The Study In Brief

Millions of workers in Ontario have no access to supplemental health and dental benefits that reimburse most costs for prescription drugs, dental, vision and mental health services. These services are indisputably essential to good health, productivity and financial security for workers and their families.

One solution is a portable health benefits (PHB) plan that allows a worker to maintain coverage while moving from job to job.

The Ontario government announced a Portable Benefits Advisory Panel in February 2022 with up to 18 months to advise on the viability, design and implementation of a PHB plan aimed at workers without benefits. This includes those who are self-employed, such as independent contractors, or in part-time, temporary or gig-type jobs.

This Commentary explores the purpose, structure and feasibility of a portable health and dental benefits plan in Ontario.

The author finds a PHB plan to be feasible, affordable and sustainable.

A portable plan is likely administratively feasible because private health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers and third-party administrators already use similar systems. A PHB plan can be integrated with new federal plans, existing employer-sponsored health plans and Ontario’s Trillium drug plan.

Participatory governance that includes workplace stakeholders should encourage public support and ensure ongoing innovation and sustainability. Provincial regulation will protect the public interest, similar to what Quebec requires for its universal drug plan.

Feasibility on many dimensions is critical. A key question is to what degree businesses must provide benefits. The government should anticipate resistance among small employers that do not currently provide a health benefit plan. Financial and fiscal feasibility depends on many variables, such as political will, eligibility, individual and employer mandates to take out insurance, and plan design including cost sharing. The best estimates are that 3.5 million to five million Ontario workers and their families would be eligible. Assuming an average annual per-capita claim cost of $907 (author’s estimate), the cost of this plan could be high: $3.2 billion to $4.5 billion, not including administration costs, tax considerations or subsidies for low-income workers, and assuming current provider service profiles and costs do not change.

However, this cost is likely to be shared by three parties – employers, workers and the provincial government. Cost would be reduced by Ontario’s share of previously announced federal spending on dental and mental health services, and by new federal funding for rare disease drugs. Assuming the province pays one-third of the new PHB plan claim costs, the annual provincial fiscal bill would be $1.1 billion to $1.5 billion. That would mean a PHB plan would consume between 1.5 to 2 percent of health program spending.

A PHB plan appears to be an appropriate way to improve access to essential health and dental benefits for millions of Ontarians.

The author thanks Benjamin Dachis, Rosalie Wyonch, Parisa Mahboubi, Alexandre Laurin, Art Babcock, Åke Blomqvist, Malcolm Hamilton, Zayna Khayat, Gavin Mosley, Liya Palagashvili, Marcel Saulnier, Paul Serafini, David Walker, Jennifer Zelmer and anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier draft. The author retains responsibility for any remaining errors and the views expressed.

Introduction

The workplace is changing, and millions of workers have no access to essential supplemental health and dental benefits that reimburse most costs for prescription drugs, dental, vision and mental health services.

These benefits are commonly tied to full-time, permanent and unionized jobs.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development

In February 2022, the government established a five-member Portable Benefits Advisory Committee.

The pandemic has underscored that need: one-fifth (22 percent) of Ontarians surveyed said they had no drug insurance in spring 2021, more than other surveys have reported (Statistics Canada, 2022b).

One solution is a portable health benefits (PHB) plan that allows a worker to maintain coverage while moving from job to job. PHB has never been planned or implemented anywhere in Canada, but there are American examples (online Appendix B). Federal initiatives toward a national pharmacare and near-universal dental plans also recognize these service gaps, as do billions of dollars

Before considering an Ontario PHB regime, there are many important issues that must first be addressed:

- What problem is this proposal aiming to solve or mitigate? Is a PHB plan necessary?

- What is the optimal scope of PHB program benefits?

- How should we ensure administrative, financial and political feasibility?

- Who are the beneficiaries, and which parties stand to lose?

- What will it cost, and how should those costs be shared?

- Are there better alternatives?

By addressing these questions, this report aims to inform those considering the need for, feasibility and value of a PHB plan, and to assist and augment Ontario’s Advisory Panel.

Overview

The major questions are whether to improve access to essential non-medicare health benefits and, if the answer is yes, whether a PHB plan is the best way to achieve this.

About 70 percent of Ontarians already have access to workplace health and dental benefit plans similar to what is being studied by the panel. Therefore, 30 percent do not. This is not equitable, although it is not a new situation. Clearly, there is significant unmet need for better access to health services. Consider:

- All Ontario residents have access to the provincial Trillium drug plan, which provides coverage for eligible prescription drug expenses that are high relative to household income. Still, a significant portion of the drug expense falls to the individual or family. A typical family with a 2020 median after-tax income of $79,500

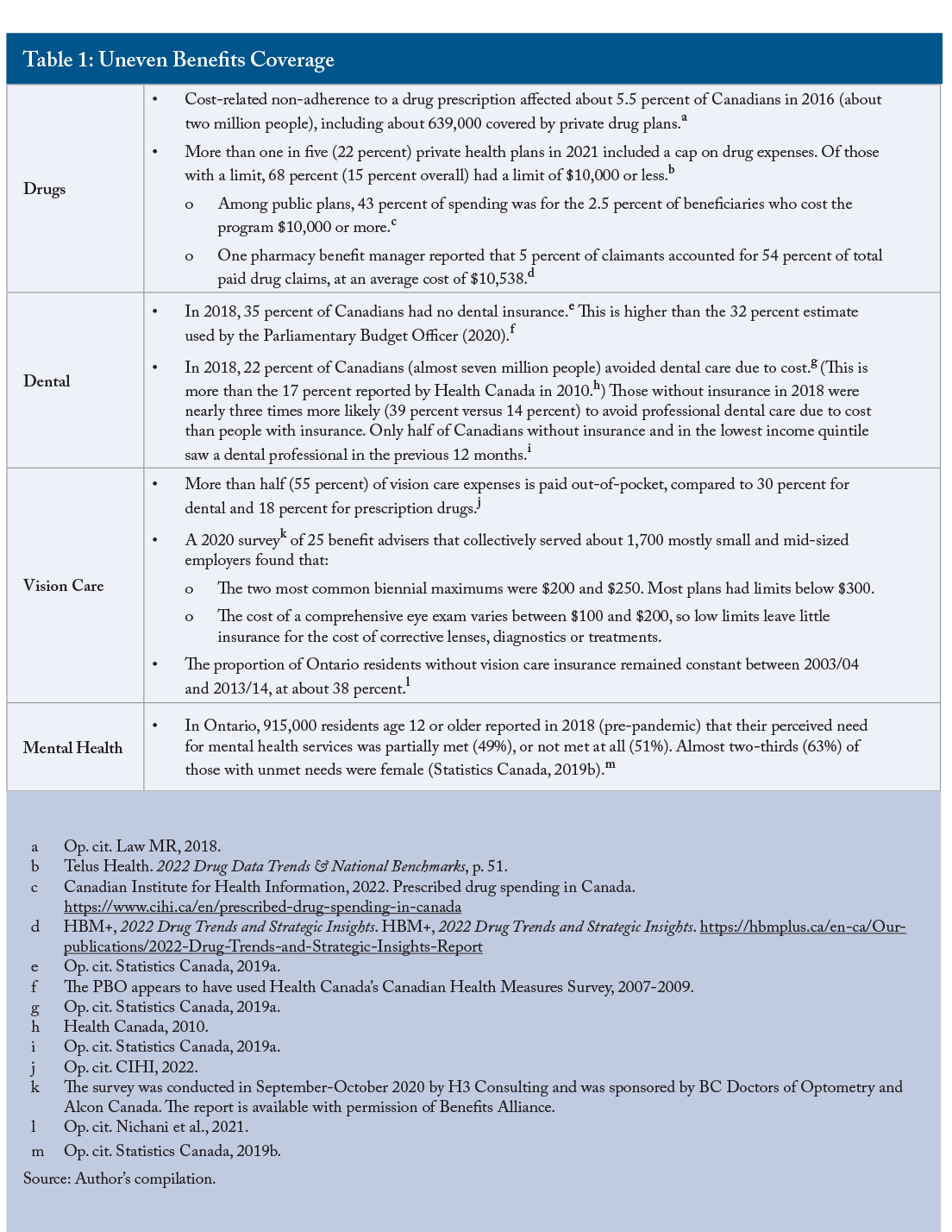

Statistics Canada, 2022. Household income statistics by household type: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions. Table 98-10-0057-13. See https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=9810005701&pickMe… Calculation: $79,500 x 0.04 = $3,180. had to spend at least $3,180 (4 percent of after-tax income) before triggering Trillium coverage.One reviewer suggested that PHB plan members could enrol in Trillium at the same time to improve efficiency for plan members and the government. Another option suggested is that PHB drug expenses could count toward the Trillium deductible, similar to the BC Pharmacare regime, although insurers may resist this on principle. - About two million Canadians (5.5 percent) reported they could not afford a prescribed drug (2016).

