From: Ross Finnie, Richard E. Mueller, and Arthur Sweetman

To: Provincial Ministers of Education and Immigration; Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Date: July 24 2017

Re: Education is Key to Immigrant Integration in Canada

For 2017, Canada increased its permanent immigration target to almost 1 per cent of the population. And, happily, the relatively high level of foreign born in Canada’s population coincides with popular support for more. Numerous policies support this coincidence and the rapid social change it entails.

Official anti-discrimination and multiculturalism policies matter. So does selection of who can come. Last year, about 54 per cent of immigrants to Canada were economic migrants. A further 27 per cent were family members of Canadians, a large share of whom are previous immigrants, and 19 per cent were refugees.

Canada’s modern history as a successful immigrant-receiving nation also, however, owes a lot to its education system. The higher levels of educational attainment among both childhood (first-generation) immigrants who arrived with their immigrant parents and second-generation immigrants born to parents who came to this country than those born to Canadian-born parents speaks to their determination and perseverance, and also to the openness and flexibility of the system they join. (This memo, based in part on a Times Higher Education article focuses on childhood immigrants and the children of immigrants who have the opportunity to, at least in part, go through the Canadian education system rather than those who finished their schooling in other countries.)

Even early childhood immigrants who arrive with language skills that lag those of native-born Canadians, and those arriving from countries with education systems that don’t perform as well as Canada’s find educational success here. Indeed, this also applies to children who arrive as refugees. They, too, are more likely to graduate from university than children born to non-immigrant Canadian parents.

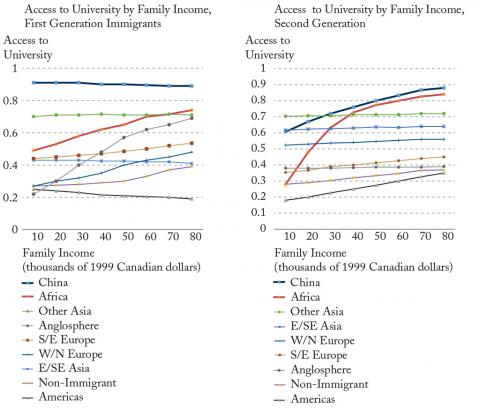

Both childhood first- and second-generation immigrants from almost all regions have higher university attendance rates compared to the Canadian-born, although those from China, Africa, and certain parts of Asia lead the way. This result holds even when taking into account factors such as parental education, secondary school grades, PISA scores at age 15 and family income: all considered important predictors of university attendance. The accompanying figures show the relationship between university access and family income as an example.

These patterns suggest that our education system supports the children of immigrants’ success in Canada. This good news story needs to be told more often, even as we must continue to keep an eye out for further improvements in how Canada can attract and integrate more skilled immigrants.

Ross Finnie is professor and director of the Education Policy Research Initiative (EPRI) at the University of Ottawa, Richard E. Mueller is professor at the University of Lethbridge and associate director of EPRI, and Arthur Sweetman is professor at McMaster University and associate director of EPRI.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.