The Study In Brief

- Credit unions represent an important part of the Canadian banking sector and, therefore, the Canadian economy. Outside of Quebec, at the end of 2021 credit unions held almost $280 billion in assets, representing about 7 percent of banking sector assets.

- While improving corporate governance has been part of the reform agenda for federal policymakers and banks since the financial crisis, less is known about how credit unions have evolved their governance practices and standards to address the growing complexity of banking.

- This E-Brief begins with a snapshot of the evolution and performance of the credit union sector over the 2012-2019 period, reviews the practices and board composition at some of the country’s biggest credit unions and makes recommendations for improvement.

- Among them: Clarity of purpose is critical as credit union boards determine what is behind the gap between their performance and that of the banks in terms of two key measures, namely return on assets and the efficiency ratio.

- Credit unions need to ensure that board and member dynamics are conducive to good communications, thereby increasing transparency and information flow to members and encouraging meaningful member engagement.

- Boards can guard against “capture” by providing management with a set of performance indicators and attendant incentives that create an efficiently run credit union to deliver meaningful benefits for members.

Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic and the inflationary pressures that followed have superseded the 2007-2009 financial crisis as the defining event of the new millennium, the latter is still shaping financial sector policymaking.

Even as the earlier crisis recedes from memory, financial sector policymakers continue to roll out a policy agenda built around what is believed to be a key cause of the financial crisis, namely poor corporate governance at large internationally active banks. The focus on corporate governance is built on the premise that, without effective oversight by the board of directors, managers may take actions that harm the interests of shareholders or other stakeholders – e.g., by taking excessive risks, failing to control costs or making poor investments. To carry out this oversight role, the board needs to have the appropriate skills, expertise and experience.

With this framing in mind, policymakers have paid increased attention to how corporate governance shapes the behaviour of financial institutions. In 2010, for example, as the financial crisis was abating, Canada’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) created a new governance division to review banks’ governance practices and their compliance with its governance guideline, first introduced in 2003, after a series of high-profile accounting scandals linked to governance failures. OSFI, which has no oversight role over provincial credit unions, subsequently revised its corporate governance guidelines in 2013 and again in 2018. Federally regulated banks appear to have responded by sharpening their efforts to bring on board members with “broader skillsets and experience” and “relevant financial industry and risk management experience,” as Jeremy Rudin, then Superintendent of Financial Institutions, noted. Bank boards have also shifted their attention to strategic direction and risk management (Rudin 2016).

While governance has been a key part of the reform agenda for federal policymakers and banks, less is known about how credit unions have evolved their governance practices and standards to address the growing complexity of banking and the changes taking place in the provincial credit union sector, as well as how credit unions have performed financially during this period. This gap is not altogether surprising. Credit unions are much smaller than the chartered banks. They also have no publicly traded shares and are subject to few public disclosure requirements. As a result, credit unions generally generate far less academic, media or policy scrutiny than banks.

However, the high-profile demise of Pace Credit Union, a mid-sized southern Ontario credit union, has drawn sustained media and public attention and raised questions about the sector’s governance practices, including the quality of supervision.

Concerns about co-operative governance are not new. As co-operatives, credit unions are structured as one-member, one-vote businesses. Observers have long expressed concern, going back at least to the 1960s, about the dwindling share of members who vote at annual general meetings. A 2012 study (Goth, McKillop and Wilson) of Canadian and US credit unions, for example, found that turnout was often below 2 percent of the eligible membership, raising concerns about whether members understand that they are owners with voting and control rights and have a responsibility to monitor their organizations. The low participation rate also raises questions about board management capture, incentives and efficacy. Observers have also expressed concern about the share of voters who are employee-members, raising questions about who really controls the credit union.

If credit unions were unimportant, these observations might not matter. However, credit unions represent an important part of the Canadian banking sector and, therefore, the Canadian economy.

With these perspectives in mind, this E-Brief begins with a snapshot of the evolution and performance of the credit union sector over the 2012-2019 period, reviews the practices and board composition at some of the country’s biggest credit unions and outlines how these practices have evolved over time.

Underpinning our analysis is the idea that strong governance supports strong financial performance, though of course many factors ultimately affect the latter. Most of our analysis is focused on the largest credit unions, in part because of the relative absence of publicly available information about the wider universe of credit unions, and in part because of their weight: the 10 largest credit unions account for more than half of credit union assets. As a result, our findings do not apply to smaller or mid-sized credit unions like Pace, even though the writing of this E-Brief was inspired in part by its demise.