Law, M.R., 2018. - About 35 percent of Canadians had no dental insurance in 2018,

Statistics Canada, 2019a. leading to 30 percent of total costs being paid out-of-pocket.CIHI, 2022. Series A and H. Overall, 22 percent of Canadians reported avoiding dental care due to cost in 2018, increasing significantly to about 40 percent for those without insurance.Op. cit. Statistics Canada, 2019a. - More than half (55 percent) of vision care costs is paid out-of-pocket, so even those with insurance still likely have significant personal cost.

Op. cit. CIHI, 2022. Almost four in 10 (38 percent) Ontarians had no insurance for vision care.Nichani et al., 2021. - In Ontario, 915,000 residents age 12 or older reported in 2018 (pre-pandemic) that their need for mental health services was only partially met or not met at all. Almost two-thirds (63 percent) of those with unmet needs were female.

Statistics Canada, 2019b. Mental health worsened during the pandemic. - Diagnosis of a major depressive episode was associated with a significant reduction in earnings among Canadian adults, both in the year of diagnosis and during the next decade.

Dobson et al., 2021.

Based on the analysis that follows, a PHB plan is an appropriate way to improve access to health and dental benefits for millions of Ontarians. It appears to be feasible, affordable and sustainable. Participatory governance and management should help sustain public support.

A portable plan is likely administratively feasible because private health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers and third-party administrators (TPAs) already use similar systems.

Political feasibility must also be considered. Ontario is considering whether to create and presumably fund its own PHB plan, independent of the federal government. There is some indication of support across political parties for PHB plans, as evidenced by the Ontario Liberal Party’s 2022 Platform, (and within the British Columbia New Democratic Party’s 2020 Platform.) Party ideology may not be a factor.

Plan affordability depends on many variables, mostly unknown at this time, including political will, eligibility and plan design including cost sharing, discussed in Section 5. The best estimates of how many Ontarians would be eligible for a PHB plan range from 3.5 million to five million workers and their families,

However, this cost is likely to be shared by three parties – employers, workers and the provincial government. Cost would be reduced by Ontario’s share of previously announced federal spending on dental

There are important contextual considerations.

a) While a PHB plan may not receive much attention in itself, it may be positioned as an effective anti-poverty measure, or to lower the cost of living, or as a tactic that leads to more efficient and equitable administration of existing health and social services.

b) Access to health benefits may help prevent or mitigate acute and chronic illness or injury, leading to greater workforce participation and mobility as well as higher provincial tax revenue.

c) A PHB plan may provide an opportunity to broaden and improve governance by including workplace stakeholders such as employers, insurers, unions, workers and healthcare providers. This collaboration could improve strategy, provide richer insights on costs and benefits, and share responsibility for results.

d) A portable plan with mixed and coordinated funding and governance could reduce the incentive for cost shifting between provincial and private health plans.

e) Better data systems and more consistent oversight should improve member navigation of services delivered by public and private insurers.

f) Assuming a PHB plan is privately administered, plan members would have access to multilingual service delivered across multiple platforms (e.g., telephone, web, app and chat) that provincial health plans do not offer.

g) Employer behaviour is important to anticipate and monitor. There are two facets to this concern. First, if employers can pay less and carve out or terminate existing health coverage, many will take advantage of a PHB plan. Second, some employers that have chosen not to provide health benefits can be expected to strenuously resist any requirement for a financial contribution. Exemptions and incentives are needed to prevent or mitigate these risks.

h) Greater risk spread makes health costs more predictable. A PHB plan administered by private insurers could deepen the risk-sharing pool already in place for small group health benefit plans.

i) Pooling PHB plan enrolment with either private or provincial health plans could improve scale, reduce administrative costs and mitigate the increases in provider costs over time.

j) A provincially sponsored PHB plan might be able to access lower drug prices from the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance.

Based on an initial review, there do not appear to be any better alternatives to a PHB plan if the government wants to improve access to targeted health services. The main advantages to a PHB plan are stable and high-quality benefits to workers in non-standard employment with shared costs and, potentially, governance to mitigate affordability and sustainability concerns for government, employers or workers.

The main limitation noted in this report is that introducing a new health plan will be a very contentious issue. This current estimate of the scope, eligibility, cost and cost-sharing of a PHB plan suffers from inadequate data and the need for many assumptions.

A number of recommendations are developed and discussed in this report.

- After investigating essential plan design, eligibility, costs and cost sharing, a PHB plan appears to be a feasible approach to extending insurance for essential health services to working Ontarians and their families. As with OHIP+, Ontario’s drug plan for those under 24 not otherwise covered, PHB coverage would be reserved for residents without access to an employer- or association-sponsored health plan.

- As a foundation for a PHB plan, social health insurance principles should be followed, including regulation of insurers for plan design, out-of-pocket costs and risk sharing. These principles also include an individual mandate to have coverage that is at least equal to the regulated standard.

- PHB governance should come from a board of directors that is granted sufficient authority and includes key stakeholders such as employers, insurers, unions, workers and healthcare providers.

- Carefully define individual eligibility for PHB, with particular attention paid to employment status and consistency across Ontario labour laws.

- Assuming insurer administration, consider comingling claims from PHB and group health plans to enhance existing individual drug claim pooling and industry risk sharing.

- Ensure a broad contribution base with approximately equal funding by employers, workers and governments. PHB plan funds should be kept separate from group insurance and general taxes to enhance transparency, encourage competition and extend the list of services. Due to the broad scope of Ontario’s contemplated PHB plan, and for administrative simplicity, customers of selected services, such as taxi, ride sharing or hospitality, should not be a separate source of funding.

- Ensure that tax treatment of PHB plans for both employers and workers is equivalent to what is provided through the Income Tax Act’s treatment of private health services plans. This includes employer deductibility of PHB contributions and that PHB benefits are tax free to workers. Incentives to continue existing employer health plans are needed to avoid the unintended consequence of shifting huge costs to the government.

- Controlling costs overall and for the government is important, as is retaining equity among payers. To avoid having employers terminate or reduce existing health coverage, government regulation should discourage, restrict or prohibit this unintended consequence.

This holds unless it is the government’s intent to replace all group and association plans in the province. An employer mandate to provide coverage at least as generous as offered by the PHB plan may be required, although this will be highly contentious in some employer segments. There are three offsetting arguments: First, about half of small employers already provide health benefits; The additional cost for those who may be mandated to offer a PHB plan is unlikely to be onerous; and Employers, given current skills shortages, are more likely to accept a PHB plan or improve health coverage to boost employee satisfaction and loyalty and to help recruit workers. Resistance can also be mitigated through exemptions for small businesses with fewer than 10 employees or those in their first year or two of operation. - Develop a PHB plan with coverage scope and quality that compares well with existing employer-sponsored health benefit plans. Employers should be able to provide their workers with additional benefits or greater subsidies.

- It is uncertain how many Ontarians will still be excluded, but their needs for similar health coverage should be considered.

- Premium subsidies and exemptions should be provided to low-income workers.

- Operate a PHB plan as a pilot for the first year or two and phase in enrolment with rigorous expert evaluation of need, process and outcomes.

- Ensure that PHB program managers and governors regularly monitor plan administration, features, benefit levels and enrolment to ensure optimal reach, efficiency and member satisfaction; e.g., through online, virtual and self-help preventive services, and stakeholder consultation.

- Anticipate federally led pan-Canadian dental and drug (i.e., national formulary and rare disease drug strategy) plans and integrate a provincial PHB plan with them.

- Determine if a PHB plan can take advantage of pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance drug pricing.

- Ensure all healthcare providers are paid an adequate fee for their services.

- Ensure coordination with private health services plans and provincial benefits to reflect and support the employment mobility of the targeted PHB demographic.

- Undertake administrative scenario planning and consider transitions in and out of a PHB plan, such as:

- If a worker with PHB coverage becomes eligible for a better group plan through a new employer;

- If an employed worker becomes self-employed, which party pays the employer share?; or

- Whether OHIP and OHIP+ eligibility can be harmonized with PHB benefits for new residents.

Meanwhile, it is critical to ensure that any waiting period for PHB plans is minimal. Eligibility should occur no later than the first of the month following enrolment.

It is strongly recommended and assumed that further investigation will be undertaken to validate the number of eligible Ontarians, the scope of benefits along with costs and cost-sharing. These variables are central to determining the practical feasibility of a PHB plan.

Setting the Stage

1. Portable Health Benefits (PHB) Defined

Portable benefits may include any or all of several health, disability and retirement supports that are attached to a worker rather than sponsored by a specific employer. They are not publicly funded and administered, although they may be government subsidized. A well-known example is the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) to which employers and employees contribute over decades to provide not only a guaranteed pension but potentially other more immediate benefits such as income replacement payments to disabled workers. All contributions from all sources over a full career are vested with and follow the worker. The closest fully private example is trusteed health and pension benefit plans

The Problem

The lack of health and other benefits for millions of Ontario workers in non-standard employment is a societal failure that needs addressing. Non-standard employment is defined as those who are self-employed, including independent contractors, or in part-time, temporary or gig-type jobs. While the percentage of these workers has been steady in all but gig employment, absolute numbers have increased with growth in population and the labour force.

Low-pay work and job classification are also related to access to health benefits. One in five employees (20 percent) earned less than the low-pay threshold of $17.33 per hour in 2021. Low pay is also associated with non-standard employment and is more common among women, part-time employees and employees aged 15-to-24 years.

