From: Brian Lewis

To: Ontario taxpayers, infrastructure policy makers and investors

Date: February 26, 2024

Re: Practical Advice for the Ontario Infrastructure Bank

The provincial government recently announced the creation of an Ontario Infrastructure Bank to help build more infrastructure faster while lowering taxpayer costs.

The new bank would do this by leveraging private sector capital and expertise through project agreements that allow for more flexible sharing of risks and returns than conventional project contracts. A broad range of priority areas were identified, including long-term care homes, energy infrastructure, affordable housing, municipal and community infrastructure and transportation.

The bank cannot reasonably be expected to simultaneously achieve the three competing objectives of more, faster, and lower cost. Achieving even one of these three objectives without compromising the other two would be an accomplishment. Prevailing capacity constraints makes the goal of delivering more infrastructure particularly unrealistic and creates the possibility that by adding more funding and projects, the new bank will increase competition for scarce sector resources, ultimately slowing infrastructure completion and driving up taxpayer costs.

The province is committed to this plan despite lacking a compelling case for it. As such, it should do so in a way that maximizes the benefits and diminishes potential risks. Specifically, the province should focus the bank on the timely delivery of long-term care homes and affordable housing guided by robust accountability guidelines that clearly protect the interests of provincial taxpayers.

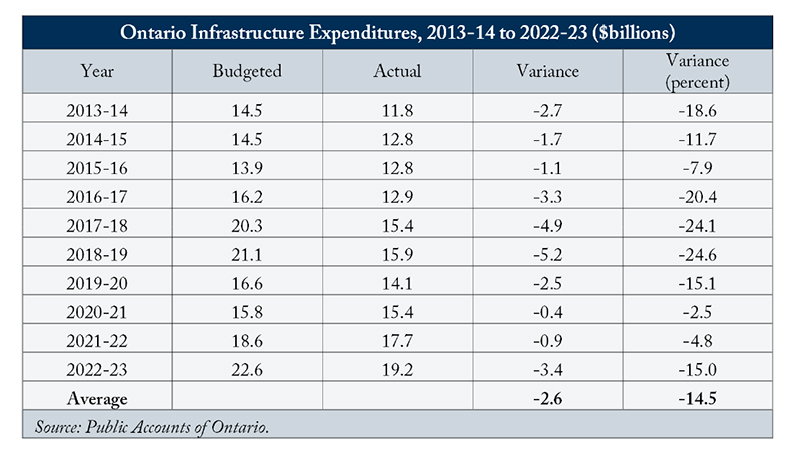

Attracting more capital will not get more infrastructure built. A shortage of money has not been a problem. The province has never come close to spending the funds it annually allocates to infrastructure. In each of the past 10 years Ontario has significantly underspent its infrastructure budget, by an average of $2.6 billion, or 14.5 percent below the budget target.

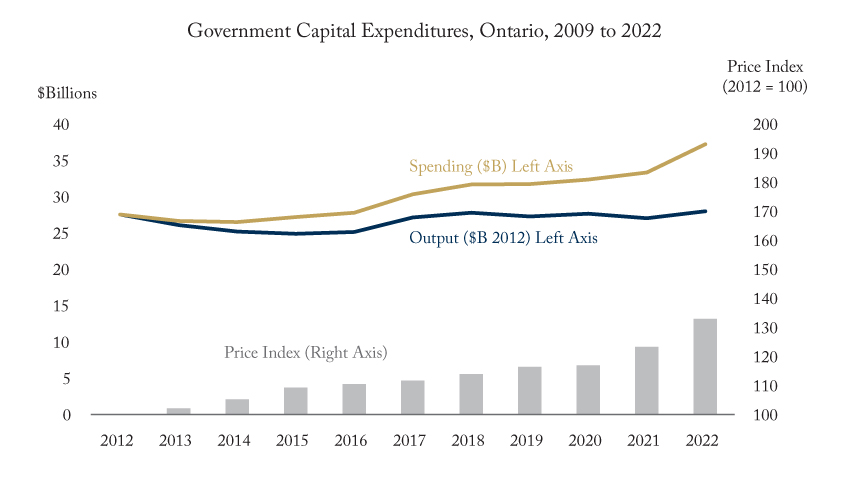

Another way to look at this is provided by provincial economic data that shows capital expenditures by all levels of government in the province combined in the province have increased significantly (35.2 percent in 2022 compared to 2012) over time, and these higher expenditures have been absorbed mainly by prices, which rose 33 percent while output in real terms, up 1.6 percent, barely nudged ahead.

Persistent provincial underspending and the inability to generate growth in real output over time makes it doubtful that more funding will build more infrastructure.

The province generally attributes annual shortfalls in infrastructure expenditures to “revised construction schedules," indicating the challenges are related to project delivery rather than financing. Similarly, an Ontario Construction Secretariat survey showed the most significant challenges across the sector are the availability and cost of labour and materials. New financing mechanisms made available through an infrastructure bank are not going to solve the problem.

The theory of infrastructure banks is that including private sector partners and funding should result in government infrastructure delivered more efficiently and effectively. Unfortunately, quite the opposite has too often been the case, as private-public partnerships have produced some of the worst performing infrastructure projects in the country, as outlined in a recent paper from Ontario 360 at the Munk school. For example, large-scale projects such as the Ottawa Confederation and Toronto Eglinton Crosstown light rail lines have been plagued by technical challenges, construction delays and cost overruns. Even when projects involving the private sector are delivered on time and within budget, they tend to come with a higher cost to the taxpayer. Projects under the alternative financing and procurement approach resulted in significantly higher costs ($8 billion) to the province, Ontario’s Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk reported in her 2014 Annual Value of Money Report.

One of the primary benefits of an infrastructure bank is the potential to offer a broader range of financing arrangements with risks – both upside and downside – being shared between the public and private sectors. This is true in theory. In practice? Private-public partnerships for infrastructure have “come to be seen less as a genuine partnership and more as a complex form of contracting that privatizes profits and socializes risk,” the Ontario 360 paper concluded.

The province will undoubtedly proceed with its infrastructure bank despite the lack of a compelling need and its related risks. As such, the Ontario’s new bank should focus on one or two priority areas with solid public needs and a clear private sector role. Long-term care homes and affordable housing are relatively high need, low-risk options. Private sector partnerships should be guided by a robust investment framework that would stand up to the scrutiny of the Auditor General and an increasingly skeptical public. The Auditor General should be engaged to opine on the investment framework and potentially on specific investments to ensure taxpayer value for money. Finally, the bank should be patient in its deal-making because accountability and results are far more important than speed.

Brian Lewis is a senior fellow at the C.D. Howe Institute and the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and former Chief Economist for Ontario.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.