Executive Summary

Public-sector investment funds (especially pension funds) have been increasingly pooled and managed by investment management firms in Ontario. Pooled asset management generates a net benefit to public-sector spending patterns by realizing benefits from economies of scale, including reducing costs associated with the duplication of fund management while also enhancing risk management. However, a focus on pooling public-sector pensions has meant that the possibility of consolidating other public-sector assets, like municipal cash reserves, has received less attention.

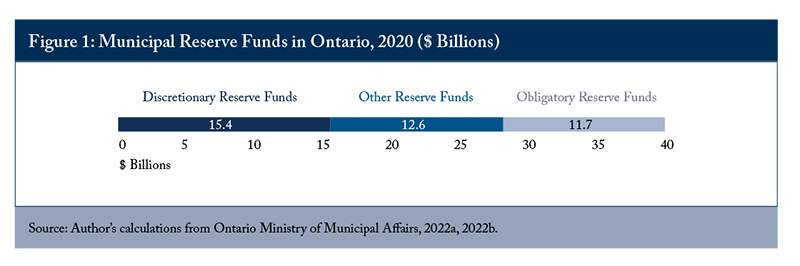

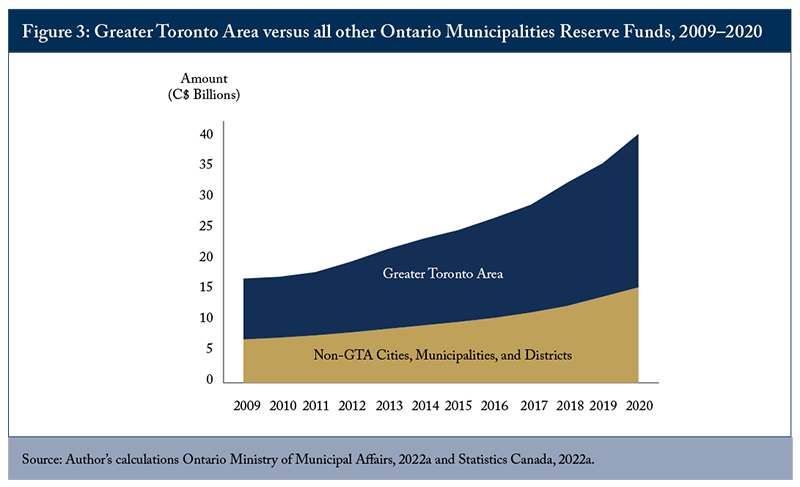

Ontario’s local governments are accumulating significant liquidity reserves. Municipal reserves come in various forms, each symbolizing a distinct savings category. This report’s calculations show that in 2020, Ontario municipalities, counties, districts and cities held $39.7 billion in reserve funds. In the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), excess municipal reserves coincide with population and housing growth rates, while some non-GTA areas have also accrued substantial holdings. Occasionally, these savings are held in cash and equivalents. This study finds that local governments collectively held $20.1 billion in cash and temporary investments in 2020.

The growth of municipal reserves and cash balances raises questions about how best to manage and utilize these funds. The point is not that municipalities are mismanaging their reserves and cash holdings. Instead, this report suggests that Ontario’s local governments could collectively benefit from pooling these reserves and cash holdings. One just needs to look at recent municipal investments as proof. In 2020, municipalities earned a return of just greater than 2 percent on their reserves through interest and investment income.

Clearly, cities could be getting better investment returns. One potential solution is improving the coordination between local governments and Ontario’s public-asset management institutions such as ONE Investment and the Investment Management Corporation of Ontario (IMCO). Both are knowledgeable about municipal needs, consolidating public funds and dispersing investment returns.

To implement better pooling and higher-return investments for municipal government, the Ontario government should consider legislative changes to the Municipal Act and Development Charges Act to remove limits on investment durations and improve clarity on investment pooling. With careful planning and collaboration among municipal governments, the province and other agencies, the consolidating of public funds in Ontario can benefit local governments, public agencies and the communities they serve.

The author thanks Benjamin Dachis for his guidance and insights, as well as Alexandre Laurin, Andrew Sancton and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft. The author retains responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Introduction

There is a long history of investment managers supporting the supervision and investment of public funds in Ontario. Beginning with the Ontario Pension Board in 1920 and quickening through the 1980s, public-sector pension and non-pension funds have been increasingly pooled by investment management firms to provide increased revenue for public coffers while reducing the costs associated with the duplication of administrative services. Under this pooling approach, different organizations’ funds are comingled and overseen by an investment management firm that administers financial portfolios corresponding to each member’s budgetary goals. In turn, each contributing agency owns a share of total portfolio assets and receives a return dependent on full portfolio returns.

In Ontario, public-sector pensions have been the principal target for pooling investment portfolios. By the summer of 2022, six major Ontario public pension plans – who are major global players in capital markets – managed approximately a half trillion dollars in assets.

Certainly, various other public cash and revenue streams can be pooled to provide an investment return on government funds. These public-sector non-pension funds are typically linked to local governments’ spending goals outlined in their operating and capital budgets. To be clear, these funds have different goals than pooled pensions. Unlike pensions, which provide longer-term support for contributors, the demands of non-pension funds require that any pooled investments are easily accessible for the cash-flow needs of local governments and public-sector agencies.

For local governments, effective asset management is essential for making timely investments that optimize the repair and rehabilitation costs of capital assets. This strategy involves considering various factors such as market trends, environmental assessments, other capital project timelines and grant funding from different levels of government, among others. Unlike for pension funds, the investment strategies for these funds must be carefully tailored to the unique circumstances of each situation. They cannot simply rely on a “set it and forget it” approach.

Local government investment pools (LGIPs) are one investment vehicle that has successfully risen to the challenge of supporting local government needs. Compared to pensions that may hold assets with long maturities, LGIPs allow local governments and public agencies to combine their funds to invest in highly liquid financial instruments such as money-market funds and short-duration government bonds, which allow local governments and public agencies to quickly access cash. These investment pools are similar to bank accounts in the ease of cash withdrawals, ensuring local governments can access the funds needed to meet their daily financial obligations and cash flow needs.

As an added benefit, LGIPs enable local governments and public agencies to consolidate their resources and invest in a broader range of assets, potentially yielding increased returns and providing greater investment portfolio stability. Still, local government investment pools are not without risk. Critics of fund consolidation contend that they can expose local governments and public agencies to market instability, legal challenges related to account transparency and political issues related to fund privatization.

Additionally, investment pools are vulnerable to the same market risks as any other investment vehicle since they often invest in various financial securities (Maynard 1989). Any attempt to consolidate investments must consider municipalities’ duration requirements and financing needs while acknowledging that public officials aim to avoid public scrutiny due to investment losses.

Given the existence of Ontario’s municipal reserves, the benefits of pooling public assets and a provincial climate increasingly friendly to pooling public-sector funds, this Working Paper asks two questions. First, to what extent have Ontario’s local government reserves and cash holdings grown over time? Second, could these reserves and cash holdings be better managed to benefit municipalities and their residents? To answer these questions, this report analyzes public data available through the Government of Ontario’s Financial Information Return portal.

The report begins by making a case for pooling, consolidating and investing unmanaged public funds. It reviews the benefits associated with consolidation before detailing the political and legal landscape surrounding the investment of public funds in Ontario. Next, the report examines local governments and the apparent increase in their reserves and cash holdings.