The federal government has begun to implement a national dental plan, but a permanent plan is not expected until 2025. National drug insurance (“pharmacare”) is currently limited to narrow tactics such as a rare disease drug strategy and development of a national formulary, but pharmacare legislation is expected in 2023.

Rationale

A PHB model that supplements medicare would be novel in Canada but could potentially improve the health, social and financial security of workers. Tying benefits to the worker instead of to an employer would improve labour market mobility. Depending on the design, funding and administration, the added cost may be manageable for smaller employers that do not currently provide health benefits because PHB plan costs would be shared with workers and governments.

History

Access to PHBs is not a new issue. Several government, academic and industry studies acknowledge changes in the workplace and the need for new approaches to enhance job quality and security in Ontario, including access to health benefits.

- Lankin and Sheikh (2012) recommended that “prescription drugs, dental, and other health benefits [become] available to all low-income Ontarians” (p. 79).

- Lewchuk et al. (2013) wanted employer-type health benefits extended to all those in precarious work (p. 99).

- Johal and Thirgood (2016) specifically called for a PHB plan for gig workers (p. 48).

- Busby (2020) recommended the federal government develop and pay for mandatory private health insurance for any Canadian not enrolled in a public or private health plan.

Benefit Scope

The scope of the Ontario PHB initiative is expected to cover supplementary health, vision and dental coverage, with perhaps extra support for mental health needs. Absent any detail to date, it is assumed coverage quality will be mid-range relative to current group benefit plans.

Another important gap in the social safety net is income replacement for occupational or non-occupational illness and injury suffered by workers who are excluded from Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, CPP Disability or Employment Insurance sickness benefits. At this time, it is assumed that income replacement is not part of the initial design.

Principles

Like employer-sponsored or trusteed health plans, a PHB plan would supplement or complement provincial health plans. Principles are essential to consistently and fairly govern program goals, processes and decisions, and to ensure accountability. Some consistency should be considered, given multiple parties involved in funding and delivery. Two public plan examples of relevant principles follow.

The Canada Health Act (1984) includes five well-known principles

In 2022, an advisory panel sponsored by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH 2022) proposed six principles for a new pan-Canadian drug formulary:

- Universal and integrated;

- Equitable;

- Effective, safe and high quality;

- Sustainable;

- Efficient and timely; and

- Inclusive and transparent, with fair process.

On the assumption that a PHB plan requires the cooperation and support of several parties to administer, fund and report on worker entitlements, an ethical and consistent approach is necessary. The CADTH list appears to be more appropriate for a single-province plan that will almost certainly include private payers.

Beneficiaries

Who is eligible has a huge effect on how much a PHB plan will cost. The Ontario government’s portable benefits announcement envisioned that eligibility be: “workers who fall outside of traditional employer provided benefits,” most likely those without health and dental plans. This report assumes their family members will also be included.

The number of potential beneficiaries (3.5 million to five million) is discussed in Section 5.

Where Private Health Benefits Fit In

A robust supplementary private health benefit market has existed in Canada since the 1970s. More than 10 million Ontarians have access to workplace, association or individual health plans, though coverage quality is highly variable. The role of private insurance is one of the most important questions related to health insurance – and a flashpoint for controversy. Beyond identifying the purpose and scope of private health benefit plans is the need to ensure close coordination among provincial, existing private and new PHB plans.

The private payer community includes insurers and employers but also advisers, pharmacy benefit managers and TPAs.

It is important to note that employers, not insurers, pay for health benefit plans and very often carry most or all the financial risk.

In planning a PHB program, the province will need to recognize that employers have different goals and priorities for their health plans than governments do for public plans. One national survey of 553 employers reported that their top three reasons for providing a health benefit plan are to:

- Attract and retain employees (21 percent);

- Prevent undue financial burden for employees (17 percent); and

- Keep employees healthy and productive (16 percent).

Benefits Canada Healthcare Survey, p. 26.

The scope and quality of private plans has not been fully or rigorously assessed. However, large, national surveys of plan members show generally high satisfaction with coverage, with lower satisfaction reported by those with low incomes or in poor health. Like provincial plans, coverage can vary significantly, with different eligibility, scope, co-pays and annual or lifetime limits.

The Best of Both Worlds

It is the combination of health funding and delivery from both sources that allows Canadians with private plans to have health coverage that approaches what is available in other countries with broader universal public health systems. Absent private health plans, personal cost and affordability can become a problem, especially when those costs are high relative to family income.

Despite ongoing ideological debate, a health system doesn’t have to be either private or public. In fact, OECD members typically have hybrid health systems with public, private and social insurance delivery and funding.

A PHB plan could use or adapt the best technology from both payers. Technology illustrates a complementary approach. Health technology assessment used by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) and Quebec’s Institute national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS) for federal, provincial and territorial government health plans is currently superior to that used by most private insurers.

2. Needs Assessment: Core Problems

Interest Drivers in a Portable Health Plan

Three main concerns drive interest in PHB plans. The first and most commonly cited is ongoing change in the nature of work and employment. As a consequence, workers in non-standard employment rarely have access to supplemental health benefits. The third driver is the limited eligibility and scope of medicare services, especially for those of working age.

Shifting Nature of Work

Permanent, full-time employees have typically enjoyed a variety of statutory and voluntary benefits, but these are far less likely among other classes of employment such as independent contractors. Increased automation, misclassification of work, precarious and on-demand (“gig”) employment combined with limited private sector unionization

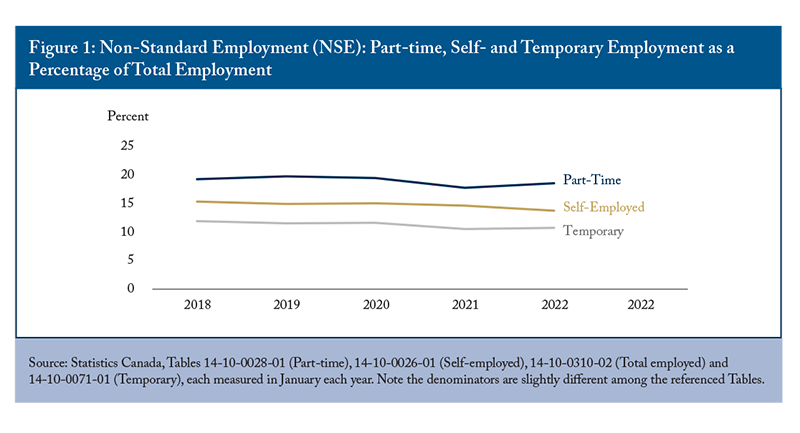

Mitchell and Murray (2017) cite Ontario Ministry of Finance estimates in concluding that almost 27 percent of Ontario workers were in non-standard employment in 2015. Over the last five years, such employment – when described as part-time, self-employed or temporary – has remained fairly steady overall and as a share of total employment (Figure 1), even through the pandemic. From 2018 to 2022, total employment increased by 4 percent in absolute numbers, and full-time employment increased almost 5 percent. However, while the number of part-timers remained virtually the same during this period, self-employment was down more than 6 percent, and temporary employment was 5 percent lower.

The Quality of Employment Survey (Statistics Canada 2022c) reported that workplace health benefit coverage was more likely for permanent employees (68 percent) than fixed-term contract employees (39 percent), self-employed persons with employees (28 percent) or without employees (7 percent), and other temporary employees (14 percent). Note that full-time employment may be permanent or temporary.

Job status is a proxy for access to health benefits. While these traditionally labelled classes have been essentially stable, the number of workers without access to health and dental benefits remains significant, and a new class of independent gig workers needs special consideration.

Gig Workers – A Special Case?

Growth in the gig economy often drives discussion of the need to broaden access to supplemental health and dental benefits. The latest study data, now somewhat dated (Jeon et al. 2019), reported that the share of gig workers in the labour force grew from 5.5 percent in 2005 to 8.2 percent in 2016.

- Slightly more than half of gig workers earned money from another job. Supplementing pay is essential since the median net annual income from gig work was just $4,303 in 2016.

- Gig workers were twice as likely to be in the bottom 40 percent of earners as non-gig workers, were more likely to be female, immigrants in Canada for fewer than five years, and working in arts, entertainment and recreational jobs.

- While about half of gig workers have no gig income the following year, about one-quarter remains in gig employment for three or more years.

An unknown number of gig and low-pay workers likely have access to health benefits through a spouse or parent. Many gig and low-pay workers may be unable to financially share in the cost of a PHB plan, so subsidies and cost waivers should be considered.

Uneven Access to Different Health Benefits

Private health and dental plans do not all have the same quality or scope of coverage. So, while more than 60 percent of Canadians are enrolled in a plan, each component needs to be independently assessed (Table 1).

