Shortcomings in Seniors' Care: How Canada Compares to its Peers and the Paths to Improvement

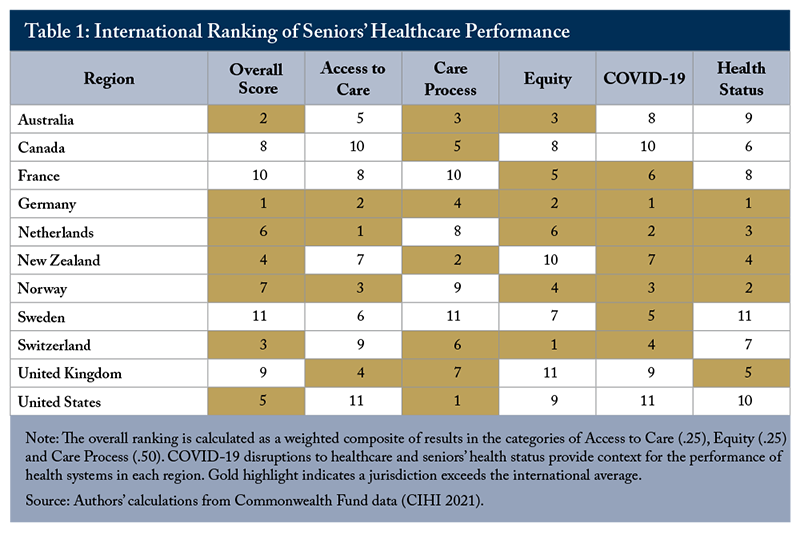

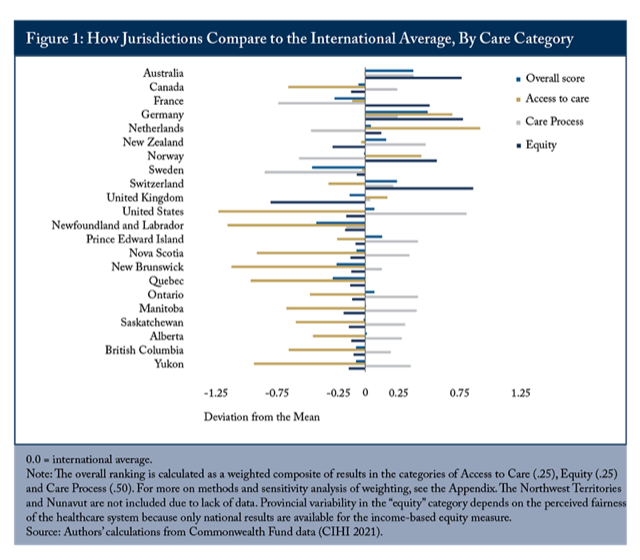

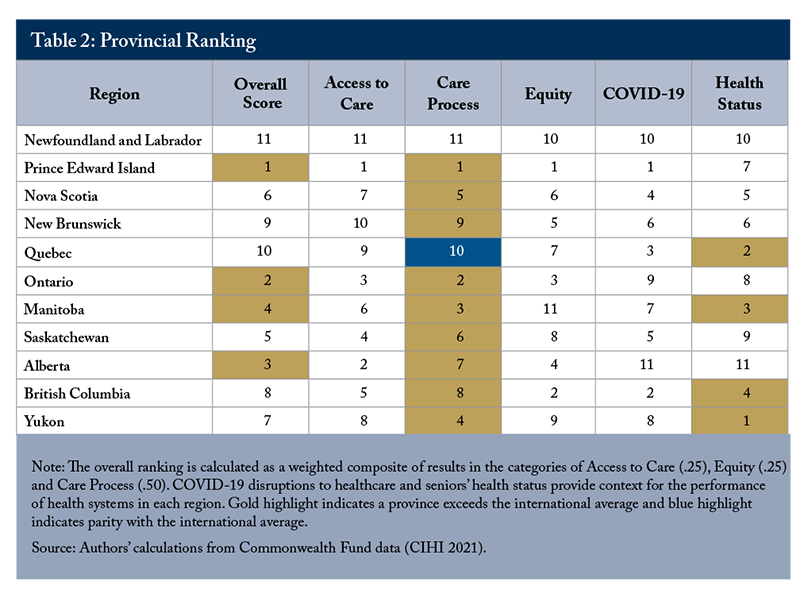

- Among 11 countries surveyed by the Commonwealth Fund, Canada’s seniors’ care ranks eighth, ahead only of France, the UK and Sweden. At the provincial level, some provinces compare more favourably to international jurisdictions while others, particularly Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec, sit at the bottom of the ranking. PEI, Ontario, Alberta and Manitoba, rank above the Commonwealth Fund international average overall, but no provinces achieve the international average on equity, based on race, for example, or access to care, based on affordability and timeliness.