This focus is supported by the detailed and transparent information in the Financial Information Return portal, making municipalities a suitable example of government entities with substantial funds. The report identifies the different pots of local government funds in Ontario comprising the $39.7 billion.

This report’s focus on the obligatory reserve funds associated with development charges warrants an explanation. Over the past year, the reserves related to development charges have been the focus of increasing debate given the passing of Bill 23, the More Homes Built Faster Act, which received Royal Assent on November 28, 2022. Bill 23 made several amendments to the Development Charges Act (1997), such as removing housing services from development charges, providing exemptions for affordable and attainable housing, altering the method for determining development charges, and extending the by-law expiration period from five to ten years. The bill also includes provisions for rental housing development charge reductions, a maximum interest rate, and a requirement for municipalities to spend or allocate 60 percent of reserve funds annually for certain services. Municipalities were critical of these changes. However, the Government of Ontario was adamant. A Nov. 30, 2022, letter from Municipal Affairs and Housing Minister Steve Clark to both the mayor of Toronto and the President of the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) was critical of “out-of-control municipal fees” and taxes associated with new homes. The letter outlines a 2023 third-party audit of municipal finances, particularly reserve funds and development charge administration.

This report aims to contribute to this conversation. It is understood that development charges are necessary. However, the goal should be to target development charges to only where they are necessary. Associated investment returns can offset their continued growth, but collecting investment returns should not be an explicit goal of development charge policies. Accordingly, we caution against an overreliance on the investment returns associated with public-fund consolidation for generating municipal income. Development charges should not be habitually collected to generate investment returns, especially if these charges are excessive or unnecessary for supporting growth and other needed infrastructure.

As well, this $39.7 billion in local government funds warrants further consideration through inter-organization research committees and legislative clarification regarding the potential consolidation of reserves associated with development fees, all while focusing on the largest municipalities that are the primary sites of reserve funds.

Ontario’s Municipal Act limits investment durations for these development-charge monies to short-term, fully liquid investments. Part of the reason for these limits relates to local governments’ cash flow needs. Any approach to public-fund consolidation must recognize that local governments require a certain level of liquidity to quickly convert assets into cash for operating and capital expenses. Therefore, the entire $39.7 billion is not simply available for long-term investments.

Managing these municipal funds differs from the more common approaches to pooling pension funds. Asset management is essential for making timely investments that optimize repair and rehabilitation costs of capital assets, but this requires considering factors such as market trends, environmental assessments, project timelines and grant funding from other levels of government, among others. Furthermore, local governments require that consolidated funds remain safe so that they can continue supporting their constituents.

Poor investment decisions must not impede local governments’ effective functioning. There are examples of public fund pools failing in US jurisdictions through the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is paramount that any approach to pooling public funds maximizes returns while managing an acceptable level of risk. Fortunately, Ontario already has agencies and legislative frameworks that can help. Both ONE Investment and the Investment Management Corporation of Ontario (IMCO) offer investment options that meet these requirements, and the Municipal Act’s prudent investment standards provide a robust regulatory framework for local government investment practices.

Any effort to pool public funds requires a two-pronged approach. First, the Ontario Municipal Act needs legislative clarification of Part XIII, Debt and Investments, Sections 418 and 418(1). The amended legislation could further detail local governments’ ability to pool their cash and temporary investments, discretionary reserve funds and obligatory reserve funds associated with development charges. Meanwhile, the Development Charges Act could clarify the extent to which associated funds can be invested in local government investment pools.

Secondly, a fruitful path toward public-fund consolidation requires a partnership among stakeholders. In the case of local government funds, this collaboration includes the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, the AMO, the Municipal Finance Officers’ Association of Ontario, the Investment Management Corporation of Ontario, ONE Investment, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), and the Government Finance Officers Association, among others. With a clear understanding of the current funding model, careful planning and collaboration, consolidating public funds in Ontario can benefit local governments, public agencies and the communities they serve.

Local Government Investment Pools (LGIPs)

By the end of 2021, more than $80 billion in public-sector funds were being administered by investment managers in Ontario.

Since the late 1980s, researchers have suggested that pooling public funds can provide several benefits for local governments, public agencies and the communities they serve. Access to financial markets, resources and investment possibilities may not be as readily available to smaller municipalities as to larger ones. According to Schedule 61 from Ontario’s 2020 Financial Information Return, local governments earned a return of just more than 2 percent on their reserves through interest and investment income. Consequently, fund consolidation allows smaller public-sector agencies to cooperate and access larger investment markets by realizing economies of scale with pooled cash balances (Nukpezah 2018). In turn, local governments and public agencies gain from the knowledge of competent asset managers who can assist them in making well-informed investment decisions and minimizing investment risk.

Realizing economies of scale lowers management costs and reduces the duplication of services. Pooling can also reduce investing fees and other expenses for local governments, which is particularly advantageous for smaller municipalities with limited financial resources. In turn, these economies of scale are most helpful when funds are commingled with other government assets rather than held in smaller accounts, thereby allowing the purchase of assets with longer maturities (Thompson 1988, Bland, Nukpezah, and Shinkle 2015). Comingled funds earn higher returns for local governments and public agencies since asset managers can invest in a broader range of securities to construct diverse portfolios, such as purchasing higher-yielding, higher-denomination financial instruments (Thompson 1988).

Financial gains are also the result of employing full-time asset managers who can enhance risk management during fiscal crises (Modlin 2016). Indeed, risk management is a crucial component of consolidating and managing public funds. In this regard, funds are often directed toward non-volatile instruments because investors have a fiduciary need to manage public funds safely (McCue 2000, Kim 2016). In sum, pooling public funds for investment can assist in safeguarding public money and ensuring its effective and efficient usage.

There are several approaches to pooling or consolidating public funds. Most typically, these pools are managed by government agencies or state-owned enterprises. For example, the treasury department of a larger regional government can construct and administer state-sponsored LGIPs (Cook and Duffield 1998). Arm’s-length entities may manage public fund portfolios, or they may be managed entirely by private entities or non-profit organizations (Davis and Walker 1997, Bovaird 2016). Elsewhere, more junior governments and public agencies may craft inter-local agreements allowing them to pool and invest their cash holdings in various financial instruments (Nukpezah 2018). Sometimes, these bodies consolidate their funds into a single account, which a professional investment manager or a financial institution can manage. In sum, the demands of local governments and public agencies will ultimately determine how they approach pooling or consolidating public funds.

Fulfilling the needs of local governments and public agencies is central to any effort to consolidate public funds. LGIPs attract public-sector investors when they provide strong and steady returns, thereby helping them navigate continual budgetary constraints (Bland, Nukpezah, and Shinkle 2015). Local government and public agencies also need to be reassured that consolidated funds are safe so that they may continue to support their constituents. Clearly, public officials have no desire to face public scrutiny over funds lost from poor investment decisions. For this reason, pooled funds need to maximize their overall returns with an acceptable level of risk (Markowitz 1952). Interestingly, government agencies can cope with market uncertainty better than private investors (Hochrainer and Mechler 2011).

Lastly, any approach to consolidating public funds must support local governments’ and public agencies’ cash-flow needs. Local government and public agencies must maintain a certain level of liquidity, understood as their ability to convert assets quickly to cash to pay for operating and capital expenses. For this reason, portfolio management strategies of pooled funds work to match the maturity dates of fixed-income holdings with the cash flow needs of their public-sector contributors (Thompson 1988, Maynard 1989).