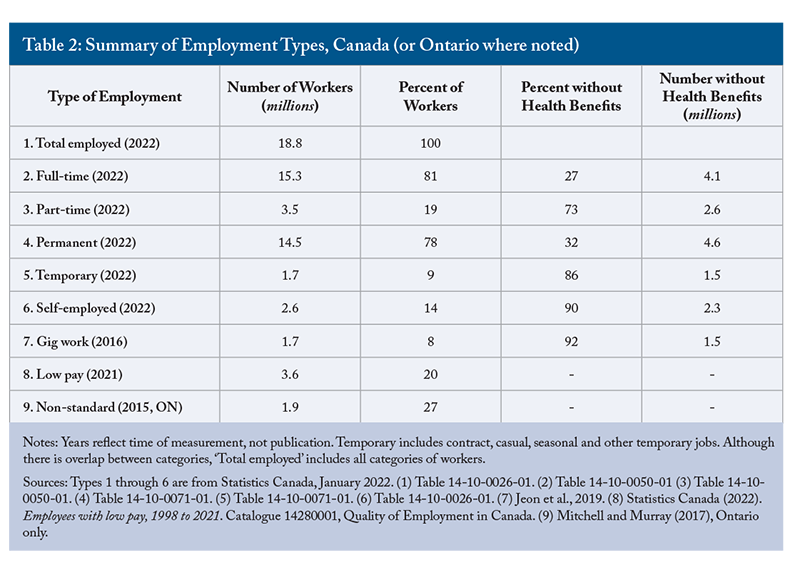

Summary of Employment Types

Relevant job categories are listed and the number and percent of workers are shown in Table 2.

There is no single metric that can accurately define the group of workers who may be eligible for PHB by type of employment, or how many of them do not have access to health benefits. The number of workers with any access to public drug and dental benefits is unknown. Specific and accurate data do not appear to be readily available, yet are crucial to determining who will benefit and how much a PHB plan will cost.

Medicare

Canada’s medicare can be described as deep but very narrow relative to other OECD countries. Hospital and physician care now account for just 38 percent of total health spending (CIHI 2022), compared to 57 percent in 1984 when the Canada Health Act was enacted.

Despite many attempts since the end of the Second World War, we have yet to include consistent, universal access to prescription drugs. Dental was a peripheral issue, at best, until the March 2022 Confidence and Supply Agreement between the federal Liberals and NDP suddenly brought it to the fore. Meanwhile, many essential health products and services are not publicly funded, depending on age, province of residence, access to private insurance and health status. These include drugs, dental, vision care and physical and mental therapy.

While none of these sources provide identical data or insights, it is clear that even the combination of private and provincial health insurance leaves significant cohorts of Canadians without access to essential health services.

3. Portable Benefits in Canada and the United States

Canada

Ontario public drug, dental and vision care plans are provided to specific populations such as seniors, children, social assistance recipients, patients in palliative care or residents with specified chronic conditions like cancer or cystic fibrosis. Notionally, these plans follow the individual, but are all tax-financed, entitlement-based programs and many exclude working-age residents. Drug plans are sometimes coordinated with private health plans, but the order of payment varies by province.

Quebec provides a compulsory, public drug plan that uses the provincial formulary if a person has no employer coverage. Drug coverage is, therefore, universal, but can also be considered portable within Quebec, since all residents have access to a certain minimum standard of protection. Quebec also provides dental services to all children up to age 9.

Eight provinces offer protection from drug costs that are high relative to family income, although the threshold varies significantly. Uniquely, Alberta and New Brunswick offer voluntary, premium-based drug plans to all their residents, including workers, with coverage based on the provincial formulary. Blue Cross administers these plans on behalf of both provinces.

Relevant to PHB plans, Saskatchewan provides an annual comprehensive eye examination to all children up to age 17 and in cases of ocular emergencies.

Health and Welfare Trusts

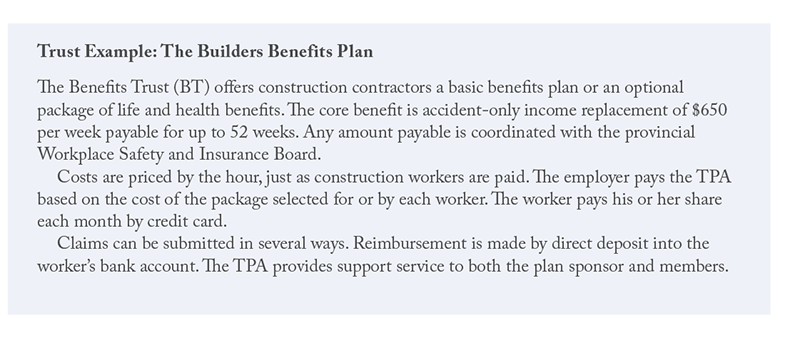

In the workplace setting, multi-employer trusteed health and pension plans follow the worker, who is usually a union member. These plans provide a long-term, real-life model of how supplemental portable health benefits are provided to private sector workers in non-standard employment.

Trusts exist in both Canada and the US and are similar to employer-sponsored plans. Trusteed plans involve multiple employers. In most cases, a labour union negotiates compensation including health benefits on behalf of its members in a defined geographic area or a particular trade (e.g., pipefitters, construction, firefighters) or profession (e.g., the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists and the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada). The plans are jointly governed by management and labour representatives.

Entitlements and benefits are attached to the worker, and contributions are usually paid by an employer to a TPA or insurer based on the hours worked by that worker. The TPA then submits life and disability premiums to an insurer, manages enrolment changes and often pays the health or dental benefit to the worker according to the contract. Independent, non-union contractors are ineligible.

Insurers such as Canada Life and Manulife, as well as Green Shield and Blue Cross, currently provide different types and levels of PHB plans as individual or association plans or if a worker loses their job or their benefits coverage. However, these plans are expensive relative to group plans, and health and dental benefits are much more limited. Individual plans are medically underwritten and pre-existing health conditions may be excluded, or the insurer may refuse all coverage.

United States

The American market has several relevant examples of portable health, retirement and workers’ compensation benefit plans. Since 2015, several reports have been published by the Aspen Institute under their Future of Work Initiative. The most recent “Roadmap” report (Gervais et al., 2021) examines where to start and how to implement a universal portable benefit in the US.

Details of a sample of American portable health and retirement plans are included in online Appendix B. Key points and their sources relevant to policy and program development in Canada are noted below.

- Plans may be developed for specific occupations (Black Car Fund; NDWA-Handy Pilot) or locations (Black Car Fund in New York State) or sectors (not-for-profit in Massachusetts).

- Benefit types and levels may be negotiated between management and organized labour groups (Black Car Fund, NDWA-Handy Pilot).

- Enrolment by workers may be voluntary, but their employer must be registered (Black Car Fund).

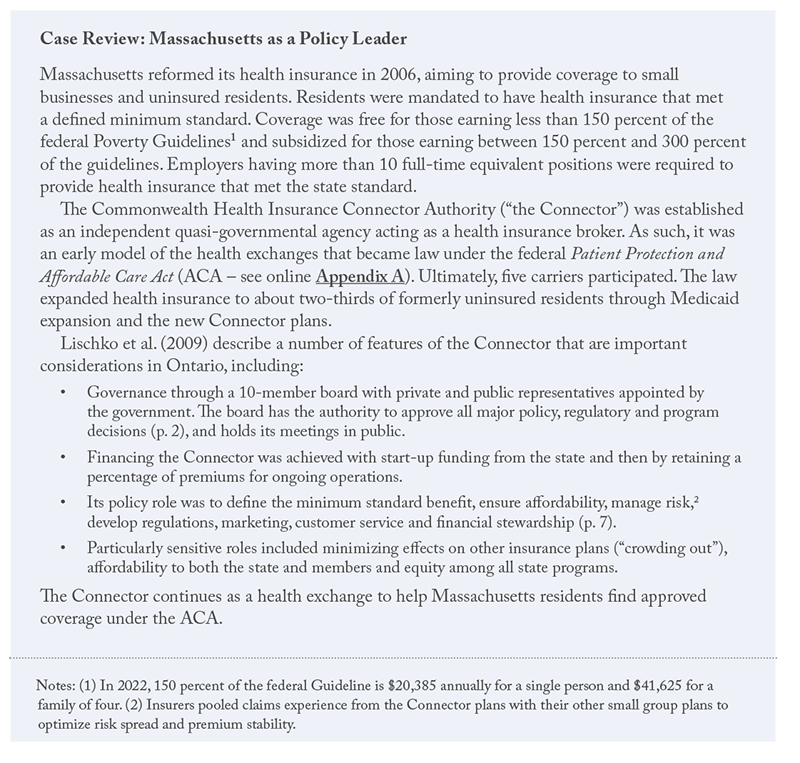

- State-sponsored health plans usually mandate residents to join and provide a minimum standard of coverage (MA, WA).

- Three cities (San Francisco, Seattle and Philadelphia) sponsor their own portable plans.

- Costs are most often shared among governments, employers and members. If an employer refused to join, Tennessee allowed workers to enrol if they paid both their own and the employer’s share. The Black Car Fund includes a mandatory customer surcharge of 3 percent of the ride cost to fund all benefits.

- Health coverage may be free or subsidized for low-income residents (MA).

- Some states mandate employer enrolment in Secure Choice portable retirement plans according to employer size, starting with the largest employers and progressing over time to small workplaces (IL, CA). New York aimed immediately at small employers, those with at least 10 full-time equivalents. Employers that have their own plan are exempted. In Illinois, employers were exempted until they had operated for two years.

