To: Ontario Municipalities

From: Benjamin Dachis

Date: August 23, 2023

Re: What Municipal Financial Audits are Likely to Find

In late July, the Ontario government announced details on a financial audit of select municipalities to assess the impact of provincial changes to development-related fees.

The audit will likely find that the change had some financial impact on the ability of cities to fund some municipal infrastructure and should help all parties land on a fiscal cost. What comes next is harder: It requires deeper reform of development fees to reduce the per-unit charges on housing.

The first problem the audit will likely find is that Ontario cities are collecting, but not immediately deploying into infrastructure, large amounts of development charges. Cities levy development charges to finance infrastructure. These charges get passed on to homebuyers through higher prices.

A previous C.D. Howe Institute study found that between 2009 and 2018 Ontario municipalities collected $17.4 billion in development charges, $6.4 billion dedicated for water infrastructure as the largest single item. In that 10-year period, cities spent about 90 percent of development charges collected.

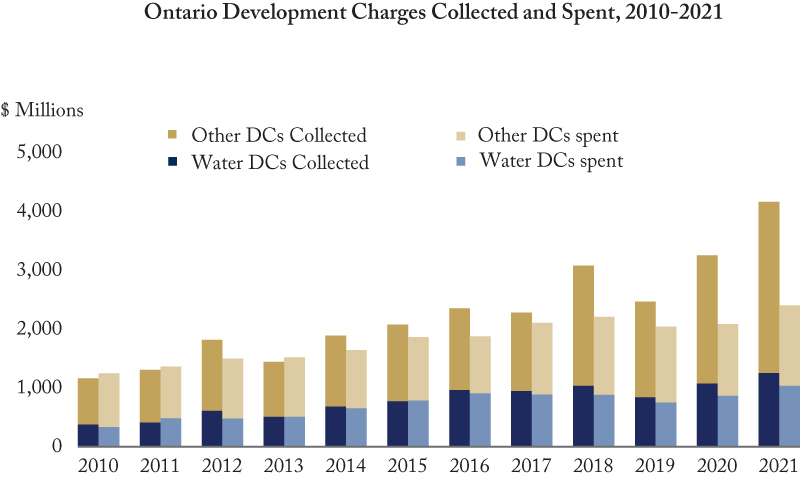

The situation is now significantly worse (see Figure). Total development charges collected in 2021 (the last year in which city-by-city data is available from province) they reached more than $4 billion. In 2021, only a little more than half of the amount of development charges collected went either to pay off capital-related debt or directly into hard infrastructure that year.

The problem is indeed worse than these figures indicate. The Figure shows cash flows in and out of reserves. The audit will likely focus on immediate cash costs to cities. Modern accounting principles focus not on cash, but on the life of the asset money buys. That’s called accrual accounting. When cash from development charges is turned into assets, they operate for many years. When cities re-express expenses on water and wastewater on an accrual basis, as they do in financial statements, the annual services residents get are a fraction of the actual upfront expense. Cash budgets obscure this timing mismatch.

Although many Canadian cities levy development charges (notably, Quebec cities largely have none), Ontario cities levy much higher development charges than other similar cities. Partly as a result, large Ontario municipalities’ (single- and combined lower- and upper-tier) deferred revenues they report in financial statements, of which development charges are a major component, are much higher than in other major cities in Canada.

Ontario’s development charges are both higher than in other provinces and the money isn’t going back to services for residents in a timely manner. It is time to reform the development charge system.

What are the potential solutions? A utility model can re-orient financing for water and wastewater away from upfront municipal financing on the backs of homeowners. A lower upfront charge on homebuyers will reduce housing costs. Instead, customers will pay the same charge over time, passed on in long-run user fees.

Cities face lower interest rates than homebuyers. Toronto is issuing bonds with coupons at 4.5 percent, while mortgages now at long-term fixed rates are in the 6- to 7-percent range. Cities will pay less total interest to finance debt than if debt were passed onto homebuyers. Cities are issuing longer-term debt than household mortgages. This means that despite the term risks, lenders see municipal bonds as lower-risk bets than households. Utilizing this lower risk can mean long-term cost savings.

User fees are more difficult for other city services – think parks – and it is tough to localize property taxes to capture the local benefit of such spending. But a land-value tax on new development is one solution, which reflects varying property values in a municipality.

And indeed, Ontario announced such a tax (called a Community Benefit Charge) in 2019, which is capped at 4 percent and applies to buildings with more than five stories and 10 units. Cities began collecting this charge in September 2022. Ontario should increase the percentage cap while lowering what cities may charge in per unit development charges.

A higher Community Benefit Charge is a way that cities can collect that upfront revenue while supporting housing development. A charge based on land value encourages developers to build smaller, cheaper, and less profitable units than if they were facing a per unit development charge. A land value charge by design automatically collects more in high value areas – e.g. close to transit – while taking a lower share of construction costs in areas with less development interest and lower land value. If cities calculated the amount of Community Benefits Charge due based on average area land value, developers would seek to build more homes than if they paid the same dollar amount in per-unit development charges. It’s a win-win.

Developers, who pass costs onto homebuyers, are paying upfront charges expecting to get water infrastructure or other services. The province-wide data shows they are not receiving them in a timely manner or in a way that corresponds to when residents get services back. As municipal audits begin, it’s time to think about what the ideal policy approach is, then use the audits to calibrate exactly how to set future utility systems and Community Benefit Charges to fill these gaps.

Benjamin Dachis is Associate Vice President of Public Affairs at the C.D. Howe Institute.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.