Clearly, there are risks associated with local government investment pools. Some critics claim that fund consolidation can expose local governments and public agencies to risks and expenses related to market instability, legal challenges pertaining to account transparency and political interference in investment strategies. Investment pools are also vulnerable to the same market dangers as any other investment vehicle since they frequently invest in various financial securities (Maynard 1989).

Comparing Pooling Practices in Local Governments Worldwide

LGIPs are a widely utilized investment tool in the US, and are designed to provide state and local governments with a means to invest their funds efficiently. S&P Global Ratings tracks 74 US LGIPs with total assets under management of nearly US$400 billion. Despite their varying sizes, ranging from the Pennsylvania INVEST Community Pool managing just US$62 million to the massive State of Texas US$69 billion Treasury Pool, the average assets under LGIP management is some US$5.4 billion. In September 2022, these LGIPs generated an average seven-day yield of 2.54 percent invested in repurchase agreements (24.22 percent), bank deposits (18.18 percent), commercial paper (16.34 percent), government agency bonds (14.43 percent), treasuries (9.89 percent), asset-backed securities (8.58 percent), money-market funds (4.23 percent), corporate bonds (3.69 percent) and municipal debt (0.44 percent), with a weighted average maturity of 55 days.

While LGIPs have provided stable returns for US local governments, some have failed in the past. For example, in 1987 a West Virginia LGIP lost US$279 million, while the Orange County California fund filed for bankruptcy in 1994 after losing more than US$1.7 billion by investing in derivatives (Hayes 1999, Lynch, Shamsub, and Onwujuba 2002, Nukpezah 2022). As a result, some states have implemented stricter regulations and investment guidelines to prevent similar incidents from happening again.

Fewer LGIPs have been established outside North America. Instead, pooled financing mechanisms and subnational pooled financing mechanisms let local governments pool their borrowing requirements rather than their savings. The Local Government Funding Agency in New Zealand pools the borrowing needs of local governments to access cheaper borrowing costs, and in the UK the Local Government Association launched a Municipal Bonds Agency in 2014 that allows local governments to pool their borrowing requirements and issue bonds to the capital markets.

Meanwhile, Australia’s Victorian Funds Management Corporation provides investment management services to the State of Victoria and its public-sector entities, including 31 public authorities and local governments. The corporation is a pooled investment vehicle that invests in various asset classes, including cash, fixed income and equities to achieve long-term solid investment returns. Its website provides detailed information about the corporation’s investment objectives, performance and portfolio holdings, as well as the management and governance of the fund.

In Canada, LGIPs are less frequently deployed than in the US. However, some provinces offer unique programs tailored to the investment needs of municipalities and broader public-sector, non-pension funds. For instance, the BC Municipal Finance Authority provides access to five fixed-income investment portfolios that cater to various investment horizons. These include a money-market fund and a government-focused ultra-short bond fund for investments of up to 24 months, a short-term bond fund and fossil-fuel-free short-term bond fund for assets ranging from two-to-five years, a mortgage fund for investments of three years or more and a diversified multi-asset class fund for long-term investments of 10 years or more.

In Alberta, the Alberta Investment Management Corporation manages the Heritage Fund, a long-term savings fund that invests in globally diversified portfolios to support essential government programs. The fund’s earnings support government programs necessary to Albertans, such as health care, education and infrastructure. Saskatchewan's Association of Rural Municipalities has partnered with CIBC Commercial Banking to offer a pooled high-interest savings account that allows members to earn competitive interest rates while maintaining flexibility to move their money at any time without penalty, regardless of the amount invested. Any plans to consolidate local government funds in Ontario should consider other consolidation approaches across Canada.

Local Government Investment Pools in Ontario: Current Landscape and Future Opportunities

Ontario’s investment and legal landscape increasingly favours a consolidated approach for municipal fund management. Two public asset managers have the expertise and knowledge to help local governments make informed decisions regarding consolidating public funds. ONE Investment, a not-for-profit organization established in 1993 from a partnership between AMO and the Municipal Finance Officers’ Association, offers a suite of fixed-income and equity funds. ONE Investment can commingle public-sector funds from municipalities, public hospitals, Ontario universities and colleges, school boards and other associated organizations, enabling economies of scale in its investment activities and competitive returns. Since 1993, ONE Investment has been offering municipalities fully Municipal Act-compliant fixed-income comingled products, which expanded in 2007 to include corporate bonds and Canadian equity comingled funds in response to regulatory changes. In 2015, ONE Investment launched its High Interest Savings Account, which offers reasonable interest rates, no service charges, no minimum or maximum balance requirements and online account access, all while the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation covers deposits. ONE Investment continues to innovate and meet the changing regulatory landscape; in 2020, it launched a joint investment board and began offering global bonds and equities as part of its investment products.

The Investment Management Corporation of Ontario Act, introduced in 2015, aimed to create a new, centralized investment management entity for Ontario’s broader public sector. The act established the corporation as an arm’s length non-profit public corporation to provide investment management and advisory services to various public-sector agencies, including Crown agencies and boards, universities and municipalities. In 2017, the Investment Management Corporation (IMCO) began managing client funds for both the Ontario Pension Board and the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and later began working with the Ontario Provincial Judges’ Pension Plan. Its investment strategies include various asset classes, such as public and private equity, fixed income, real estate, infrastructure and absolute-return strategies. IMCO had $79 billion in assets as of Dec. 31, 2021.

However, while the act allowed for consolidation of public funds, MUSH-sector organizations are not legally required to be part of IMCO. Instead, many public-sector organizations continue to manage their own cash holdings in a context where provincial rules have historically deterred these agencies from investing their cash holdings. As such, while IMCO presents a viable investment management option for some public-sector organizations, others still prefer to manage their own funds.

For their part, Ontario’s local governments have experienced significant restructuring since the 1960s, potentially leading to some of the highest average populations of local governments in North America. The restructuring aimed to improve administrative capacity, including managing municipal funds. But a back-of-a-napkin accounting from Ontario’s Financial Information Return portal raises questions about municipalities’ investment successes. In 2020, local governments earned a return of just more than 2 percent on their reserves through interest and investment income.

Still, some larger municipalities with sufficient scale and debt programs may not benefit significantly from pooling as their holdings generate significant leverage and negotiating power. These municipalities may have the necessary qualified staff to run sophisticated fixed-income programs, and Ontario’s largest cities may be able to manage these funds as expertly as any pooled authority. For example, the 2006 City of Toronto Act was enacted to provide the city with greater autonomy and flexibility in managing its investments, including investing its cash holdings and managing its debt within the confines of provincial regulations. The Toronto Investment Board manages various investments for the city and in 2020 reported earning a 4.1 percent return on its long-term investments, a 1.3 percent return on its short-term investments and 2.4 percent on its sinking funds, resulting in a total of $219.3 million. However, not all Ontario municipalities have the same capacity as Toronto. It is essential to consider the benefits and drawbacks of each investment option before deciding on the management of public funds. In contrast, a mature provincial-wide fund, the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan, earned a total fund return of 8.6 percent in 2020.