On performance, the available data suggest the largest credit unions have fared well over the period before the pandemic but with some important opportunities for improvement.

On governance, there have been commendable efforts to improve over this same timeframe, with boards increasingly using deliberate strategies to recruit skilled and experienced board members. Acknowledging this, we provide specific governance-related recommendations of things credit unions can do to head off existing, emerging and future challenges, especially those associated with a shifting technological, regulatory and competitive environment as well as those inherent with democratic governance in large co-operatives.

First, credit unions need to be clear about their purpose. They need to use that purpose as a guide through an increasingly difficult operating environment including future mergers, the possibility of interprovincial “passports” and whether to take up the federal credit union option. Clarity of purpose can also help credit unions assess whether any gaps in conventional performance measures (e.g., efficiency) are by accident or by design (i.e., aligned with purpose). If the latter, the board should ask management for indicators that capture those member benefits and control for those differences. If the former, with the gap due to substandard performance, the board needs to ask for a plan to fix the problem.

Second, credit unions need to be mindful of the challenges associated with more deliberate board recruitment strategies. These include a potential loss of legitimacy as democratic institutions, the absence of strong voices from non-professional walks of life and, ultimately, the risk of capture by management and a small cadre of voters.

Third, it should be easier to learn about Canada’s credit unions, and for members to hold them to account. It is elsewhere. For example, in the US the National Credit Union Administration provides easy-to-access historical financial data on credit unions going back decades. OSFI similarly makes data on the large banks available on its website, and provincial regulators should do the same for credit unions.

1. Credit Union Performance

The financial sector is critical to the Canadian economy. Through the efficient allocation of capital, it affects both absolute and relative sectoral economic growth. Given this important role, it is vital this sector be competitive – and resiliently so. Credit unions play that competitive role in Canada, with 7 percent of banking sector assets outside of Quebec and with significant market shares in BC, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

But what about performance? How have credit unions fared in the time since the Great Financial Crisis? The answer will give us a snapshot as to the health of credit unions and drive some of our thinking on where governance needs to go to keep these financial institutions competing in an increasingly complex environment.

There is little in the way of easily accessible publicly disclosed financial information for credit unions.

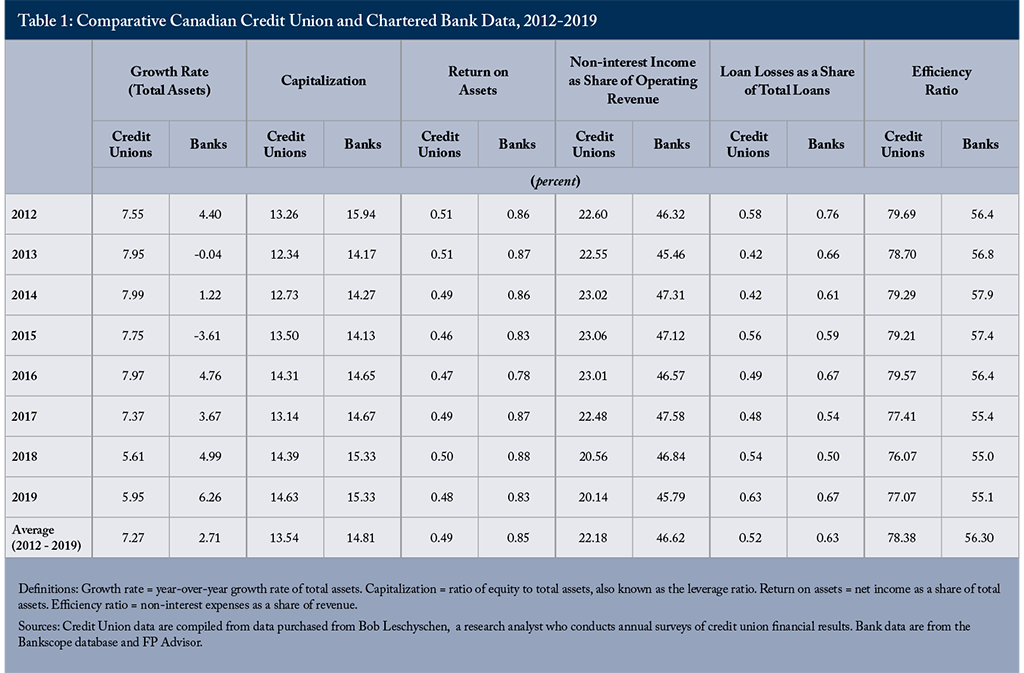

We acknowledge the period in question represents a relatively benign operating environment. Important insights can be missed when data do not capture periods of stress. With this important caveat noted, Table 1 summarizes the resulting comparative data.