- Sometimes, individuals (IL) or the self-employed (IL, CA) may join.

- Competition among insurers was a design feature in MA and TN.

Design Considerations

4. The Preferred Model – Social Health Insurance (SHI)

A social health insurance (SHI) model provides a legal and practical foundation for a PHB plan. While SHI normally supports a universal system (Europe) or program (Quebec), it can also be adapted to provide a PHB plan for a specific population cohort; i.e., workers.

SHI Overview

Two major models for health insurance operate globally. The first is a public single-payer plan, evidenced in Canada by our deep but narrow universal coverage of hospital and physician services that are essentially free at the point of delivery.

The second model is social insurance which originated in Germany 140 years ago and underpins the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, Workers’ Compensation Boards across Canada and drug insurance in Quebec. Many characteristics are the same or similar between the two models; e.g., universality, but there are differences. For example, public single-payer plans are largely funded by general tax revenues, while social insurance has mixed financing.

SHI would formalize the existing structure, institutions and processes already involved in financing and delivering medical and dental insurance. It does not require governments, often heavily indebted, to independently finance health programs.

SHI systems operating in several countries include other key features and attributes.

- Insurers are regulated to meet their social responsibility and provide minimum standards for plan design quality and out-of-pocket cost, as well as a level of integration with public coverage; e.g., Quebec’s universal drug plan (see Regulation). In most countries, employers must provide a plan that meets legislated standards.

- When there are competing insurers, beneficiaries may change insurers annually to encourage competitive plan design, pricing and steady innovation.

- Coverage is mandatory and, therefore, universal to ensure broad risk spread and sustainable funding. All residents or citizens are covered regardless of individual risk.

- Premiums and/or taxes are eliminated or subsidized for low-income beneficiaries, or perhaps those with specified chronic diseases and comorbidities. Studies in many countries, including Canada, conclude that incomes and health status are positively correlated.

- Financial subsidies and the plan’s benefits serve to redistribute health

Health-risk redistribution occurs because subsidized cost makes health services more available and equitably distributed. Cost-related non-adherence to drug therapy illustrates inequitable care based on wealth and subsequently leads to lower health status. Over time, redistributing heath risks results in less disparity between risk cohorts. This situation occurs in all health systems, whether public single-payer or SHI. and wealth to less healthy and lower-income individuals. - Mixed funding is provided primarily by employers and members, with additional contributions by governments to reinforce coverage as a social good and to keep contributions by the other two parties affordable over time. The government contribution also recognizes the participation of children and others not in the workforce.

- SHI contributions are paid into a dedicated fund, like Quebec’s Drug Insurance Fund, which improves transparency and program evaluation.

- Costs are covered either by premiums or taxes. The two financing mechanisms are not discreet but exist on a continuum, which again provides Ontario with choice. It should be noted that many workers are not in a payroll system, so while payroll taxes make sense for traditional business structures, SHI worker contributions are managed by the plan administrator and some costs may be collected retroactively through the income tax system. The cost to employers and workers for a PHB plan must be compared to a similar suite of benefits now provided through employer-sponsored group plans.

There is reason to think a PHB plan could cost less than a comparable group plan by considering how to reduce or eliminate premium and sales taxes as well as certain administrative and sales costs. Using pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance drug prices may help, and lower fees may be negotiated with providers. However, care must be taken to not unduly disrupt the existing group market or a significant share of it could migrate to a publicly subsidized PHB plan. - Administration is usually provided by a not-for-profit organization at arms length from the government. An alternative approach in Ontario could be a competitive bidding process with the winner(s) awarded multi-year contracts. Electronic claim submission, invoicing and payments are already available to many healthcare providers.

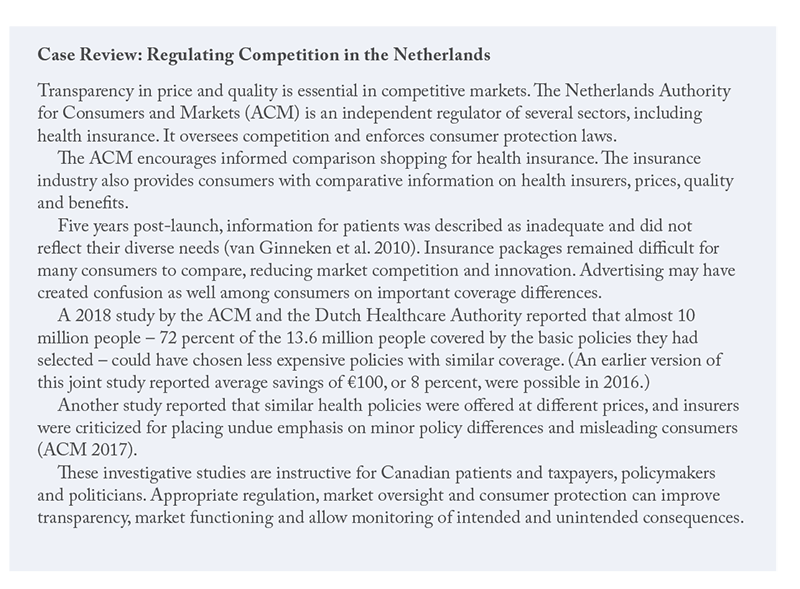

- Competition should encourage insurers to innovate, provide products that meet diverse and evolving member needs, improve efficiency and ensure good value. Competition varies and has significant regulatory oversight in most European countries (see Box: Case Review: Regulating Competition in the Netherlands).

Although SHI is widely used in Europe and elsewhere, no two countries have the same system. Features and attributes vary according to legislation, institutions, financing and history. In fact, various studies report there are likely no pure examples of either the public single-payer or SHI system. Health systems do and ought to evolve. SHI can be adapted to suit stakeholder needs in Ontario, and is well-suited to a portable health benefits plan.

Governance

Governance of publicly funded health services in Canada typically resides with Ministries of Health and/or Social Services, with medical associations often exerting a strong influence. An Ontario PHB plan presents an opportunity to have a more participatory governance model that includes key stakeholders such as workers, employers, health professionals and other experts, as well as the provincial government. Wider expertise improves the breadth and depth of insights needed for plan governance in a complex, complicated and rapidly evolving health and social environment. Political accountability can be retained.

In Germany, the multi-stakeholder Federal Joint Committee

Administrative Feasibility

While the need for access to supplemental health benefits is clear, the solution must be feasible in terms of process (i.e., design, administration and financing) and outcomes. A PHB regime is complex, so it should be introduced in phases. A pilot project using one or more selected population cohort(s) can test need, process and outcomes.

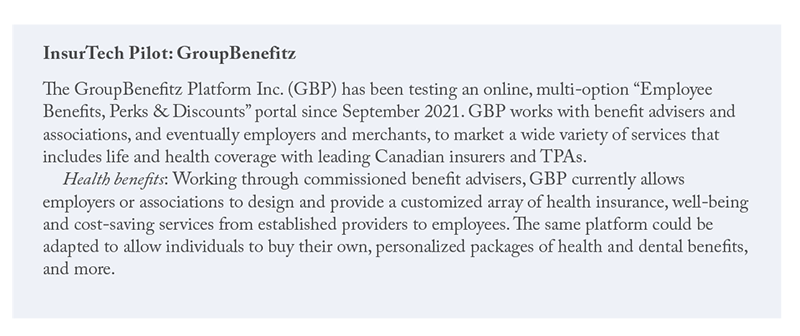

About half of small employers don’t provide health benefits, and concern over difficult or time-consuming administration may be an important deterrent. In response, at least one simplified online benefits administration platform is already being piloted (see: Box on InsurTech Pilot: GroupBenefitz).

The OHIP+ experience indicates that planning and implementing PHB is not a trivial undertaking. Many stakeholders must be not only consulted but actively engaged in the design, planning, transition and administration roles. The list would include representatives of workers currently excluded from benefit plans, as well as insurers, employers, health professionals, potential administrators, the federal government and, internally, from among several ministries.

Gig workers, independent contractors and the self-employed may need additional consideration relative to part-time, contract or casual workers who are hired by just one employer. However, TPAs and insurers already serve trusteed plans, and the core structure and processes are consistent with a SHI system.

5. Finance: Model Parameters and Estimates

The provincial government has initially identified financing sources as “consumers, employers, workers and the government.” The advisory panel is to consider costs to ensure that employers are “able to remain economically competitive.”

PHB plan costs depend on many parameters:

- The scope of benefits. A working assumption is that benefit levels will be mid-range relative to current offerings in the group insurance market.

The term “mid-range” is subjective at this time, but meant to convey a good-quality group plan. Similar to federal drug and dental proposals, the Ontario government’s approach may leave room for private insurers to provide top-up or expanded coverage beyond a mandated level. - The number of eligible beneficiaries and their health needs, as well as the cost of subsidies and exemptions.

- Whether employers will choose or be required to continue health plans already in place.

- The degree of choice offered in plan design, including access to optional top-up benefits.

- Cost-sharing among the workplace parties and/or consumers, which could include premiums and/or a dedicated payroll or other business or consumer taxes.

- The time and cost to create or modify existing administrative systems to track eligibility, enrolment, use and payments, and to hire and train staff to serve millions more members.