In Ontario, public-sector fund consolidation is principally governed by the Municipal Act and the Financial Administration Act. These acts control how local governments can spend and outline the governance, transparency and accountability related to the investment of public funds. Section 418 of the Municipal Act details how municipalities can invest funds that are not immediately required, provided that they can be retrieved when local governments need the dollars. Said differently, the act limits investments to short-term or liquid securities. As well, municipalities cannot invest more than 25 percent of their funds at any time. They can invest capital associated with i) sinking, retirement and reserve funds, ii) funds collected or received to settle a municipality’s debt or associated interest on debt, and iii) the earnings associated with selling, lending or investing in debentures. While municipalities can combine money from different funds for investment, the interest earned from any investments cannot be used for general spending but must be proportionally returned to their source funds.

Local governments and public agencies may be limited to a list of prescribed investments as a matter of risk reduction. For example, Agricorp’s Production Insurance Program can only invest in guaranteed investment certificates. The legislation also clarifies how investments can occur. In the case of the Municipal Act, the pre-Prudent legislation associated with Part I of O. Reg 438/97L outlines what Canadian-dollar public and corporate fixed-income securities, money-market instruments and types of stocks local governments can invest in, all of which are required to have been rated as high quality by credit rating agencies and meet particular maturity requirements.

Meanwhile, recent legislative changes have allowed local governments and public organizations to benefit from advances in portfolio management. In January 2019, the Government of Ontario enabled municipalities to manage their investment funds similarly to more senior levels of government, even allowing for the combined investments of funds from different sources. Section 418.1 of the Ontario Municipal Act and Part II of O. Reg 438/97L Eligible Investments, Related Financial Agreements and Prudent Investment allows Ontario municipalities to invest public funds that are not immediately required. According to this prudent investor regime, trustees of investment portfolios must invest assets reasonably, ensure public funds’ sustainability and consider public agencies’ needs and circumstances. Investment diversification, risk avoidance and portfolio monitoring are required under the prudent investor regime. The result is that Section 418.1 expands municipalities’ investment powers by allowing public funds to be invested in a diverse array of asset classes, including real estate and private equity.

Municipalities must consider several factors to be eligible to join the prudent investor regime. Firstly, general economic conditions and the possible impact of inflation or deflation should be taken into account. Secondly, each investment or course of action should be evaluated regarding its role within the municipality’s overall investment strategy. Thirdly, the expected total return from income and capital appreciation should be assessed. Additionally, the municipality’s requirements for liquidity, regularity of income and preservation or appreciation of capital should be studied when making investment decisions. By considering these factors, local governments can make informed investment decisions that align with their financial goals and objectives.

Municipal requirements for the prudent investor regime understandably impact the extent of fund consolidation in Ontario. Municipalities must establish an investment board and fulfill specific criteria, such as having investible assets worth at least $100 million or net financial assets of $50 million. It’s worth noting that only a small percentage of municipalities, approximately 10-to-15 percent, can meet these requirements independently. Few local governments in Ontario have joined this new regime outside of Toronto, Ottawa, Thunder Bay, Kenora and several others (Kaufman 2022, Porter 2022).

However, there is reason for optimism. The prudent investment regime allows smaller municipalities to pool their investments provided they have a combined total of at least $100 million. And while the above legislation provides a solid basis for understanding municipal investment, public agencies and local governments can have difficulty interpreting their investment capabilities. For these reasons, there is a need for further legislative clarity, standardization and knowledge-sharing about local governments’ ability to pool funds. Put plainly, the potential growth of funds in Ontario, some of which are unmanaged, requires us to carefully plan and consider what to do with these reserves and cash holdings. For these reasons, this report now examines the growth of municipal funds in Ontario.

The Case for Pooling Municipal Reserve Funds

On Nov. 28, 2022, Ontario passed Bill 23, the so-called More Homes Built Faster Act.

Municipal officials quickly criticized Bill 23 for reducing their ability to collect revenue. Toronto Mayor John Tory cautioned that the new act “could cost Toronto some $2 billion over the next decade” (The Canadian Press 2020), while the AMO argued that it would cost municipalities “approximately $1 billion annually in revenue (AMO 2022).” For its part, the province was adamant that Bill 23 would reduce the cost of bringing new housing supplies to market. Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing Steve Clark wrote both Tory and AMO’s president saying the province would not waiver on restraining “out-of-control municipal fees” and that municipalities should have “no funding shortfall…provided that municipalities are achieving and exceeding their housing pledge levels and growth targets.” Interestingly, the debate surrounding Bill 23 has spotlighted two seldom-discussed aspects of municipal finance: development charges and reserve funds.

Development charges are the discretionary fees municipalities collect from homebuilders and property developers during the construction of new-build developments and some renovations

While not the primary source of capital infrastructure investments, development charges are an important financing tool for Ontario municipalities, separate from user fees and property taxes. Both Toronto and the AMO allude to this aspect in their opposition to Bill 23. Municipalities use the charges as a segregated cost-recovery approach that separates growth-related capital costs from user fees and property taxes. The fees are calculated based on the estimated cost of providing the necessary infrastructure and services to support the development. They are typically imposed as a fixed fee per unit of development (e.g., per residential unit or square footage of commercial space). The charges are typically calculated when the site plan or zoning application is submitted and remain frozen for two years after the approval of development applications, although this process differs for subdivision developments. Many municipalities collect them before or after building permit issuance. Development charge amounts can also vary depending on where the prospective developments occur (central vs. outer municipal limits) and the type of development proposed (e.g., apartments, condos, single-family dwellings or commercial properties).

Development charges have provided a stable fee collection system for Ontario’s cities, districts, counties and municipalities. They are governed by the 1997 Development Charges Act (DCA) and its associated regulation (O. Reg. 82/98), which provide the framework for local governments’ imposition and collection of the charges. This act seeks to “pay for increased capital costs required because of increased needs for services arising from development.” It enables municipalities to enact bylaws to craft their own specific development charges, which can be levied by upper, lower and single-tier municipal governments. According to the act, local governments must justify specific development charges with a background case study before passing them as bylaws.

The act provides for calculating the charges and establishes the conditions under which they can be imposed and collected. Typically, renovations to existing residential and commercial properties do not require development charges, whereas new builds do. The act also provides for appeals by developers and oversight and regulation by the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Additionally, the act requires local governments to prepare and adopt development charge bylaws that outline the specific rates and policies that apply in their communities.

The varied landscape of development charges across Ontario stems from their discretionary and jurisdictional nature. Municipalities can independently choose how much fees should be, what elements are charged and how the funds are spent. For example, Toronto has embraced development charges as a funding model with fees of $87,299 for a single-family home in 2020, rising from $45,000 in 2012. Meanwhile, some smaller Ontario rural municipalities bypass the charges as financing tools. Nevertheless, the total charges collected in Ontario are massive. In 2021, property developers paid almost $3.3 billion in charges to Ontario municipalities, rising from nearly $2.5 billion in 2019. These amounts primarily come from fees related to supporting roads, water and wastewater services.

There are ongoing debates and discussions about the appropriate use and extent of these fees. Some political leaders, pundits and academics argue that they are a vital tool for local governments to finance the infrastructure and services needed to support new development and help ensure that growth costs are fairly shared between new growth and established property owners. Municipalities frame development charges as a means of paying for capital spending while supplementing property taxes and user fees to ensure that growth-related capital costs are fully recovered from development. They see them as a robust cost-recovery tool enabling sharing of cost burdens between municipalities and developers. Indeed, Found (2019) explains that the initial capital investment is the primary cost associated with extending these new municipal developments instead of renewal or reinvestment. Others have expressed concerns about the charges’ potential impact on housing affordability and the development industry’s competitiveness and have called for reforms to the system. Dachis (2018) explains that one of the issues related to the large cash surpluses associated with development charges is that they are not always spent expediently.