These findings are consistent with those of other researchers who have found that credit unions generally do a good job of underwriting loans and have been resilient to economic shocks.

This relatively good performance of the large credit unions provides some comfort to Canadians interested in a vibrant and competitive financial services landscape. Clearly, credit unions are doing some things well.

However, Table 1 shows that there are areas where the credit unions trail the banks by significant margins. Return on assets, while stable, is well behind the banks over the period we looked at. Similarly, the efficiency ratio – as the name suggests a signal of how efficient a business is, measured as non-interest expenses as a share of revenue – is, on average, 40 percent higher than that of the banks (lower is better).

In interpreting these data, we need to be mindful of a few facts. First, a straight comparison between the efficiency ratios of banks and credit unions does not tell the whole story. Banks earn considerable fee-based revenue from investment banking operations. Credit unions have not yet operated in this area. Whether they could or should is not the subject here, but if we remove these sources of income from the bank efficiency calculations, the gap between the efficiency ratios for the banks and credit unions narrows.

Second, while credit unions universally recognize the importance of being profitable, they also stress other goals such as community impact, one of the sector’s seven co-operative principles.

There is some evidence that credit unions are delivering on these other objectives. For example, they operate large branch networks in rural and poorer parts of the country, give back a large share of their net income to communities and have consistently earned “best banking” awards in the retail and commercial markets.

Nevertheless, good governance suggests boards should demand accountability for what is driving these lower metrics and assure themselves that the credit union/bank discrepancy actually represents the pursuit of a wider range of goals, differences in business models, and investments in community benefits and not substandard performance. In particular, boards should make sure that management can clearly identify and measure these community benefits and is not hiding poor performance behind the claim that credit unions are different.

In conclusion, although the large credit unions have performed well over 2010s, credit union boards should continue to push for improvement to ensure they remain competitive and are making good on their investments in co-operative principles.

2. Governance in Credit Unions

Having analyzed the credit union performance over the last decade or so before the pandemic, we now look at how governance has evolved over this same time period.

Credit union governance is complex. Although they are much smaller than federally regulated banks, credit unions are nevertheless major business organizations, with the largest having billions of dollars in assets and thousands of employees. To provide the many services required by an increasingly diverse membership and to stay competitive in an industry being transformed by technology (e.g., fintech) and regulatory changes (e.g., data-sharing requirements), credit unions are making large investments in everything from innovative service models to new technology platforms.

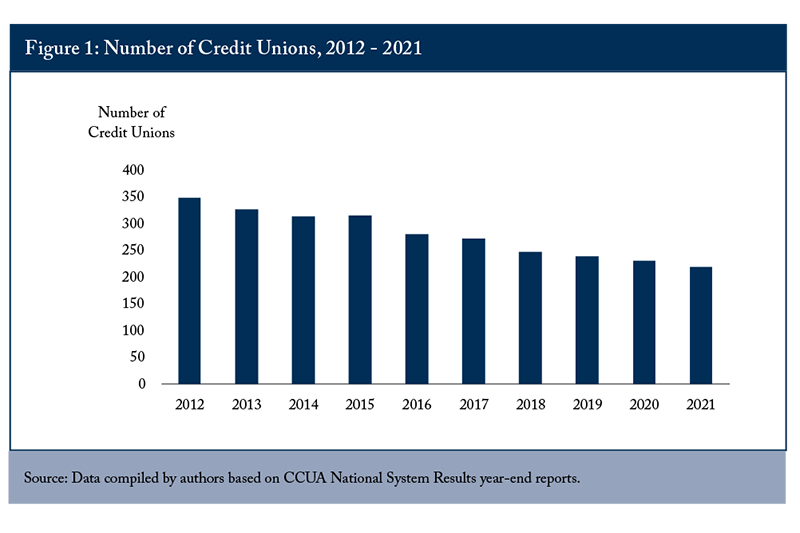

To meet these challenges, credit unions are increasingly merging. Figure 1 shows that in the last 10 years, the number of credit unions has fallen by 129, or 37 percent, to 219, well down from the post-war high of more than 3,200 in the 1960s. With two notable exceptions, there have been no new credit unions in Canada since 2000.