Comparing provincial senior’s care to other jurisdictions reveals the magnitude of domestic shortcomings in care for seniors. Paths to improvement include better access to care and greater equity, where Canada ranks second last.

Comparing provincial senior’s care to other jurisdictions reveals the magnitude of domestic shortcomings in care for seniors. Paths to improvement include better access to care and greater equity, where Canada ranks second last.

The authors thank Parisa Mahboubi, Charles DeLand, Mawakina Bafale, Janet Davidson, Michael Gardam, Mike Hamilton, David Walker, and Jennifer Zelmer for comments on an earlier draft. The authors retain responsibility for any errors and the views expressed.

Introduction

Benchmarking Canada’s healthcare systems to those in comparable wealthy nations can provide insights into its relative performance and inform priorities for improvement. An international survey carried out by the Commonwealth Fund, a US-based foundation dedicated to improving healthcare systems, provides data for this comparison. The Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults (CMWF) focused on a random sample of seniors aged 65 and older in 11 countries and asked about their experiences, interactions and perceptions of the healthcare system and health providers. The survey covers different aspects of seniors’ care including primary and specialist care, chronic illness care, coordination of care, hospital care, home care, end-of-life care planning, the health of seniors, and their overall perceptions of the health system. The 2021 survey also provides information about how the COVID-19 pandemic affected seniors and their experience with the healthcare system.

Using 49 indicators from the CMWF survey, we created five summary categories: access to care, care process, equity, the impact of COVID-19 on seniors, and the health status of seniors in Canada compared to peer countries.

Overall, Canada ranks 8th out of 11 countries included in the survey. Comparing the results shows some provinces such as Prince Edward Island and Ontario are strong performers in areas like care process, which includes factors such as coordination across providers and patient engagement. Other provinces, notably Newfoundland and Labrador, have severe issues, often ranking close to last in areas like access to care and equity.

In order to improve Canada’s international standing in seniors’ care, some fundamental policy and organizational issues need to be addressed. While Canada generally performs well in the care process category, it performs poorly in terms of access to care and equity, with no provinces reaching the international average in either category. Addressing access challenges for seniors through improved continuity of care, affordability and reducing wait times would improve Canada’s rank. The variations in domestic results and international comparisons offer good lessons for each province.

Overall Score

The top-performing countries overall are Germany, Australia, and Switzerland (Table 1, Figure 1).

Canada’s seniors’ care performs poorly compared to its peer countries. It is below the international average due to poor access to care and equity, but meets the international average for care processes. Among 10 provinces and one territory with survey results, Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec are the major drags on performance, ranking below most comparator jurisdictions (Figure 1).

Related research suggests that Canada’s relative performance on seniors’ care is slightly better than its performance in total population healthcare, though still ranking below the international average. An international comparison by the Commonwealth Fund using survey responses from physicians, adults and seniors ranked Canada 10th out of 11 countries (Schnieder 2021) in total population healthcare.

Similarly, analysis of previous rounds of those surveys showed Canada as 9th out of 11 countries, ahead of France and the US (Busby, Muthukumaran and Jacobs 2018). Notably, in almost all the combined analyses of Commonwealth Fund surveys, the US is invariably a poor performer overall, but ranks above average in the care process domain. Our results show a similar trend – the US ranks first in care process, but at or near the bottom of the rankings for access and equity. However, the US compares slightly more favourably to other nations on seniors’ care than it does on overall popuation healthcare.

Insights from the International Comparison

Every country has a different mix of policies, services and funding mechanisms that influence the functioning and results of their healthcare systems. Each country has a limit to what can be spent on healthcare and might choose different strategies to try to optimize outcomes. By surveying populations about their perceptions and experiences with the healthcare system, we can compare results across different systems. There are, however, important limitations to the types of analysis that can be performed and the conclusions that can be drawn from international survey data.

