From: Jeremy M. Kronick and William B.P. Robson

To: Business Leaders Concerned About Investment

Date: March 30, 2022

Re: House-Rich, Everything-Else-Poor

In the fall of 2020, barely noticed amid the stresses of COVID-19, Canada’s economy passed a peculiar milestone.

Residential investment surpassed all other business investment – more than for non-residential structures, machinery and equipment, and intellectual property products combined. That was unprecedented. As recently as the early 2000s, it would have been inconceivable. As a nation, we risk ending up with nice roofs over our heads, but without the incomes we need for everything else we want. House-rich, and everything-else-poor.

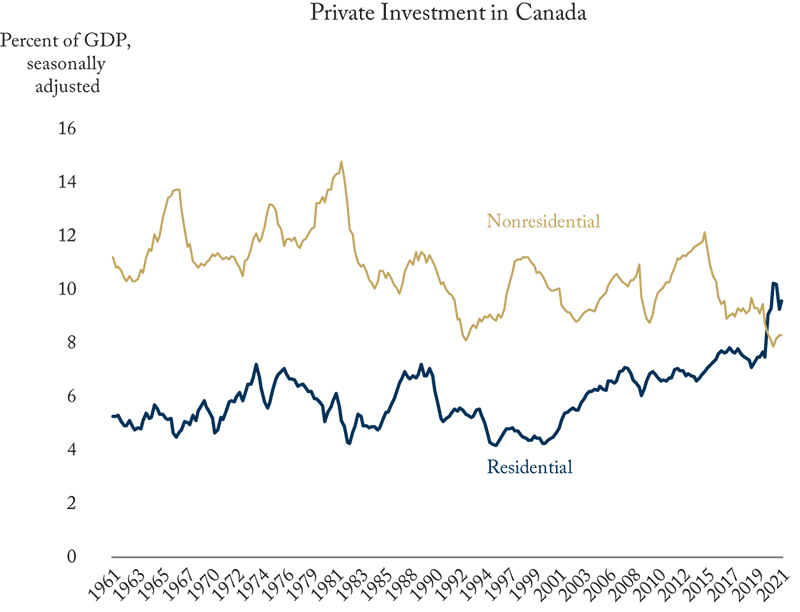

Because a growing economy and inflation make recent experience hard to compare with what happened decades ago, it helps to measure investment relative to GDP, as in the figure. Until the recession of the early 1990s, non-residential investment was typically above 10 percent of GDP. After that it averaged around 10 percent of GDP – until the mid-2010s, when it collapsed. Residential investment fluctuated around 5 percent of GDP until the 2000s, and it has been mostly up since then. The decline of non-residential investment after 2014 and the surge in residential investment after 2019 have put us in a completely new place – spending more on new houses, renovations and real-estate transactions than on everything businesses equip their workers with so they can hold their own against competitors abroad and, not incidentally, earn higher wages and benefits.

We can take some comfort from declining prices for many investment goods. Modern computers, for example, give businesses far more bang for the buck than those of the 1990s did. But that is true everywhere, and business investment in other countries, notably the United States, is far more robust than in Canada. Meanwhile, Canada’s residential investment is outstripping almost everyone else’s.

Comparing household mortgages to business credit reinforces the impression that something unusual has been going on in recent years. Because businesses finance most of their capital spending with internal funds, the total dollar amounts involved in all household mortgages outstanding have always exceeded those involved in business loans. But in the early 1990s, household mortgages were only about 50 percent more than business loans. By the early 2000s they were twice as big. A decade ago they were 3.5 times as big. They’ve since declined a bit in relative terms but are still 2.5 times the total of outstanding business loans. It seems borrowers like borrowing, and lenders like lending, against houses more than against plant, equipment and software.

We have nothing against housing. We like the roofs over our own heads. Moreover, robust construction, renovation and transactions gave spending and jobs a welcome boost during the pandemic. But other investment also matters. Without buildings, machinery, IP products and other tools, we cannot earn the incomes to buy what we need, including the public services we fund with our taxes, not to mention maintain those roofs.

One reason for surging inflation is that the economy’s productive capacity has not been able to keep up with supercharged demand fueled by low interest rates, transfer payments governments have financed with borrowed money, and people’s enthusiasm for spending in ways they could not during the pandemic.

The list of changes that could encourage more non-residential investment in Canada is long, but lenders’ preference for mortgages over business credit can help us prioritize. The spread between the interest rate charged to small and medium-size enterprises and the interest rate charged to large businesses is higher in Canada than almost anywhere else in the OECD, and markedly higher than in the United States. This stunts access to credit by the smaller businesses that employ the vast majority of Canadians.

One possible reason for this unusually big spread are policies that divert credit toward housing – in particular, the 100-percent, taxpayer-backed guarantee on insured mortgages at the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and the 90-percent guarantee on mortgages backed by private insurers. Government backstopping of mortgages can help mitigate or prevent financial crises, but Canada’s approach makes mortgage lending less risky than business lending across the board. Charging premiums for mortgage insurance that better reflect risk would reduce this bias.

Housing is good, but by going all-in Canadians may be getting too much of a good thing. To boost our productivity and generate the incomes we need for fast growth without inflation we also need non-residential investment.

We want solid roofs over our heads and good jobs, high living standards, and the public services that will ensure those houses are worth living in.

William B.P. Robson is CEO of the C.D. Howe Institute, where Jeremy M. Kronick is Associate Director, Research.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

A version of this Memo first appeared in the Financial Post.