For larger credit unions, the pressing need is to recruit board members with experience providing governance oversight for large complex organizations operating in a competitive and highly regulated sector. The complexity of credit union governance is also linked to the credit union’s co-operative structure. As co-operatives, credit unions are democratic in nature but struggle with the reality that members do not vote in annual general meetings. Like other co-operatives, when credit unions were first established, this democratic structure initially translated into significant participation in the form of attendance at annual general meetings, voting and volunteering at the board level but also operationally. But as banking became increasingly digitized and commoditized, and as credit unions grew into larger, more sophisticated organizations, the relative importance of this participation declined.

Low membership participation rates raise concerns about possible board capture by management or special interests. Unlike publicly traded companies, there is no market for corporate control – co-operative and credit union boards are not subject to the discipline imposed by investors who accumulate shares on an exchange and have a strong incentive, through large ownership positions, to carefully monitor management and the board. At the same time, the use of strategies such as skill matrices to recruit knowledgeable, competent and experienced board members tends to result in managed and largely uncontested elections that can entrench a board and create incentives to support the status quo rather than contemplate changes (e.g., mergers) that might threaten their positions. This is a challenge with no easy answer. On the one hand, boards need to recruit skilled and experienced members who can oversee and steer complex businesses; on the other hand, the democratic principle is foundational to credit union governance and arguably the most important of the seven co-operative principles.

To understand how credit unions are grappling with this challenge, we interviewed eight individuals occupying senior governance roles (board chairs, corporate secretaries and chief governance officers) at some of the largest credit unions in the country, seven of which were among the 10 biggest. We concentrated our efforts on this group for three reasons. First, the 10 largest credit unions account for almost one-half of system assets. In Alberta, the largest credit union alone accounts for 61 percent of provincial credit union assets.

Second, if there are governance and financial challenges at the dwindling number of smaller credit unions, they are managed in much the same way that federal regulators (and, before that, the banks themselves) have managed problems at smaller banks.

Third, and finally, it would have exceeded the scope and capacity of this E-Brief to properly sample and interview representatives from the numerous, but shrinking, small to mid-sized credit unions and match those interviews with data that in many cases are simply not available to outsiders – a problem for those interested in understanding the sector.

With that in mind, our interviews found that governance personnel at the largest credit unions are keenly aware of their challenges, all of which can be traced back to the tension between needing to recruit knowledgeable, skilled and experienced board members and their democratic nature. These challenges include:

- As credit unions become larger and more complex, the importance of good governance increases dramatically. Without good governance, credit unions become dependent on both the executive team’s ability to properly manage the organization, a dependence that poses significant risk as credit union complexity increases along with the ability of the regulator to stay on top of issues – and address them in a manner proportionate to the size of the organization – before they become problems.

- As credit unions become more complex, they need board members with specific skills and experience. The democratic process, on its own, does not necessarily produce the right set of individuals.

- As boards become populated by individuals with strong professional backgrounds and experience outside the sector, credit unions are – and must remain – purpose-driven organizations. The mission of credit unions is a key part of their competitive advantage, and Canada’s credit unions must remain committed to addressing a range of issues of interest to their members.

- Traditional models of regional representation through a delegate system, while useful to accommodate mergers and expansion across different communities, can result in the election of weak board members from the delegate pool with little to no experience or expertise.

- Regulators are playing an increasingly important role in governance, especially in some provinces, by setting out governance expectations similar to those from the federal regulator, OSFI. In practice, this means regulators are looking for evidence that credit union boards are carefully managing their exposure to risk.

- The requirements imposed by federal regulators and those provincial regulators that have mimicked OSFI’s guidance most closely (Saskatchewan, BC and Ontario) are advantageous if implemented properly and if sensitive to the underlying co-operative purpose. Our interviewees generally acknowledged that there seems to be a trend toward following something like OSFI’s governance approach. Some also noted that it was good to be more or less OSFI aligned should they ever contemplate taking up the option of becoming federally incorporated.