The CMWF survey offers unique and detailed data on the experiences of patients; it does not, however, capture administrative or financial information that would allow for more direct comparative analysis of policies. The Commonwealth Fund survey cannot draw conclusions about the relative efficiency or resulting clinical outcomes of specific policies in other jurisdictions. Some experts call for caution about the limits of ranking exercises because they do not specifically adjust for different demographic and socioeconomic circumstances in each province (Hewitt and Wolfson 2015). It does, however, provide a broad comparable overview of the populations’ perceptions and interactions with healthcare systems and providers. It can also highlight priority areas for improvement, or common challenges across jurisdictions and allows for comparison across many aspects of care. Our analysis shows that Canada does quite well on care processes, but the senior population faces challenges accessing healthcare services due to costs, wait times and the availability of care, relative to other countries.

Overall, Canada ranks among the top half of comparator countries in the Care Process category, but is below average in the categories of access to care and equity (Table 1). Germany is the only country to rank above the international average in all categories and also the only country to outrank Canada in every category including COVID-19 impact and health status. Germany and the Netherlands rank first in access to care and Switzerland, Germany and Australia perform the best in the equity category.

An international comparison suggests that top-performing countries such as Germany and the Netherlands rely on the following features to attain better and more equitable health outcomes:

1. They provide universal coverage and remove cost barriers so seniors can get care when they need it. This full coverage includes highly beneficial preventive services, primary care, and effective treatments for chronic conditions. For example, in the Netherlands, primary care physicians are “obligated to provide at least 50 hours of after-hours care (between 5:00 pm and 8:00 am) annually in order to maintain their professional licensure” (Schneider et al 2021).

2. They invest in primary care systems to ensure that high-value services are equitably available locally in all communities to all people, reducing discrimination and inequity.

3. They invest in home care and encourage seniors to live independently for as long as possible. Community nurses encourage and train seniors’ relatives and family to get involved in their care, and provide preventative and curative care at the same time. The municipal level of care also empowers seniors and gives them freedom, autonomy, and wellness.

Insights from the Provincial Comparison

PEI,

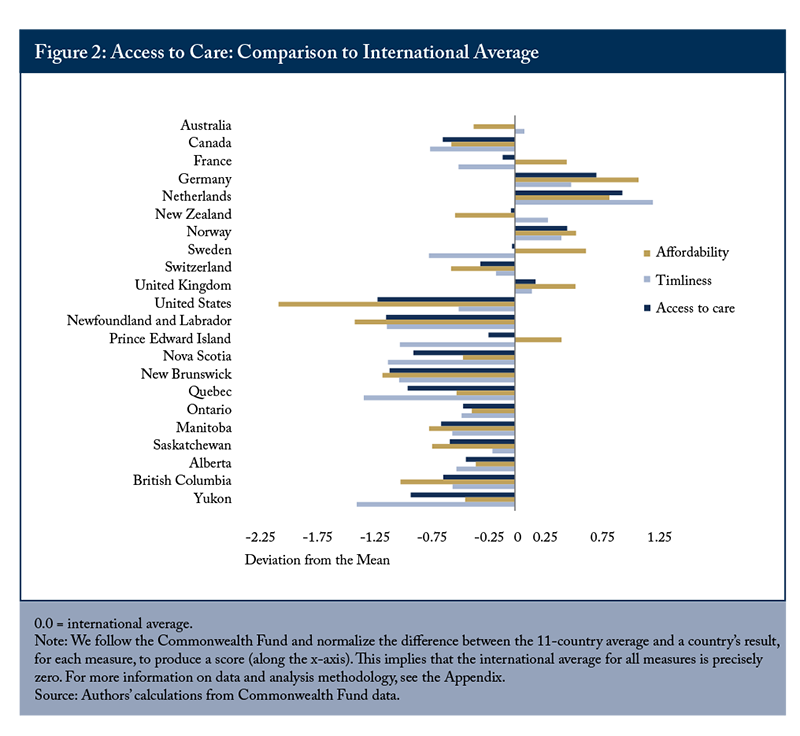

Access to Care: Challenging in Canada

Access to care includes measures of senior care’s affordability

In terms of affordability, only PEI is slightly above the international average in this sub-category. Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan rank below all comparator countries except the US in terms of affordability of healthcare for seniors. Senior patients across the country cited cost as a major reason for skipping treatment and prescriptions and avoiding medical care or dental care. Four percent of seniors surveyed in Canada say they did not fill a medication, skipped doses, skipped tests or treatments, or didn’t see a doctor when they had a medical problem due to cost.

Timely access to care is also a challenge across the country, with all provinces ranking below the international average. Saskatchewan and Ontario scored the highest among provinces on this measure, while the Yukon, Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec rank the lowest among all comparator regions.

