To: Fiscal conservatives

From: William B.P. Robson

Date: April 9, 2019

Re: Government deficits in Canada: The good, the bad, and the uncertain

Last month’s federal budget underlined the federal government’s abandonment of its commitment to return to surpluses. A critical test for any spending proposal – are we willing to pay for it? – does not figure in Ottawa’s thinking.

Defenders of federal borrowing like to point out that Canada’s overall public-sector balance sheet is okay. But dissipating national saving and increasing vulnerability to higher interest rates are either good or bad in their own right. If deficits are bad, excusing them on the grounds of better behaviour elsewhere is like a litterer pointing out that, since other people are tidier, there’s not that much garbage lying around.

Besides, not all other governments are committed to behave better. Some are in surplus and plan to stay there. Others are in deficit and plan to recover. But others, like Ottawa, are in deficit and plan to continue. And, with the 2019 budget cycle not yet finished, others are still question marks – including heavyweights Ontario and Alberta.

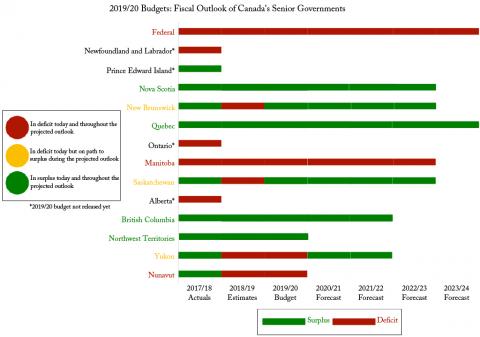

The federal government’s fiscal plan looks five years ahead, from the budget year, 2019/20, to 2023/24. As in 2017/18, the last year for which we have actual figures, and 2018/19, the year just ended, Ottawa shows red ink all the way (see figure).

Newfoundland and Labrador recorded a deficit in 2017/18: its budget later this spring will show whether it plans to get back to surplus. Prince Edward Island recorded a surplus in 2017/18: its budget will likely plan more of the same, but we do not yet know.

Nova Scotia, happily, shows continued surpluses through its four-year projection period. New Brunswick’s 2019 budget anticipated a deficit in the year just ended, but projected surpluses for the next four. These provinces face tougher demographic and program stresses than Ottawa, but are trying – and mostly succeeding – to cover their costs. The same is true for Quebec, which has been running surpluses, and plans more of the same through its five-year projection.

Ontario, like Newfoundland and Labrador, is a question mark. It has a big deficit, and the budget Thursday will reveal whether it has a plan to return to surplus.

Manitoba is also in deficit, and its four-year projection showed no surpluses, though its revenue and expense trends suggest it might get there in year five. Saskatchewan, like New Brunswick, anticipated a deficit in the year just ended, but plans surpluses for the next four.

Alberta will not deliver its 2019 budget until after its election later this month – at which point we will learn whether it has plans to bring its revenues and expenses in line any time soon.

British Columbia is in surplus, and its latest fiscal plan shows that it intends to stay there. The Northwest Territories only projects the budget year itself, for which it shows a surplus. Yukon is in deficit, with plans to get back to surplus next year. Nunavut is also in deficit – and, since it only projects the budget year itself, gives us no path back to balance.

In the figure below, with the assistance from Farah Omran, I provide a “traffic light” for Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial governments: green for surpluses, yellow for deficits with plans for surpluses, and red for ongoing deficits.

The budget laggards, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Ontario and Alberta, have still to report. If they project surpluses, they will make a key commitment to fiscal discipline, helping Canada’s public sector balance sheet, and setting an example that other governments – the feds most of all – should follow.

William B.P. Robson is President and CEO of the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.