- The degree of regulation borne by different parties regarding, for example, individual and employer participation mandates, annual reporting or a governance structure.

- The financial exemptions available to employers that provide benefits to all employees that exceed the minimum standards of the PHB plan.

Mitigations to be considered for employers might be modelled after:

a) Ontario’s employer health tax: Employer contributions are scaled by size.

b) Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act: Exempting the smallest (or newest) businesses from contributions or from meeting certain requirements.

c) Employment Insurance premium reduction for qualified weekly indemnity plans.

d) Tax and expense deductibility for private health services plans under the Income Tax Act.

Coverage Estimates

The number of Ontarians potentially eligible for portable health benefits has a profound impact on cost estimates.

There are several estimates of the number of Canadian workers or residents, less frequently specific to Ontario, who don’t have access to health and dental benefits (online Appendix C). Many of these reports are older, incomplete and not specifically done for a PHB plan. In general, better data are needed.

Among those reports, there are two high-quality estimates originally from Statistics Canada of the number of workers and/or family members who have access to employment-related health and dental plans. Each has different sampling, time frames, adjustments and limitations.

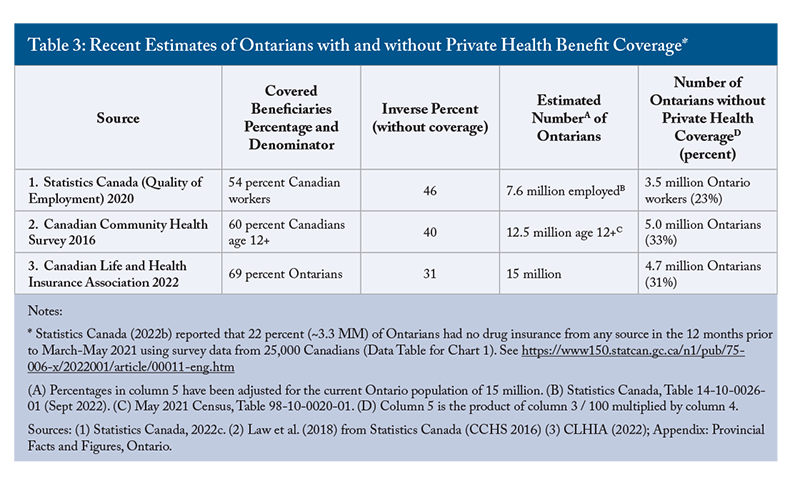

In addition, the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association provides annual estimates of the number of Canadians with private health coverage, but its methodology is not public. The association estimated that 69 percent of Ontarians had extended health coverage in 2021, mostly through employment. Table 3 provides a summary of coverage estimates within these three sources.

In Ontario, private health premiums are split 92 percent workplace or association (group) plans and 8 percent individual.

Range Estimates and Confidence

These three sources suggest that 3.5 million to five million Ontarians (23 percent to 33 percent) do not have private health plans and may benefit from a PHB plan. Other studies (online Appendix C) indicate 18 percent to 50 percent of Canadians or Ontarians do not have private health plans.

No useful data could be found to identify how many Ontarians are currently eligible for Ontario Public Drug Plan (OPDP) benefits.

The age, quality, potential for bias and the wide range of estimates reduces overall confidence in this range.

Available data also do not reveal what benefits (e.g., drugs, dental, vision) are included in survey responses about employer-sponsored or workplace plans. Another important factor – the quality of those benefits – is not assessed or reported

Financial Model Parameters

Financial models must include appropriate and transparent assumptions to ensure a new plan is affordable to all parties. Sustainability should be regularly assessed, perhaps every five years.

The number of eligible Ontarians, the scope of benefits, costs and cost sharing and the role of coverage mandates for individuals and/or employers needs further investigation. These variables are central to determining the practical and ongoing feasibility of a PHB plan.

Here, I propose a number of assumptions for a costing model:

- Studies (online Appendix C) report a wide range in the number of eligible Ontarians without workplace health benefits. Poor data preclude a valid and reliable estimate of the number with public coverage or the number having both private and provincial coverage such as seniors or Trillium beneficiaries. The best estimate is that 3.5 million to five million Ontarians may be eligible for a PHB plan.

The final number will be adjusted for cohorts already partially covered by Ontario under Trillium, OHIP+, ODSP or OW. - The Canadian Institute for Health Information (2022, Table A.3.2.3) forecast that average annual per-capita private spending in 2022 would be $451 for dental, $565 for prescription drugs, $183 for other professionals and $154 for vision care. The total cost for these four types is $1,353.

As an alternate source, Canada Life reported average drug and dental claims per certificate (employee and all dependents) of $1,270 for prescription drugs and $1,173 for dental in 2022 (Conference presentation, Barb Martinez, Canada Life, February 14, 2023). Using the 2021 Census average household size of 2.4 persons, these averages convert to $489 per capita for dental and $529 for drugs. Their sum ( $1,018) is almost identical to what CIHI forecast ($1,016) for these expense types. Assuming a new PHB plan provides mid-level coverage, the average cost per beneficiary might be 67 percent of the total, or $907. Many variables and assumptions affect these costs. A median cost may be lower due to skewing of the cost distribution. PHB plan members are assumed to be ineligible for any other workplace plan or significant provincial benefit.As plan design and cost sharing are further developed, an appropriate contingency margin should be included. - Gross claim cost, before coinsurance, would, therefore, be $907 million in year one, per million beneficiaries. For 3.5 million to five million beneficiaries, the cost of claims is estimated at between $3.2 billion and $4.5 billion. Funding should be shared among the government, employers and workers. Including consumers of selected services such as taxi, ride-sharing or hospitality as funders is not recommended because of the broad scope of Ontario’s contemplated PHB plan, as well as for administrative simplicity.

- Assuming the government pays a one-third share, new government spending for the PHB program would be $1.1 billion to $1.5 billion in year one. All else held constant, costs would be higher in the first year due to pent-up demand and will increase every year. For reference, Ontario Ministry of Health spending is projected at $75.2 billion for 2022/23 (Chart 3.5 p. 196).

Government of Ontario. https://budget.ontario.ca/2022/pdf/2022-ontario-budget-en.pdf - Administration costs are assumed to be 3 percent of paid claims,

The federally financed Non-Insured Health Benefits plan cost $18.47 million for claims administration in 2017/18, or 1.4 percent of paid benefits of $1.31 billion. See Figures 3.2 and 9.1 at https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1581294869253/1581294905909 or $95 million to $135 million in year one. There is no allowance for commissions paid to insurance advisers for providing advice to PHB plan members or employers. - Similar to most private group plans, PHB beneficiaries would be required to contribute 20 percent of the claim cost, subject to an out-of-pocket cost of up to $1,500 annually ($375 per quarter).

Reviewers noted that $1,500 would be higher than beneficiaries would pay under Trillium ($1,500 / 0.04 = $37,500). The low-pay threshold is about $36,000 annually, assuming 40 hours per week and 52 weeks paid. This could be the earnings ceiling below which a sliding scale of subsidies could be implemented to ensure PHB out-of-pocket costs are never more than would be paid under the Trillium drug plan. - There will be exemptions and/or subsidies for the 20 percent of workers who earn less than the low-pay threshold ($17.33 per hour in 2021).

Low pay is more prevalent in non-standard employment, so more than 20 percent of eligible beneficiaries could receive a subsidy. That threshold should be adjusted annually to remain at two-thirds of Ontario’s median hourly wage. The cost of subsidies and exemptions cannot be estimated with the available information. - Taxation would be similar to and no less advantageous to employers and workers than current employer-sponsored or trusteed plans. This includes employer and worker deductibility of PHB contributions and that workers are not taxed on PHB benefits.

- Pre-existing health conditions will be covered, insurers must cover every worker and an annual open enrolment period should occur if a competitive model is used.

- A tendering or review process should identify at least three insurers that will agree to meet all carrier criteria, including regulation, reporting and other minimum standard requirements.

- The province would waive its premium tax (2 percent) and sales tax (8 percent) on premiums. Using the sum of projected costs for claims ($3.2 billion to $4.5 billion) and administration ($95 million to $135 million), less one-third for the government’s notional share of these costs, these forgone taxes can be estimated at between $220 million and $309 million.

- There would be no change to other federal or Ontario health or social services programs.

- The status quo of group and association insurance would continue. A PHB plan will be phased in over time and may eventually eliminate individual health insurance plans given their lower coverage and higher cost.

- Employers would be mandated to provide a standard PHB plan unless the employer sponsors a group plan of at least equal scope. This would eliminate most existing plan terminations and the threat of carving out PHB entitlements.

- All Ontarians would be mandated to have insurance at least equivalent to the PHB plan. (A voluntary plan would allow individuals to use their knowledge or expectation of their personal health to choose whether to enrol, ultimately attracting an unsustainable mix of high-cost members into the plan.)

- Health professionals; e.g., pharmacists, dentists, optometrists and counsellors should hold their fees at current reasonable and customary private coverage levels.

- Elasticity of demand can be estimated from other studies. For example, Law (2018) concluded elasticity of -0.1 to -0.3 for drug insurance would be reasonable in Canada, meaning demand is not affected much by price except perhaps for those with lower incomes. Elasticity may also vary by drug or by dental procedure.