Canada is below the international average for obtaining after-hours care and same- or next-day appointments for those who need them. Only 31 percent of Canadian seniors reported they could see a doctor or nurse either the same day or the next day, compared with 79 percent in Germany and 70 percent in the Netherlands. However, during the pandemic, Canada’s health system expanded virtual care delivery, improving access to primary care during disruptions to in-person visits. Among international peers, Canada stands out in this indicator with more seniors in Canada (71 percent) reporting having had virtual appointments compared with their international peers (39 percent).

Equity: Persistent Challenges

The CMWF survey and associated reports also measure equity and include questions about level of income, difficulty paying for medical procedures, and perceived fairness of the healthcare system. Unfortunately, the data linking income levels to responses related to access and affordability are not publicly available for individual provinces and we rely on perceived equity to compare performance across jurisdictions.

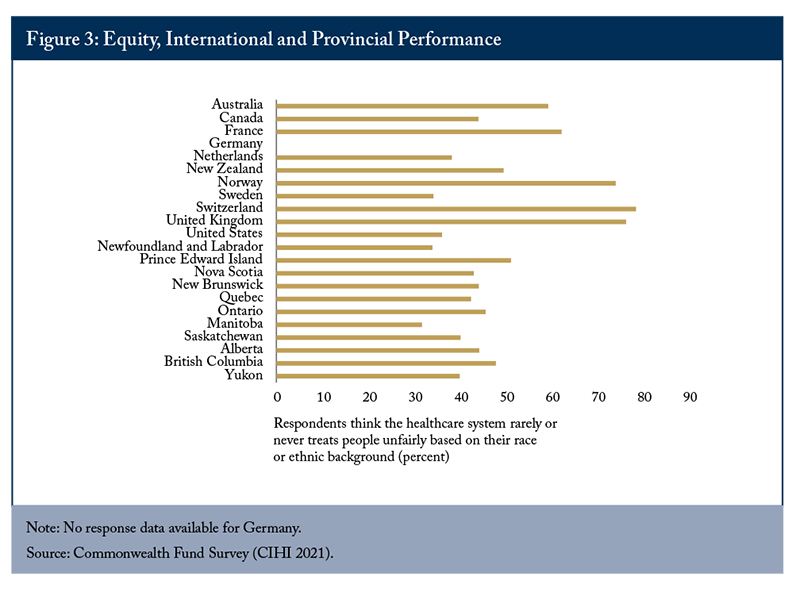

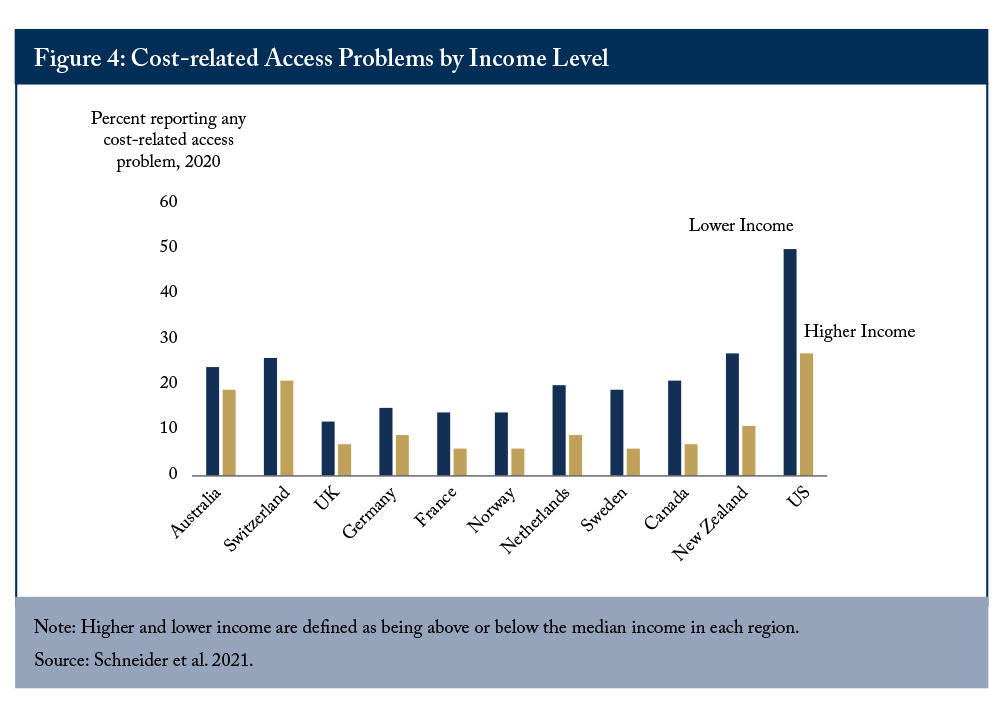

On that score, Manitoba places last with only 32 percent of seniors thinking that people are rarely or never treated unfairly based on race or ethnic background. Sweden and Newfoundland and Labrador tied in second last place, with only 34 percent (Figure 3) thinking so. Switzerland has the highest perceived fairness at 79 percent. PEI and Ontario have the highest perceived fairness within Canada. This measure mirrors the rather dismal results reported by the more comprehensive international comparison measure where Canada ranks second last (ahead of the US). Similarly, in the international ranking, Canada ranks below the international average in terms of the gap between proportions of high and low income people reporting cost-related problems accessing the healthcare system (Figure 4).