How Are Development Charges and Reserves Held in Ontario?

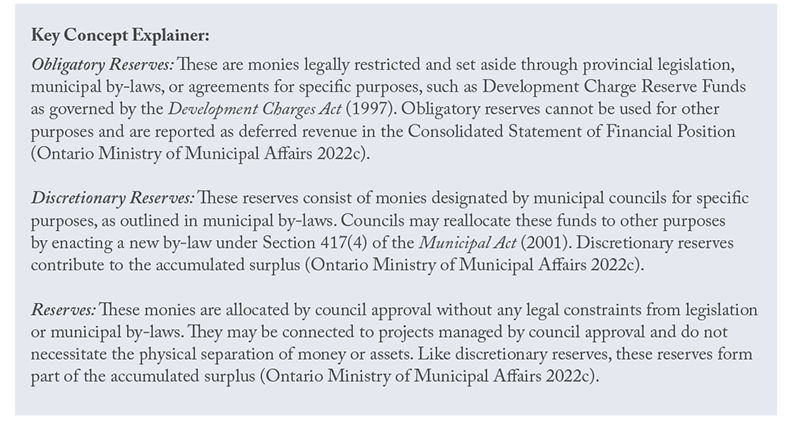

Efforts to consolidate local government assets must consider how development charges are collected and the breakdown of different municipal reserves. After collection from property managers and developers, the charges are held within obligatory reserve accounts. These accounts must be put aside for a specific purpose. Adding further complication, obligatory reserves must go into 24 different lines in Schedule 61 associated with various services, with the idea that development charges are directed to specific costs. Beginning in 2023, Section 35 (2) of the Development Charges Act requires municipalities to spend or allocate a minimum of 60 percent of a reserve fund’s balance in the following year for water, waste and highway services.

There are also two other types of municipal reserve funds that vary in flexibility. Discretionary reserve accounts include funds available for use as a municipality sees fit. Another account is other reserve funds, which may consist of capital retained for specific projects or programs.

Accounting requirements make it difficult for local governments to redirect obligatory, discretionary and other reserve funds. On the one hand, municipalities cannot simply shift reserves to general spending. The Development Charges Act specifies that obligatory reserves cannot be forwarded to municipalities’ capital accounts for unrelated expenditures. On the other hand, municipalities can borrow from reserve funds provided they repay any borrowings with interest at least equal to the minimum interest rate. For example, Section 36 of the act specifies how municipalities can borrow money from a reserve fund. Less certain is the extent to which existing legislation allows local governments to pool and invest their reserve funds. It is a question that gains importance given the continued expansion of local government reserves, raising the question of what should be done with these reserves and other cash holdings.

Results: The Extent of Reserve Funds in Ontario

To investigate the potential for pooling public assets, it is necessary to first examine the growth in reserve funds to capture the current state of these combined amounts. This report determined the extent of local governments’ reserve funds by examining publicly available financial statements from 2009 to 2020. Ontario’s cities, districts, counties and regional municipalities submit a record of their finances to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs each year. These records detail municipal discretionary, obligatory and other reserve funds.