Meanwhile, a review of the websites and annual reports of large credit unions suggests that they are increasingly adopting good governance practices by using skill matrices and other methods to bring people with the right set of abilities and experience to the board. Their boards are increasingly populated by individuals with relevant knowledge, skills, experience and advanced governance training.

But good governance is more than just attracting the right board members; it also requires that these members work together effectively. Are the board members mindful of the co-operative’s purpose when making decisions? How well do they understand the risks and the opportunities in the marketplace, given that purpose, and how effectively do they govern strategy and risk? It is critical that the board is able to set strategic and measurable key performance indicators for management that are aligned with the credit union’s purpose and that position it for long-term success. Ultimately, success in this area requires that the board not be taken captive by management who are better informed about developments in the industry.

The board can guard against capture by providing management with a set of performance indicators and attendant incentives that create an efficiently run credit union to deliver meaningful benefits for members. Management should be given incentives to run an efficient business aligned with the co-operative purpose. Similarly, board members must be given the proper incentives. Remuneration should be sufficient so that high-quality individuals will run for office. In addition, board performance should be evaluated regularly through assessments linked to the credit union’s key purposes and related financial objectives.

However, incentives alone are not enough. Large credit unions also need to use deliberate recruitment strategies to find knowledgeable, skilled and experienced board members. From our interviews, this is happening among the large credit unions. These practices, however, come with a potential cost, namely questions about democratic legitimacy, groupthink and, in a worst-case scenario, board-management collusion. While there are no easy solutions to this dilemma, staying focused on corporate purpose and giving meaningful, transparent disclosure around forward-looking key performance indicators, strategies and risk can improve member oversight and can be powerful tools to help mitigate risks.

3. Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations

The credit union sector performed well in the post-financial crisis/pre-pandemic period, albeit with some important opportunities for improvement. As was the case in the rest of the financial sector, credit union governance continued to evolve as credit unions faced the challenges found in a new economic and regulatory environment. This evolution will need to continue for credit unions to be resiliently competitive in one of the Canadian economy’s most vital sectors.

The premise of this E-Brief is that governance matters – poor governance is more likely to lead to poor performance, while good governance fosters good performance. While financial-sector policymakers and corporate leaders have tended to focus on the governance of chartered banks, credit union governance is also important. As we show, credit unions play a significant role in the financial activities of many Canadians (particularly in parts of western Canada) and hold a sizable portion of the broadly defined banking system’s assets. With that in mind, our recommendations are as follows.

First, the boards of credit unions, particularly larger ones, must be clear about their co-operative purpose as they navigate an increasingly difficult operating environment. Clarity of purpose is critical as credit union boards determine what is behind the gap between their performance and that of the banks in terms of two key measures, namely return on assets and the efficiency ratio. If the gap can be traced back to purpose and differences in business models, then the board should ask management for meaningful and measurable indicators that capture those member benefits and control for those differences. If, on the other hand, the gap is due to substandard performance and the accretion of costs that are not aligned with strategic purpose, then the board needs to ask for their management team to produce a plan to fix the problem.

Second, credit unions need to ensure that board and member dynamics are conducive to good communications. To do this, credit unions must continue their pursuit of skilled and experienced board members who are knowledgeable about the credit union and its purpose, while at the same time increasing transparency and information flow to members and encouraging meaningful member participation, engagement and evaluation. This is especially important given the challenges posed to the co-operative model by the reality of low member engagement and voter turnout.

To achieve these goals, board members should commit to do most of their business with the credit union (to ensure they understand the user relationship), there should be opportunities for the board to hear directly from member-owners as well as timely disclosure of key performance indicators to members. Credit unions could also consider term limits, board evaluations and compensation appropriate to the scale of the business, as well as structures that create incentives for directors to stay focused on overseeing productive and resilient organizations that deliver on their co-operative purpose.

Finally, it should be easier to learn about Canada’s credit unions. It is elsewhere. In the US, for example, the National Credit Union Administration provides easy-to-access historical financial data going back decades, making it relatively easy for members, researchers and other regulators to study and, where appropriate, hold a credit union to account. OSFI similarly makes data on the large banks available on its website. There is an opportunity for provincial regulators to do the same for credit unions. This would not only make it easier for members to hold their credit unions to account,

References

Abacus Data and Co-operatives and Mutuals Canada. 2020. “Co-operatives and Mutuals in an Age of Uncertainty: Survey Findings.” Available at: https://canada.coop/sites/canada.coop/files/research_results_en_final.pdf.

