Canada’s small and medium enterprises are facing numerous challenges that impede their ability to scale up. The C.D. Howe Institute has launched a policy working group to explore ways governments can help Canada’s SMEs grow by removing barriers to the availability and access to patient long-term financing, and deepen capital markets. This Memo is the first in a series outlining the context and offering policy recommendations.

To: Canada’s Policymakers

From: Jeremy M. Kronick and Mawakina Bafale

Date: July 26, 2022

Re: Deepening Canadian Capital Markets

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) employ a disproportionately large number of Canadians – about 85 percent of the total private sector labour force last year. As a result, economic growth in this country, and the required productivity improvements, will be driven by how these businesses grow over time.

Canada’s track record suggests we are pretty good at getting SMEs started but less so growing them or getting them to stay in Canada. While there are many reasons for this, access to financing, and in particular the lack of depth of capital markets in this country, is one of them.

So, what can be done? Where to start?

Let’s begin with the numbers heading into the pandemic – in part because data in this area can be slow developing, but also because a black swan event such as COVID-19 can skew interpretations.

In 2018, the share of total outstanding loans to SMEs relative to large business loans hit its lowest level since 2000. This despite the fact that over the period from 2007 to 2018, 90-day delinquency rates on loans to small businesses fell from 0.70 percent to 0.54 percent (it is much more stable for medium-sized businesses.)

The next year – the last before the pandemic – was even worse, with the share of total outstanding loans to SMEs falling further, despite the delinquency rate improving to 0.45 percent. Beyond outstanding loans, new loans to SMEs also fell in 2019, and the share of new loans that go to SMEs has been falling since 2011.

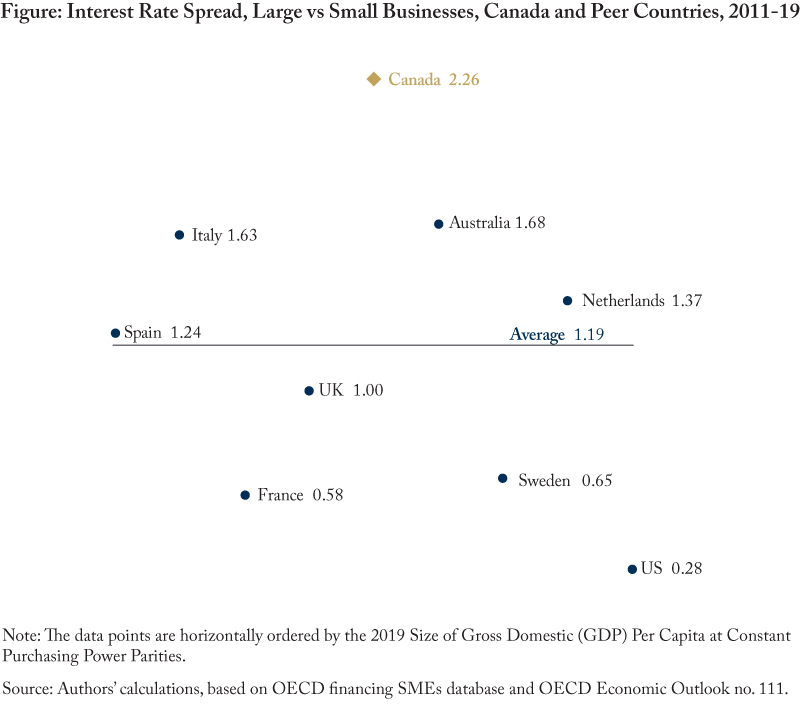

One explanation is the interest rate SMEs face on their loans relative to loans to large enterprises – we’ll call it the interest rate spread – is the highest in Canada compared to a number of our traditional OECD comparator countries (the US, France, Sweden, UK, Italy, Australia, and the Netherlands.) From 2011 to 2019, Canada’s interest rate spread averaged 2.26 percent, with the next highest, Australia, at 1.68 percent, a gap of nearly 60 basis points (see Figure). The US, by comparison, had an average spread of only 0.28 percent.

The gap cannot be explained away by looking at SME interest rate levels. Over the 2011-2019 period, SMEs in Canada paid an average of 5.33 percent on their loans, coming in only ahead of Australia at 5.97 percent. And, in 2019, the first year Canada was not alone in last place for the spread – Italy and Australia shared that rank with us – Canada’s actual SME interest rate, at 5.3 percent, was the highest.

Many things drive interest rates, and Canada’s concentrated financial sector means there is scope to deepen capital markets to alleviate the interest rate sensitivity SMEs face from a dearth of alternatives.

One option is to look at ways to encourage more patient equity capital, lowering the reliance on debt financing. We could look south of the border to one of the 2010 measures in the US Small Business Jobs Act, which exempted from taxation capital gains realized on the sale of certain small business shares. Under this policy, investors qualify for the capital gains tax exemption if they hold qualified shares for at least five consecutive years, encouraging the kind of patience needed to grow SMEs.

Another option is to look at the incentive structure for mortgage lending versus lending to businesses. In Canada, the CMHC provides lenders of insured mortgages a 100-percent insurance guarantee, which makes mortgage lending essentially risk-free – clearly a more attractive option than lending to risky SMEs. On the one hand, applying a zero risk weight should open financial institutions up to more lending to businesses. However, on the other, profitable mortgage lending may crowd out business lending.

Since mortgage insurance is an effective tool to insulate the financial system from a housing crash, meaning there are strong positive externalities, we need to start by looking for ways to change the incentive structure at the margins. At present, mortgage insurance premiums are the same for every borrower at a particular loan-to-value ratio, regardless of borrower characteristics, e.g. credit scores. So, if two people put down a 10 percent down payment, they will be charged the same insurance premium regardless of their economic circumstances.

The idea behind risk-based pricing is we want to create the conditions for a more stable and efficient allocation of capital. By charging mortgage borrowers different premiums that take into consideration their risk profiles, capital will get more appropriately allocated, perhaps shifting some from housing towards businesses.

SMEs play a critical role in Canada’s economic engine. Their growth rates have been hampered by access to financing. Policymakers should look for ways to encourage more patient capital and alleviate barriers that discourage lending to businesses. The options presented here are a good first step.

Jeremy M. Kronick is associate director, research, at the C.D. Howe Institute where Mawakina Bafale is a research assistant.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.