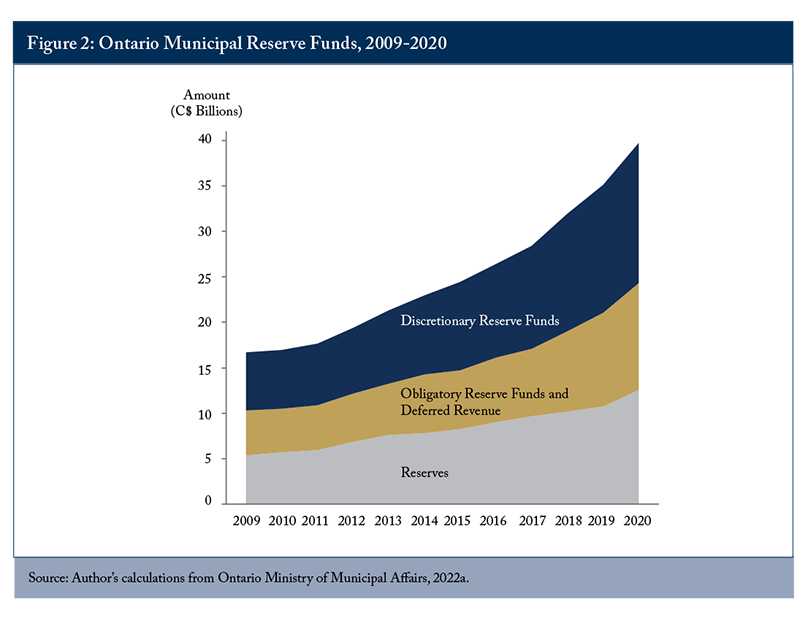

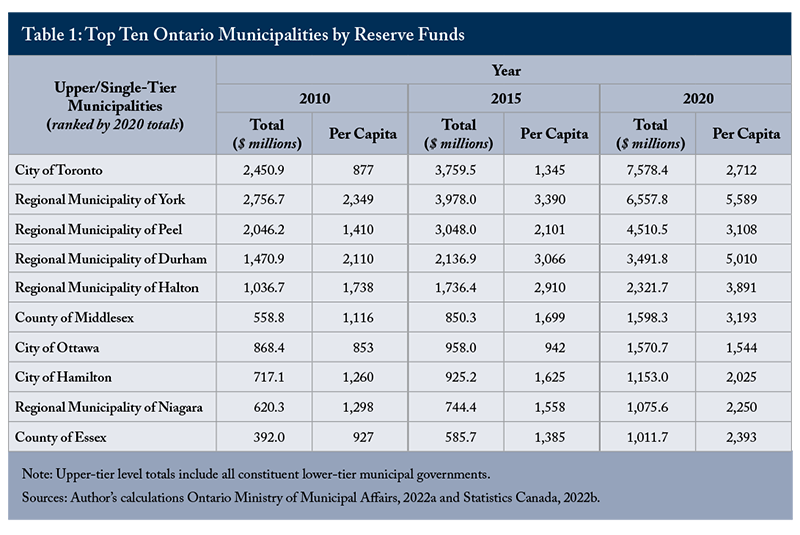

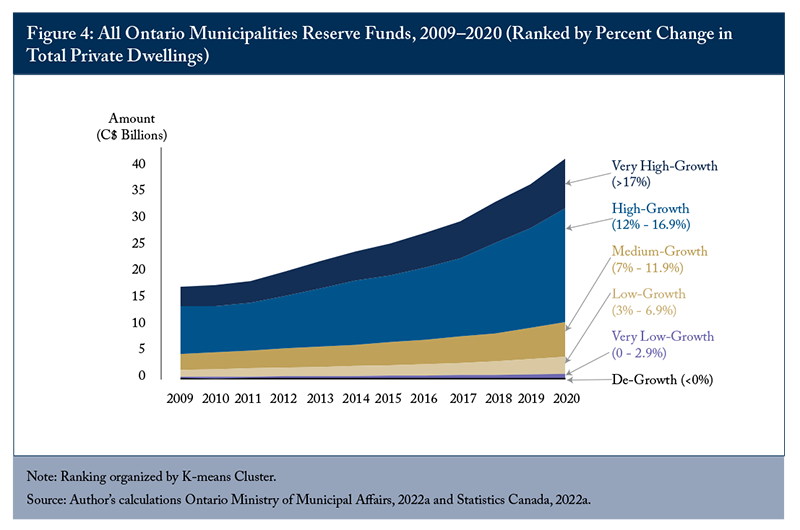

By 2020, municipal reserves reached $39.7 billion, growing 138 percent from $16.7 billion in 2009. Figure 2 shows that there has been a steady increase in all three reserve fund accounts. In 2020, Ontario municipalities, counties, districts and cities held $15.4 billion in discretionary reserve funds, $12.6 billion in other reserves and $11.7 billion in obligatory reserve funds associated with development charges. Table 1 offers a simple approach to understanding where these funds reside. It aggregates single-tier, lower-tier and upper-tier municipalities into their associated upper-tiers to display Ontario’s top 10 holders of reserve funds. Table 1 includes per capita estimates to compare the extent of municipalities’ reserves and draws attention to the Regional Municipalities of York and Durham.

Although this paper does not analyze which portion of the accounts would best benefit from investment pooling, these reserves clearly represent a potentially significant resource for fund consolidation.

Several reasons exist for the growth of local government reserve funds. One key factor is the relationship between revenue collection and population. Figure 3 distinguishes between GTA and non-GTA jurisdictions. It shows how $24.5 billion – more than 60 percent of the total $39.7 billion in Ontario’s reserve funds – are concentrated in the GTA despite the region containing only 29 of Ontario’s 444 local governments. However, the concentration of these funds is not exclusively linked to the population. Instead, municipalities with high population growth rates see continual growth in reserve funds. One way to analyze the growth rate in local government regions is by examining the change in total private dwellings. Using this method, Figure 3 distinguishes municipalities by their housing growth rate, captured by evaluating the change in total private dwellings. Interestingly, Figure 3 shows that the Regional Municipalities of York and Halton had the very highest total private dwellings growth from 2009 through 2020.

However, the second-place set of municipalities grew between 12 percent and 16.9 percent and held the majority of reserve funds in Ontario. Combined, Dufferin, Durham, Lanark, Ottawa, Oxford, Peel, Prescott and Russell, Simcoe, Sudbury, Toronto, Waterloo and Wellington hold 51 percent of the municipal reserve funds in Ontario, amounting to $20.5 billion in 2020.

The Case for Pooling Municipalities’ Cash and Temporary Investments

There is a second way to think about municipal reserves and cash holdings. Ontario has 444 cities, districts, counties and regional municipalities. Each local government maintains a budget line for “cash and temporary investments,” a phrase referencing bank deposits and highly liquid securities that typically have short maturities.

Local governments’ need to support ongoing and unexpected expenses means they should work

to maximize returns while also having significant liquidity. Examining the extent of municipal cash and temporary investments in Ontario provides another avenue for considering the benefits associated with LGIPs.

Evaluating changes in municipal cash holdings from 2009 to 2020 is the first step toward assessing the potential benefits of pooling these assets. Ontario’s cities, districts, counties and regional municipalities submit annual financial statements about their cash and temporary investment holdings to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs. This section determined the extent of local governments’ cash holdings and temporary investments by replicating the method used to analyze reserve funds. The author examined Line 299 in Schedule 70 from publicly available financial statements released between 2009 and 2020.