Aguilera, R. V., C. Florackis, and H. Kim. 2016. “Advancing the Corporate Governance Research Agenda.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(3), 172-180. May.

Bank for International Settlements. 2017. Finalizing Basel III: In Brief. Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d424_inbrief.pdf.

_________. 2017. Basel III Summary Table. Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3/b3_bank_sup_reforms.pdf.

Bradshaw, James. 2021. “Ontario’s financial regulator puts struggling PACE credit union up for sale, sources say.” Globe and Mail. June 2. Available at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-ontarios-financial-regulator-puts-struggling-pace-credit-union-up-for/.

Canada. 1964. Report of the Royal Commission on Banking and Finance. Ottawa.

Canadian Credit Union Association (CCUA). 2021. Top 100 Report, Second Quarter 2021. Available at: https://ccua.com/app/uploads/private-files/top100-2Q21_15-Sep-21-1.pdf.

_________. Community & Economic 2019-20 Impact Report. 2020. Available at: https://ccua.com/app/uploads/private-files/2019-20_Impact_ReportENG_DIGITAL_FF.pdf.

_________. 2021. “Canada’s Credit Unions Continue to Set a Longstanding Record with Five 2021 Ipsos Financial Service Excellence Awards Wins.” October 7. Available at: https://ccua.com/news/canadas-credit-unions-continue-to-set-a-longstanding-record-with-five-2021-ipsos-financial-service-excellence-awards-wins.

Conger, J.A., D. Finegold, and E.E. Lawler III.1998. “Appraising boardroom performance.” Harvard Business Review 76(1): 136-149.

Cook, M. L. 1995. “The Future of U.S. Agricultural Cooperatives: A Neo-Institutional Approach.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 77(5): 1153–1159. December.

Forbes, D.P., and F.J. Milliken. 1999. “Cognition and corporate governance: Understanding boards of directors as strategic decision-making groups.” Academy of Management Review 24 (3): 489–505. July.

Goth, P., D. McKillop, and J. Wilson. 2012. Corporate Governance in Canadian and U.S. Credit Unions. Filene Research Institute Report. Available at: https://filene.org/learn-something/reports/corp_governance.

Hansman, Henry. 1999. “Cooperative Firms in Theory and Practice.” Finnish Journal of Business Economics. January.

Hermalin, Benjamin E., and Michael S Weisbach. 1988. “Endogenously Chosen Boards of Directors and Their Monitoring of the CEO.” American Economic Review 88 (1): 96-118. March.

Higgins, Mike. 2016. “Financial Soundness of Canadian Credit Unions.” Filene Research Institute Report No. 394.

Hoel, Robert F. 2011. “Power and Governance: Who Really Owns Credit Unions?” Filene Research Institute. Filene Research Institute Governance Series.

Kalmi, Panu. 2007. “The disappearance of cooperatives from economic textbooks.” Cambridge Journal of Economics. 31: 625-647. July.

Losier, David. 2021. A Passport to Success: How Credit Unions Can Adapt to the Urgent Challenges They Face. Commentary 610. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. November.

Maiorano, J, Laurie Mook, and Jack Quarter. 2016. “Is There a Credit Union Difference?” Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research. 7(2): 40-56.

MacInsoh, R. 1991. Different Drummers: Banking and Politics in Canada. Toronto: MacMillan Canada.

Manning, Christopher D., Prabhakar Raghavan, and Hinrich Schutze. 2008. Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge University Press.

Nitani, M., and N. Legendre. 2021. “Cooperative lenders and the performance of small business loans.” Journal of Banking & Finance. 128: 106125. July.

Powell, Art. 1979. “Making Democratic Control a Reality: A Continuing Task for System Leaders.” Credit Union Way. Volume 32.

Rudin, Jeremy. 2016. “Enabling More Effective Governance of Canadian Financial Institutions: Remarks to the Global Risk Institute.” June 14.

Schiehll, E., and H.C. Martins. 2016. “Cross-national governance research: A systematic review and assessment.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24: 000–0. January.

Srivastav, A., and J. Hagendorff. 2015. “Corporate governance and bank risk-taking.” Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24: 334–345. August.