- No assumption can be made about the ability of new PHB spending to avoid or delay future health and social system costs. As well, no assumptions can be made about the effects of changes in employment status or migration between public and private health and dental plans.

6. RegulationLow pay is more prevalent in non-standard employment, so more than 20 percent of eligible beneficiaries could receive a subsidy.

Legislation will be needed to enable a portable benefits plan in Ontario. Regulation is then required to operationalize the law and to manage the more practical aspects.

Within an SHI model, controls on private health insurers are required to ensure the public interest is met and held above the interests of shareholders. That requires a government to decide the degree of regulatory intervention in the insurance market. The amount of consumer protection should be proportionate to the importance and scope of the role insurers play (Sekhri and Savedoff 2006). Health insurance is only lightly regulated in Canada (Hurley and Guindon 2008).

According to Kutzin (2001), regulation may include:

- Prohibiting coverage limits or exclusions related to age or health status;

- A defined minimum level of coverage, including out-of-pocket expenses;

- Marketing and competition;

- Insurer risk-sharing to stabilize premiums;

- Consumer protection and decision-appeal mechanisms;

One reviewer noted that only advisers licensed by Ontario’s Financial Services Regulatory Authority are able to provide advice on individual health insurance plans in Ontario. If multiple plans and carriers enter the PHB market over time, then this advice may be needed. As an alternative, the Netherlands provides consumer advice and market oversight through a stand-alone regulator (ACM – see Case Review). and - An open enrolment period in which people can switch insurers without penalty.

Insurer regulation is necessary to address concerns about scope of coverage, administration costs, plan pricing, quality, waiting periods, limitations and exclusions, and claim payment accuracy. Policy would determine if private insurers can sell additional coverage and under what conditions. Like public utilities, PHB plan regulation would allow insurers to make reasonable returns for shareholders, which is also in the public interest.

It is crucial to strike the right regulatory balance so that insurers can afford to invest in product and service innovation. Insurer regulation need not be unduly stringent. Health insurers in Quebec are self-regulated and required by law to file an annual report with the government. However, the law provides insurers with significant latitude.

Such regulatory requirements become financially and administratively feasible when an entire population or a very large cohort is required to enrol. Concerns about adverse selection and knowledge asymmetry by patients or about countervailing risk selection (“cream-skimming”) by insurers can then be significantly mitigated.

Government policy also decides the place of competition among insurers, which can impact consumer choice and the availability of additional (top-up) coverage. For example, competition is a core principle of SHI in the Netherlands. Properly managed and regulated, competition can facilitate innovation in plan design, member services and cost management.

7. Policy Conflicts and Political Risk

As noted, Ontario’s PHB initiative needs to accommodate federal government commitments to provide a national dental plan. The plan’s first phase, a cheque to compensate parents for presumed dental costs for children under age 12, was launched in December 2022. A permanent plan is to be implemented in 2025. Eventually, there may also be some form of national pharmacare. It is unclear how a portable plan would be coordinated with existing public and private health and dental plans or workers’ compensation benefits, and how employers would respond if a new portable plan requires them to contribute.

The next Ontario election is scheduled for 2026, so there is plenty of time to properly consult, plan and potentially implement a PHB plan. Learning from OHIP+ and the US Affordable Care Act, the plan ought to be stable once it is launched and then effectively evaluated to ensure it meets public need and program goals. Strong management, governance and communication will encourage public support, which will in turn mitigate the risk of overtly political intervention that negatively affects beneficiaries, funders or providers.

8. Considering a Transition

Caution is necessary in planning a transition to a new PHB plan. Essential considerations include a compelling strategy, clear goals, sufficient consultation, adequate planning and implementation time, multilingual communication, implementation in stages and, likely, a pilot project. Examples of inadequate planning exist in three Canadian provinces.

In April 2014, New Brunswick proposed mandatory employer funding for a New Brunswick Drug Plan that would cover the 20 percent of residents who were uninsured.

Meanwhile, in its 2013/14 budget, Alberta estimated that between 20 percent and 27 percent of its population had no drug insurance. It then announced “comprehensive drug…benefit coverage for all Albertans.”

For its part, the Ontario Liberal government in 2017 announced OHIP+, a new drug plan for residents under age 25. The plan was very quickly implemented on January 1, 2018, largely eliminating the need for private coverage for this cohort. However, shortly after the 2018 provincial election, the new Progressive Conservative government largely reversed the former government’s plan and another transition period was required, all in just 15 months. The majority of patients were swept back to private plans if they still had access. Private plans and OHIP+ were not coordinated for claim payment, and some patients lost access to previously approved drugs due to the smaller public formulary or refusals under the province’s Exceptional Access Program.

Experience in these three provinces reinforces the need to properly plan, consult and implement a new PHB plan. In all these cases, implementation suffered from inadequate coordination with patients and their families, prescribers, dispensers, employers and health insurers.

9. Limitations

As stated, this current estimate of the scope, eligibility, cost and cost-sharing of a PHB plan suffers from inadequate data and the need for many assumptions. The conditions of coverage, such as mandated employer and worker participation and funding, are not yet clear.

Additional stakeholder consultation will help focus the interests and positions of the government and other parties. Priorities and process can then be established. Qualitative research collected through opinion leader interviews and focus groups will help identify and understand stakeholder perspectives and opinions. This contextual information is important and complementary to quantitative data.

10. Conclusions

This paper has described the purpose of portable health benefits and how such a plan might work in Ontario. There is an important unmet need for better access to supplementary health benefits for millions of Ontario workers who don’t qualify through their employers.

- The need for a PHB plan is driven by steadily evolving changes in the workplace that have increased the number of workers in non-standard employment who do not have access to employer-sponsored supplemental health benefits. While certain defined population cohorts are eligible for publicly funded health services beyond hospital and physician care, working age and employed residents are typically excluded from essential healthcare benefits such as prescription drugs, dental, vision and mental health.

- PHB plans should ensure rough equity with health benefits provided to most permanent full-time employees and provide tax benefits to employers and workers that are as favourable as those under existing group insurance plans. Extending existing provincial entitlement programs for drug, dental and vision care is likely unacceptable to workers because the benefit scope is much less and also to the government because it would bear the full cost of those improvements.

- A review of available and high-quality data indicates that between 3.5 million and five million Ontario workers may benefit from a PHB plan, although confidence in this range is not high. Non-standard employment workers typically work in part-time, temporary, contract or gig positions, or are self-employed.

- In recent years, federal policy has resurrected interest in some form of national drug insurance (pharmacare). The first phase of national dental insurance was launched in late 2022 with a near-universal plan to be completed in 2025. A PHB plan is in many ways a competitor to these broader national programs, although it may be financially and politically easier for one province to launch a PHB plan for targeted beneficiaries.

- PHB plan financing is assumed to be shared among employers, workers and the government. Total costs will depend on the number of beneficiaries, the plan design, administration, provider costs and how program costs will be shared. The government should consider the loss of premium and sales taxes if these are waived under a PHB plan and how to mitigate or eliminate the program threat of employers terminating their existing health benefit plans and transferring plan members and risk to a PHB plan.

- In the US, there are several examples of state- and city-legislated portable workers’ compensation, medical and retirement plans. In Canada, multiple-employer trusteed health and retirement plans have existed for decades and closely resemble how a PHB plan might operate.

- Social health insurance is a good foundational model for a PHB plan because it relies on the existing structure of private-sector players, administration and financing systems, and does not involve a significant increase in public funding.

- Using a mid-level plan design and the assumptions noted in this report, the first-year claim cost of a PHB plan could total $3.2 billion to $4.5 billion. Administration costs may be about 3 percent more. If beneficiary cost sharing is 20 percent, then claim costs would be commensurately reduced. The total worker contribution of premiums and coinsurance must be considered in aggregate. Exemptions for lower-income residents and an income-based cap on out-of-pocket costs need to be estimated.

- Insurers, pharmacy benefit managers and TPAs already have systems in place that can administer and manage a PHB plan. A competitive bidding process could be useful to identify one or more PHB plan administrators.

- Government needs to consider whether and how to regulate health insurance so that the industry meets social, patient and employer needs as well as the commercial needs of its owners (policyholders or shareholders). Regulation operates along a continuum from light (e.g., Quebec’s drug insurance) to heavier (European SHI systems, when performance and risk-sharing data are available).

- Employers have different needs, preferences and motivations than public health care plans, and those needs must be carefully considered since PHB plans will be partly paid by them.

- It is recommended that a PHB plan include an individual mandate for all workers and their families who are not otherwise eligible for employer-sponsored, association or individual health plans. This approach is equitable and will spread risks and keep per-capita costs affordable to each payer and sustainable over time.

- Similarly, all employers should be mandated to provide a benefit plan at least as generous as the PHB plan, with exemptions provided for very small or new businesses. The government can expect significant pushback from some segments of the small business sector. There are three offsetting arguments: First, about half of small employers already provide health benefits; The additional cost for those who may soon be mandated to do so is unlikely to be onerous and may boost employee satisfaction and loyalty; and Employers, given current skills shortages, are more likely now to accept a PHB plan or improve health coverage with additional benefits to help recruit and retain workers.