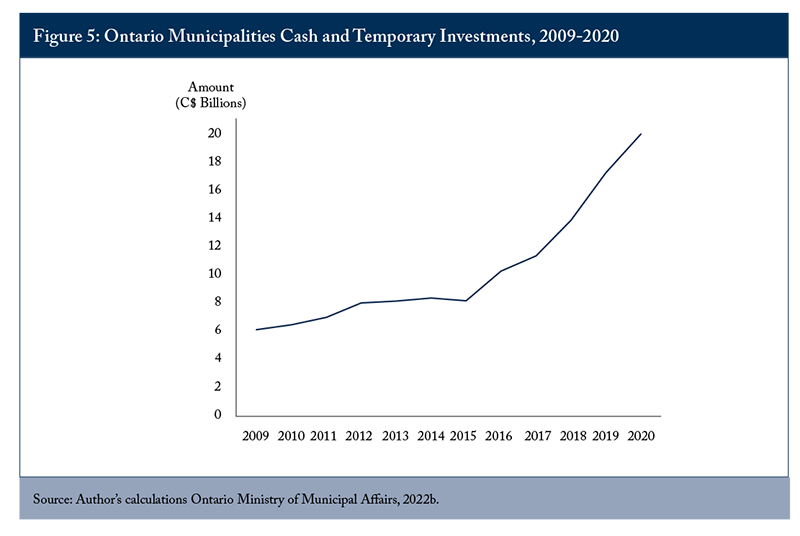

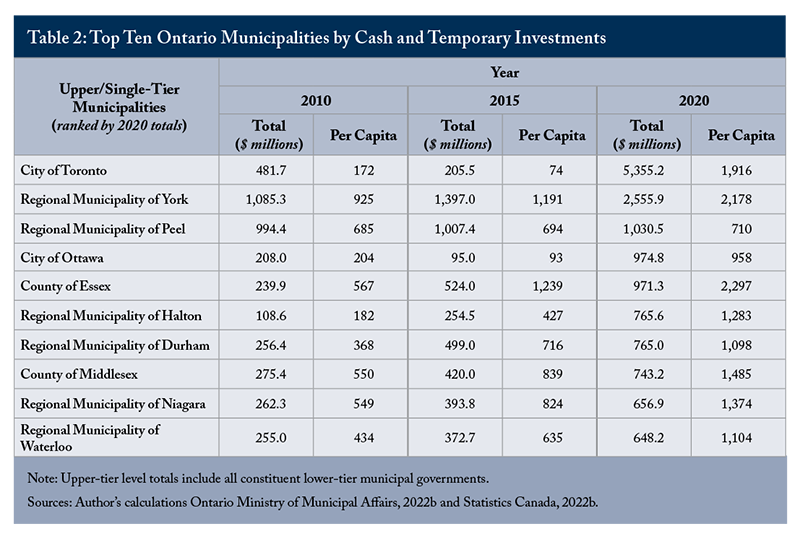

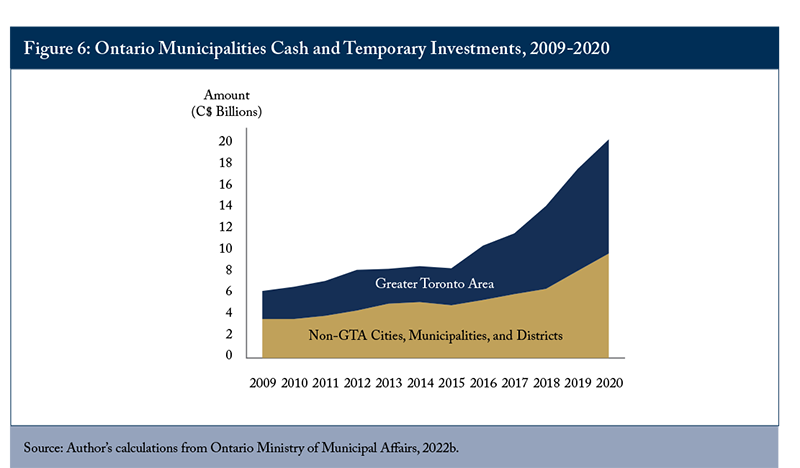

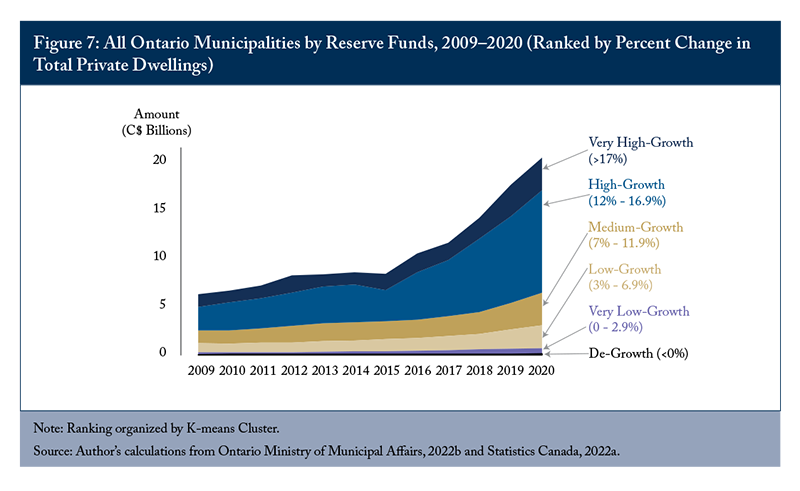

By 2020, Ontario’s local governments’ cash holdings and temporary investments reached $20.1 billion, growing 225 percent from $6.2 billion in 2009. While cash amounts generally grew annually, Figure 5 shows an increased cash-holdings growth rate after 2015. These amounts are particularly sizable for the top 10 holders of cash and temporary investments shown in Table 2. The table also includes per capita estimates to compare the extent of municipalities’ cash and temporary investments, highlighting the County of Essex and the Regional Municipality of York. These cash holdings and temporary investments offer another consideration for evaluating the benefits of consolidating public funds.

The key factors driving the growth of local government cash holdings are similar to those reported in the previous section. The increase is due to the relationship between revenue collection, population and municipal growth rates. The $20.1 billion in cash holdings and temporary investments are concentrated in the GTA or are linked to high-growth-rate municipalities. This concentration is one consideration for any move toward fund

pooling, as the City of Toronto Act would limit the amount of funds available for consolidation from the GTA. Figure 6 distinguishes between GTA and non-GTA jurisdictions. It shows how the GTA is home to more than half of these funds in Ontario – amounting to $10.5 billion – despite being home to only 29 of 444 local governments. Indeed, Figure 7 shows how nearly 52 percent of cash holdings, some $10.4 billion, are centred in municipalities with high growth rates as measured by changes in total private dwellings (i.e., Dufferin, Durham, Lanark, Ottawa, Oxford, Peel, Prescott and Russell, Simcoe, Sudbury, Toronto, Waterloo and Wellington).

Conclusions and Recommendations

Ontario’s growing municipal reserves and cash holdings raise questions about how best to manage and utilize these funds. Consolidating these funds as a local government investment pool can provide numerous benefits, including increased efficiency and more effective management of taxpayer dollars. For these reasons, this research brief has examined the case for consolidating public assets in Ontario. It identified some $39.7 billion in reserve funds held by local governments.

Any efforts to manage these funds must recognize that their growth corresponds to high population growth areas, particularly within the GTA. However, it is also essential to realize that the province’s Municipal Act limits investment durations for these monies to short-term, fully liquid investments. Therefore, this entire sum is not available in the sector for long-term investments.

Moves toward pooling and investing these funds require several steps, including clarifying and sharing legislative frameworks concerned with the potential pooling of reserve funds, carefully considering the cash flow needs of municipalities, ensuring the availability of investment products suitable to public agencies and establishing partnerships with key stakeholders.

First, there is a need for legislative clarity about what possibilities exist for fund consolidation and investment. Legislators may feel that these policies are sufficiently clear, but the lack of uptake by municipalities suggests that more communication may be needed. For instance, Sections 418 and 418.1 of the Ontario Municipal Act pertain to fund consolidation with a central investment manager. The associated regulations, 438/97: Eligible Investments, Related Financial Agreements and Prudent Investment, should be clarified, particularly with respect to development-charge reserve funds. Only a handful of Ontario municipalities have interpreted the prudent investor regime as enabling pooled investments. It is necessary to clarify who would be responsible for auditing disbursements to ensure compliance with provincial law and municipal bylaws in any proposal to pool municipal funds. Although development charges may be necessary in some cases, the goal should be to target their use while using associated investment returns to offset the continued growth of these charges.

Second, the financial staff of local governments has expert knowledge in fund management. While existing regulations define municipal investment thresholds, successful fund pooling depends on liaising with these workers, who can determine the percentage of reserve funds that could be invested. Financial staff will more clearly understand municipalities’ cash-flow needs. Conversations with the Municipal Finance Officers’ Association of Ontario would be helpful.

Third, investment managers must offer investment products suitable to local governments. ONE Investment provides various investment products, including money-market funds, fixed-income and equity portfolios, and high-interest savings accounts. However, it is unclear what other products are available from public investment managers, such as IMCO. These entities must communicate different investment options’ potential risks and returns to public agencies. Any move toward consolidating municipal funds is contingent on studying whether the benefits of better overall returns outweigh the costs of establishing disbursement mechanisms for accessing funds.

Fourth, a fruitful path toward fund consolidation requires a partnership among various stakeholders. In the case of local government funds, this collaboration should involve the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario, the Municipal Finance Officers’ Association of Ontario, the Investment Management Corporation of Ontario, ONE Investment, the Government Finance Officers Association, and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), among others.

Consolidation of public assets may result in enhanced efficiency and cost savings. However, it also raises concerns regarding the loss of local control and accountability, as well as the possible detrimental effects on local communities and stakeholders. When considering the case for consolidation, it is crucial to weigh the potential benefits and risks and evaluate Ontario’s policy context and changing political landscape. Any move toward pooling public funds in Ontario must consider these risks while appreciating the cash-flow demands of municipalities. Beginning with Ontario’s 2023 third-party review of development charges, future partnerships and analysis will help determine the best course of action for pooling Ontario’s municipal reserves and cash holdings.

1 These assets are held by the Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan (HOOPP), Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (OMERS), Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP), University Pension Plan (UPP), Ontario Pension Board (OPB), and the OPTrust.

2 Perhaps the world’s most comprehensive resource on municipal finance, Ontario’s Financial Information Return portal allows for a detailed breakdown of municipalities’ budgetary lines and schedule entries.

3 Given the lack of comprehensive and reliable data on the long-term investment horizons of the individual reserve funds, it is not feasible to determine which portion of the $39.7 billion would benefit from investment pooling.

4 These figures are rounded to the nearest million. According to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs Financial Information Return, Schedule 60, the specific 2020 figures amount to discretionary reserve funds ($15,447,291,287), obligatory reserve funds ($11,740,813,022) and other reserves ($12,552,538,940). To note, these reserve fund balances do not recognize the debt obligations that these funds support.

5 This figure is rounded to the nearest million. According to the Financial Information Return, Schedule 70, Ontario municipalities held $20,051,420,277 in cash and temporary investments in 2020.

