jobs Act of 2010, which provides for full exemption from federal taxation of capital gains realized on the sale of the shares of certain small businesses held for at least five years prior to sale.

Third, there is an important societal motive to ensure individual Canadians have the opportunity to benefit from the wealth created by high-growth firms during their early phase. In order to increase individual investor participation in Canadian stock exchange markets, the capital gains tax rates on shares issued by qualified SMEs when they list on a Canadian stock exchange and held by individual investors for a reasonable period of time afterwards should be reduced. For example, the tax rate could be reduced by 50 percent if the shares are held for more than 12 months, and go to zero if the shares are held for more than 36 months.

Fourth, to reduce the attractiveness of hollowing out high-tech and innovative companies through sales to foreign firms, and to encourage the growth of commercialization activities, the federal government should implement, in addition to the current tax incentive for R&D activities, a reduced income tax rate on the commercialization of intellectual property for which the companies have incurred expenditures. Many European countries have implemented this dual approach.

For entrepreneurs looking to either cash out or scale up, as well as private equity investors, the adoption of these tax measures would create a more neutral playground for the choice of exits which, to a large extent, is the crux of the matter.

Pierre Lortie is Senior Business Advisor at Dentons Canada LLP.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.