- If managed by TPAs or insurers, PHB plan administration should not be a major deterrent for small employers.

- A PHB plan presents a number of winners, losers and some unknown impacts. Governments should anticipate all these but pay closer attention to those who may lose from a PHB plan.

- The transition to add a PHB plan must include deep and regular consultations and be carefully managed to avoid disruption to individuals and the existing group and association health benefit market.

References

(ACM) Netherlands Authority for Consumers & Markets. 2017. “Consumers could save substantially on their health insurances [sic]. About 33% switched insurers at least once in the previous ten years.” News release, December 1. Available at: https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/consumers-could-save-substantially-their-health-insurances

BMO Wealth Management. 2018. The Gig Economy: Achieving Financial Wellness with Confidence. Available at: https://commercial.bmo.com/media/uploads/2019/01/08/bmo_gig_economy_infographic_en.pdf

Banks, C., S. Steward. 2021. The Original Portable Benefit. The Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. August. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Original-Portable-Benefit.pdf

Barnes, S., L. Anderson. 2015. Low Earnings, Unfilled Prescriptions. Wellesley Institute. Available at https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/publications/low-earnings-unfilled-prescriptions/

Benefits Canada Healthcare Survey. 2022. p.26. Available at: https://www.benefitscanada.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2022/09/BCHS-Report-2022-ENG-final.pdf

Bonnett, C. 2020. “Fixing an Accident of History: Assessing a social insurance model to achieve adequate universal drug insurance.” PhD dissertation. Available at: https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/15724/Bonnett_Christopher.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Busby, C. 2020. “A drug, dental and mental health plan for uninsured Canadians.” Policy Options. Institute for Research on Public Policy. Available at: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/october-2020/a-drug-dental-and-mental-health-plan-for-uninsured-canadians/

CADTH. 2022. “Building toward a potential pan-Canadian formulary: A report from the advisory panel.” Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/Pan_canadian_Formulary/Pan-Can-Formulary-Report-Final.pdf

Canada Revenue Agency. Income Tax Folio S2-F1-C1, Health and Welfare Trusts. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/technical-information/income-tax/income-tax-folios-index/series-2-employers-employees/series-2-employers-employees-folio-1-specific-plans-offered-employers-employees/income-tax-folio-s2-f1-c1-health-welfare-trusts.html#toc1

Canadian Institute for Health Information 2022. National Health Expenditure Trends 2022. Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-health-expenditure-trends

Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. 2022. Canadian Life and Health Insurance Facts-2022. November. Available at: http://clhia.uberflip.com/i/1478447-canadian-life-and-health-insurance-facts-2022-edition/15

Dobson K.G., S.N. Vigod, C. Mustard, P.M. Smith. 2021. “Major depressive episodes and employment earnings trajectories over the following decade among working-aged Canadian men and women.” Journal of Affective Disorders 285: 37-46.

Gagnon-Arpin, I., W. Chen, C. Leaver. 2022. Understanding the Gap 2.0: A Pan-Canadian Analysis of Prescription Drug Insurance Coverage. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada.

Gervis A., S. Steward, C. Banks, M. Siddique. 2021. Portable Benefits in Action. A Roadmap for a renewed work-related safety net. The Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. December. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/portable-benefits-in-action-a-roadmap-for-a-renewed-work-related-safety-net/

Ginneken, E. van, W. Shäfer, M. Kroneman. 2010. “Managed competition in the Netherlands: an example for others?” Eurohealth 16(4): 23-26.

Grootendorst, P., E.C. Newman, M.A.H. Levine. 2003. “Validity of self-reported prescription drug insurance coverage.” Health Reports 14(2): 35-46. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-003-x/2002002/article/6437-eng.pdf?st=uvTclki8

Health Canada. 2010. “Summary report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2007-2009.”

Hurley, J., G.E. Guindon. 2008. “Private Health Insurance in Canada.” Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis. CHEPA Working Paper 08-04.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. 2021. “Key Small Business Statistics 2021.” Tables 1 and 5. Available at: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/sme-research-statistics/en/key-small-business-statistics

International Labour Organization. 2016. “A challenging future for the employment relationship: Time for affirmation or alternatives?” Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/WCMS_534115/lang--en/index.htm

Jeon, S-H., H. Liu, Y. Ostrovsky. 2019. Available at: “Measuring the gig economy in Canada using administrative data.” Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2019025-eng.htm

Johal, S., W. Cukier. 2019. “Portable Benefits: Protecting People in the New World of Work.” Public Policy Forum. January. Available at: https://ppforum.ca/publications/portable-benefits/

Johal, S., J. Thirgood. 2016. Working Without a Net. Mowat Centre, University of Toronto. Available at: https://mowatcentre.munkschool.utoronto.ca/announcement-from-the-mowat-centre/

Kutzin, J. 2001. “A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements.” Health Policy 56: 171-204.

Lankin, F., M.A. Shiekh. 2012. Brighter Prospects: Transforming Social Assistance in Ontario. A Report to the [Ontario] Minister of Community and Social Services. This report is no longer available on the Government of Ontario website. Available at: https://www.crwdp.ca/sites/default/files/Research%20and%20Publications/Enviornmental%20Scan/16.%20Commission%20for%20the%20Review%20of%20Social%20Assistance%20in%20Ontario/Brighter%20Prospects%20-%20Transforming%20Social%20Assistance%20in%20Ontario.pdf

Law, M.R. 2018. Cost-related Barriers to Prescription Drug Access in Canada. A report prepared for the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare.

Law, M.R., L. Cheng, A. Kolhatkar et al. 2018. “The consequences of patient charges for prescription drugs in Canada: a cross-sectional survey.” CMAJ Open 6(1): E63-E70. DOI:10.9778/cmajo.20180008

Levy, D., J. Purvis, H. Averns. 2019.” Changes to OHIP+ mean some kids will go without life-saving medicine.” Healthy Debate, April 17.

Lewchuk, W., M. Lafleche, D. Dyson et al. 2013. It’s More than Poverty: Employment Precarity and Household Well-being. Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario (PEPSO), McMaster University Social Sciences, United Way Toronto. Available at: https://pepso.ca/documents/2013_itsmorethanpoverty_report.pdf

Lischko, A.M., S.S. Bachman, A. Vangeli. 2009. The Massachusetts Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector: Structure and Functions. The Commonwealth Fund, Issue Brief. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2009/may/massachusetts-commonwealth-health-insurance-connector-structure

Manulife. 2013. Small Business Research Report.

Mercer. 2022. Resources for tracking state and city retirement initiatives. https://www.mercer.com/our-thinking/law-and-policy-group/resources-for-tracking-state-and-city-retirement-initiatives.html

Mitchell, C.M., J.C. Murray. 2017. The Changing Workplaces Review: An Agenda for Workplace Rights. Ontario Ministry of Labour. May. Available at: https://files.ontario.ca/books/mol_changing_workplace_report_eng_2_0.pdf

Nichani, P., G.E. Trope, Y.M. Buys, S.N. Markowitz, S. El-Defrawy et al. 2021. “Frequency and source of prescription eyewear insurance coverage in Ontario: a repeated population-based cross-sectional study using survey data.” CMAJ Open 9(1): E224-32. Available at: https://www.cmajopen.ca/content/cmajo/9/1/E224.full.pdf

Ontario Workforce Recovery Advisory Committee (OWRAC). 2021. The Future of Work in Ontario. Available at: https://www.ontario.ca/files/2022-06/mltsd-owrac-future-of-work-in-ontario-november-2021-en-2021-12-09.pdf

Parliamentary Budget Officer. 2020. Cost estimate of a federal dental care program for uninsured Canadians. Fig. 1.2. https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/web/default/files/Documents/Reports/RP-2021-028-M/RP-2021-028-M_en.pdf

Reder, L, S. Steward, N. Foster. 2019. Designing Portable Benefits: A Resource Guide for Policymakers. The Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. June. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Designing-Portable-Benefits_June-2019_Aspen-Institute-Future-of-Work-Initiative.pdf

Rolf, D., S. Clark, C. Watterson Bryant. 2016. Portable Benefits in the 21st Century. The Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. June. Available at: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/upload/Portable_Benefits_final2.pdf

Sekhri, N., W. Savedoff. 2006. “Regulating private health insurance to serve the public interest: policy issues for developing countries.” International Journal of Health Planning and Management 21: 357-92.

Statistics Canada. 2022a. Trade union density rate, 1997 to 2021. Quality of Employment in Canada. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-28-0001/2020001/article/00016-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. 2022b. Pharmaceutical access and use during the pandemic. November. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2022001/article/00011-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. 2022c. Quality of Employment 2021. May 30. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/220530/dq220530d-eng.pdf?st=HK5oqKh1. Part of: Employees with low pay, 1998 to 2021. Catalogue 14280001, Quality of Employment in Canada.

Statistics Canada. 2020. Canadians report lower self-perceived mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. April 24. Available at: https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/statcan/45-28/CS45-28-1-2020-3-eng.pdf

Statistics Canada. 2019a. Dental Care, 2018. Catalogue 82-625-X.