6 According to their annual reports, IMCO had $79 billion in assets under management (AUM), ONE Investment had $2.9 billion in AUM, and Agricorp had $790 million in AUM as of December 31, 2021.

7 The investment return was calculated based on the Interest and Investment Income and Balance January 1, as outlined in Schedule 61.

8 Bill 23 comprised 10 schedules that modified various acts, including the City of Toronto Act (2006), Conservation Authorities Act, Municipal Act (2001), New Home Construction Licensing Act (2017), Ontario Heritage Act, Ontario Land Tribunal Act (2021), Ontario Underground Infrastructure Notification System Act (2012), Planning Act, and Supporting Growth and Housing in York and Durham Regions Act (2022). The Bill also made significant changes to the Development Charges Act (1997).

9 Specifically, Bill 23 – More Homes Built Faster Act, 2022 significantly changes the Ontario Development Charges Act, 1997.

10 Renovations are also subject to development charges when they result in the conversion of use or increased usability of buildings.

11 More specifically, development charges are directed toward capital works, municipal infrastructure, new public buildings, and the services provided for redevelopments and to residential and commercial properties in new areas.

12 The Financial Information Return portal does not provide enough information to explore the investment horizons of reserve funds.

13 Many municipalities define short-term maturities as financial instruments with maturities of three months or fewer from the date local governments acquired them.

References

Association of Municipalities Ontario [AMO]. 2022. “Province Responds to AMO Calls for Municipal Funding.” November 30. Available at:

https://www.amo.on.ca/advocacy/municipal-gov-finance/province-responds-amo-calls-municipal-funding

Beath, A., Betermier, S., Van Bragt, M., Spehner, Q. , and Liu, Y. 2022. “Green Urban Development: The Impact Investment Strategy of Canadian Pension Funds.” Global Risk Institute. Available at:

https://globalriskinstitute.org/publication/green-urban-development-the-impact-investment-strategy-of-canadian-pension-funds/

Bland, R. L., Nukpezah, J. A., and Shinkle, P. 2015. “Determinants of depositor demand for the Texas local government investment pool.” Public Budgeting & Finance, 35(3): 95-115. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/pbaf.12068

Bovaird, T. 2016. “The ins and outs of outsourcing and insourcing: what have we learnt from the past 30 years?” Public Money & Management, 36(1): 67-74. Available at:

https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.1093298

Carvalho, G. 2017. “Cities as Prudent Investors: New Rules for Investment by Ontario Municipalities.” NO 18 Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance.

Childs, M., and Authers, J. 2016. “Canada quietly treads radical path on pensions.” Financial Times. August 24. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/99075c68-68f9-11e6-a0b1-d87a9fea034f

Cook, T. Q., and Duffield, J. G. 1998. “Money market mutual funds and other short-term investment pools.” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Dachis, B. 2018. A Roadmap to Municipal Reform: Improving Life in Canadian Cities. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Davis, H., and Walker, B. 1997. “Trust-based relationships in local government contracting.” Public Money and Management, 17(4): 47-54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00091

Development Charges Act of 1997, S.0. Chapter 27. Available at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/97d27#BK3

Economist Magazine. 2012. “Maple revolutionaries.” May 3. Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2012/03/03/maple-revolutionaries

Found, A. 2019. “Development Charges in Ontario: Is Growth Paying for Growth?” Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance. Jan. 16.

Hayes Jr, V. R. 1999. “The dangers of relying on a legal list: a case study of the West Virginia Consolidated Investment Fund.” Public Budgeting & Finance, 19(4): 49-64.

Hochrainer, S., and Mechler, R. 2011. “Natural disaster risk in Asian megacities: A case for risk pooling?” Cities 28(1), 53-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2010.09.001

Kaufman, I. 2022. “City bets more investment risk will pay off.” TBnewswatch. Jan.25. Available at:

https://www.tbnewswatch.com/local-news/city-bets-more-investment-risk-will-pay-off-4991805

Kim, J. 2016. “Return of money or return on money? Analyzing asset concentration of local government investment pool portfolios.” Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management. March.

Lipshitz, C., and Walter, I. ‘Public pension reform and the 49th parallel: Lessons from Canada for the U.S.’ Financial Markets, Inst & Inst. 2020 (29): 121– 162. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/fmii.12133

Lynch, T. D., Shamsub, H., and Onwujuba, C. 2002. “A strategy to prevent losses in local government investment pools.” Public Budgeting & Finance 22(1): 60-79.

Markowitz, H. 1952. “Portfolio analysis.” Journal of Finance, 8: 77-91.

Maynard, D. E. 1989. “Gambling with public funds: State investment pools revisited.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 8(1): 101-103.

McCue, C. P. 2000. “The Risk‐Return Paradox in Local Government Investing.” Public Budgeting & Finance, 20(3): 80-101.

Modlin, S. 2016. “Getting All You Can: County Government Investment Pool Participation Based On Need or Want.” Public Administration Quarterly, 40 (4): 949-970.

Nukpezah, J. A. 2018. The effects of institutional typologies on the performance of state-sponsored local government investment pools. Public Money & Management, 38(3): 213-222.

____________. 2022. “Ethics and the Evolving Public Funds Investment Decision Effectiveness. Public Integrity, 1-12. April. Available at:

https://DOI: 10.1080/10999922.2022.2054573

Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs. 2022a. “Financial Information Return, Schedule 60: Continuity of Reserves and Reserve Funds (2009–2021)” [Data set]. https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/fir/index.php/en/by-schedule-and-year/year-2009-and-on/

____________. 2022b. “Financial Information Return, Schedule 70: Consolidated Statement of Financial Position (2009–2021)” [Data set]. Available at: https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/fir/index.php/en/by-schedule-and-year/year-2009-and-on/

____________. 2022c. “2022 Financial Information Return Instructions.” Available at: https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/fir/wp-content/uploads/fir-files/municipal-reporting/fir-instructions/2022/FIR2022%20Instructions1.pdf

Porter, K. 2022. “City of Ottawa hopes to boost investment returns with a new board.” CBC News. June 7. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/city-ottawa-prudent-investor-regime-1.6480379

Skerrett, K., Weststar, J., Archer, S., and Roberts, C. 2017. The Contradictions of Pension Fund Capitalism. Cornell University Press.

Statistics Canada. 2022a. “Table: 98-401-X2021002 Census Profile, 2021: Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations” [Data table]. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/subjects/population_and_demography/census_counts/dwelling_counts_and_types

____________. 2022b. “Table: 17-10-0139-01 Population estimates, July 1, by census division, 2016 boundaries, annual frequency” [Data table]. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710013901

The Canadian Press. 2022. “Ontario promises to make municipalities ‘whole’ if they can’t fund infrastructure due to new housing law.” CBC News. Nov 30. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-bill-23-reaction-1.6669428

Thompson, F. 1988. “Taking full advantage of state investment pools.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 7(2): 353-356.

Thompson, J. 2017. “Canada’s trailblazing pension reforms pay dividends.” Financial Times. Sept 24. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/5f2f05ec-97e5-11e7-b83c-9588e51488a0

Treasury Board Secretariat. 2022. Public Accounts of Ontario: Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements, 2021–2022. Treasury Board Secretariat Office of the President. Available at: https://files.ontario.ca/tbs-2021-22-annual-report-and-consolidated-financial-statements-en-2022-09-21.pdf