From: Rosalie Wyonch

To: Canadian drug regulators

Date: September 4, 2019

Subject: Drug Price Regulations and the Problem with External Referencing

Last month, the federal government released revised regulations for determining the maximum price of patented medicines in Canada. The new rules bring significant change to the way the Patented Medicine Pricing Review Board assesses whether or not the price of a patented medicine is “excessive.”

Some medicines will now be assessed for their cost effectiveness and total market impact. The new regulations will also evaluate prices net of rebates and discounts to insurers and distributors of patented medicines in addition to setting maximum (ex-factory) list prices. Previously, the PMPRB evaluated prices of new patented medicines by comparing to domestic prices of medicines in the same therapeutic class and the price in a set of comparator countries, labelled PMPRB7.

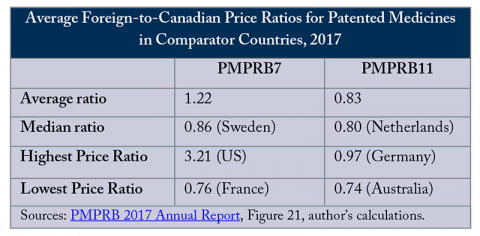

The new regulations change the countries used to compare prices: the United States and Switzerland – the only countries that pay higher prices for patented medicines than Canada – were removed and Norway, Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain and Japan were added, creating PMPRB11. This relatively minor administrative change is likely to have significant effects on prices and access to medicines in Canada and internationally.

Evaluating prices using the new basket of countries is likely to lead to significant price reductions in Canada. All countries in the PMPRB11 pay lower prices for patented medicines, on average, than Canada (see Figure). While the actual evaluations done by the PMPRB are complex and specific to the context of each new drug, comparing prices to more countries that generally pay lower prices for patented medicines than Canada, and removing the countries that pay more, will inevitably lead to lower price ceilings.

The problem with using international comparisons to regulate prices, or “external reference pricing,” is that it affects markets in comparator countries as well as domestically. Specifically, price regulation by external referencing, whereby high-price countries (in this case Canada) reference low-price countries, has indirect or spillover effects that contribute to launch delay and higher launch prices in low-price referenced countries.

Basically, Canada’s use of external referencing creates an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to seek higher prices or delay launch altogether in lower-priced reference countries to protect against the subsequent reduction in prices in the Canadian market. To achieve domestic discounts we are imposing negative welfare effects on other nations. Cost-effectiveness and market size evaluations do not impose these negative external effects.

Canadians should pay close attention to external referencing for another reason as well. In the not so distant future, we may become a lower-priced jurisdiction whose market is disrupted by becoming a benchmark for regulators and buyers elsewhere where prices are higher. Already, as of August 1, more than 270 bills have been filed in 47 US states to control prescription drug prices.

The size of the US market relative to Canada’s means that policy changes south of the border to regulate prices directly through the use of reference pricing or indirectly benchmarking prices to Canada by allowing importation, could have significant effects on the availability and price of pharmaceuticals in Canada.

New US policies, combined with the new, lower, price ceilings in Canada, may impede Canadian access new medicines if firms simply choose to delay drug launches in Canada to protect profits in the much larger US market.

Lowering drug prices is a priority for governments faced with unsustainably growing healthcare costs. The new PMPRB regulations will likely be effective at reducing domestic prices but come at the cost of imposing negative welfare effects on more countries. Moreover, if US states and/or federal programs implement policies to lower the prices they pay for patented medicines, the new rules may be too restrictive and result in the unintended consequence of delaying Canadians’ access to new and valuable medical treatments.

Rosalie Wyonch is a Policy Analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.