From: Parisa Mahboubi and Mikal Skuterud

To: Sean Fraser, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

Date: February 6, 2023

Re: The Unintended Consequences of Category-Based Immigrant Selection

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) recently held consultations on plans aimed at giving the department more flexibility in how it prioritizes economic-class applicants for permanent residency.

The new rules will, in effect, free the immigration minister to bypass the existing system for selecting candidates, known as the Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS), to target applicants with particular “attributes” such as work experience in a particular occupation.

This may alleviate some labour shortages, but we see significant unintended consequences.

Leveraging immigration to boost average living standards in the population requires selecting immigrants whose Canadian earnings exceed average earnings in the pre-existing population, thereby pulling up average incomes and per capita GDP.

The CRS aims to achieve this by ranking and cream-skimming economic class candidates who have the highest expected Canadian earnings. This is estimated using data on the earnings of previous cohorts of immigrants who arrived with similar human capital characteristics. Of particular importance in the CRS calculation are education, age, language abilities, and Canadian work experience.

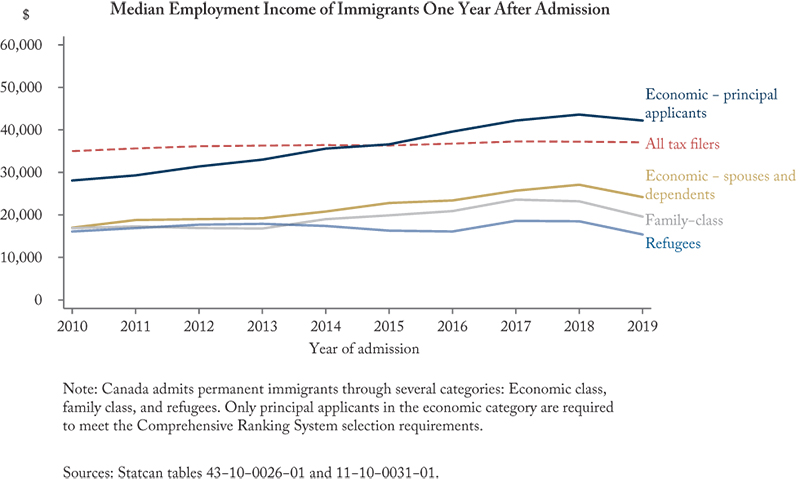

Recent analysis using Statistics Canada survey and census data, as well as our own examination of immigrants’ income tax records (see Figure below,) provides encouraging evidence that the CRS has contributed to rising earnings for newcomers since its launch in January 2015.

By prioritizing applicants’ occupations, IRCC hopes it can be more responsive to employer needs, as well as address Canada’s chronic labour shortages.

But accurately identifying labour market requirements and being sufficiently responsive is difficult, if not impossible. Tight labour markets can quickly become slack. By the time targeted immigrants arrive, their skills may no longer align with employer needs, thereby exacerbating long-standing mismatch issues between immigrant skills and job openings. For this reason, the CRS does not use specific occupational information in its calculation.

The raison d’être of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, which allows Canadian businesses to employ guest workers on limited-term contracts, is to meet temporary labour-market shortages. The objective of our permanent immigration system, on the other hand, should be to drive new employment growth in high-productivity sectors that are intensive in their use of skills and new technologies.

Unfortunately, we increasingly have a system where our temporary and permanent immigration systems are focused on the same objective – satisfying employers’ current labour needs. The risk is that the overall immigration system fails to do anything well.

An important advantage of the CRS is its transparency. Candidates can determine their own scores using a simple online tool and IRCC reports cutoff scores in their bi-weekly draws allowing unsuccessful candidates to identify what’s needed to be selected. The category-based selection system that IRCC is proposing compromises this transparency by leaving screening criteria to the whims of the minister of the day. This risks increasing applicant confusion and frustration and increases the need for immigration consultants and lawyers to help applicants navigate the system. At worst, it drives applicants with the best outside options to other countries.

Allowing the ministers to determine which candidate attributes are prioritized also risks politicizing the process. Research shows that while temporary worker inflows in Canada are responsive to the intensity of corporate lobbying, the same has not been true for permanent immigration. One explanation is that ‘point systems’ like the CRS remove immigrant selection decision making from the political realm in the same way that the Bank of Canada’s inflation mandate keeps its interest rate decisions from being politicized. Look for that to change.

In our view, prioritizing candidates’ occupational work experience in immigrant selection makes most sense in sectors where the competitive market mechanism to address labour shortages does not exist, such where wages are set by collective agreements or government regulation.

In these settings, labour shortages are less likely to induce the wage adjustments necessary to encourage job switching and training and education investments within the existing population. Chronic shortages of nurses and other healthcare workers are an important example.

Nonetheless, we question if it makes sense to prioritize applicants for permanent residency whose foreign work experience is in an occupation where credential recognition in Canada is problematic. It doesn’t really matter if credential recognition problems reflect genuine skill and competence issues, or the self-interested behaviour of professional associations. Either way, we are prioritizing applicants who will contribute relatively little to Canadian economic growth, thereby compromising the key objective of our economic immigration system.

In our view, IRCC’s planned reform of how it selects economic-class immigrants is just one step in a series of pandemic-era policies compromising the prioritization of skilled immigrants. The CRS has come to be seen by IRCC as a constraint rather than an effective quality-control mechanism. In prioritizing employers’ short-term labour needs, IRCC is being forced to lower the average CRS score of selected immigrants and, in turn, average expected earnings. The hard reality is that Canada’s newcomers continue to experience labour market challenges that are longstanding and exceptional. The risk is that the last decade’s significant gains will be undone.

Parisa Mahboubi is a senior policy analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute and Mikal Skuterud is professor of economics at the University of Waterloo.

To send a comment or leave feedback, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the authors. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.