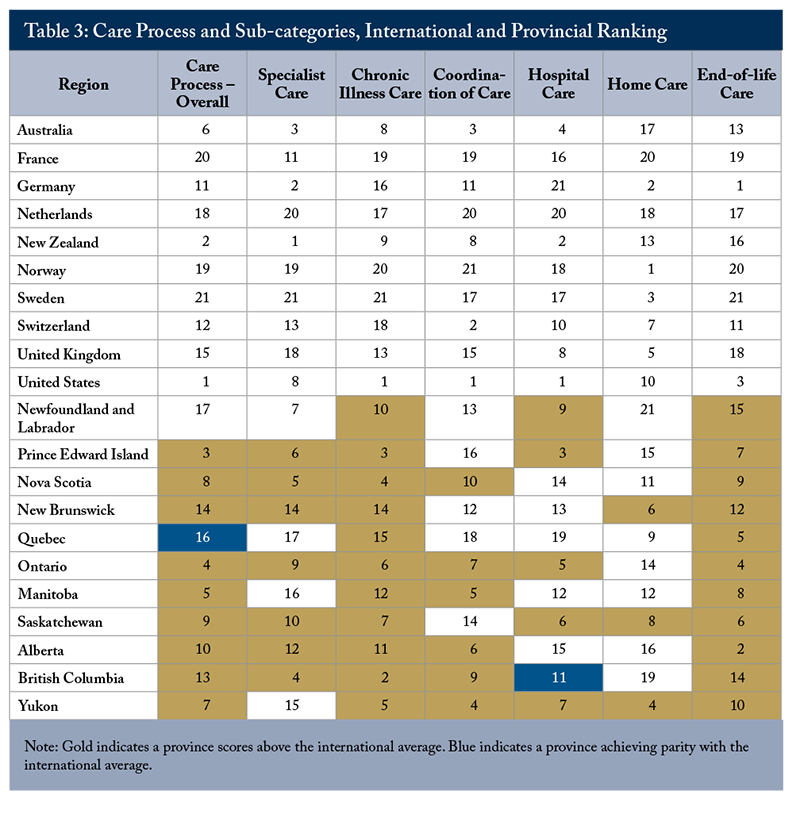

Care process is a composite measure including responses to questions covering aspects of quality, safety and continuity across the health care system including preventative care, safe care, care coordination between providers, patient engagement and preferences. The US, which ranks last on access to care and equity, ranks highest on care process and the sub-domains of chronic illness care, coordination of care and hospital care. Canada and most provinces are above the international average (Table 3).

Interestingly, Germany ranks near the top of the list on overall scores and for equity and access to care but shows some weakness on care process in particular sub-domains. Notably, it remains above the international average on most measures, especially home and end-of-life care, but has below average performance in coordination of care and ranks at the bottom for hospital care.

Investigating the sub-category scores shows some common successes for Canadian provinces: all provinces rank above the international average on chronic illness care and end-of-life care planning. More Canadian seniors reported feeling confident about their ability to control and manage their health problems, compared to their international peers. They are also among the most likely to have a treatment plan that they can carry out in their daily life. In British Columbia and Prince Edward Island, the best performing provinces in this sub-category, chronically ill patients reported good communication with health professionals in regard to treatment options. Canada performs quite well on end-of-life care, ranking third. Most of the provinces also perform strongly, with Alberta and Ontario leading the way.

Compared to seniors in other countries, more Canadian seniors engaged in end-of-life care planning.

There are also common challenges related to care process across the country. Most provinces score below the international average for home care and half are below average in terms of coordination of care. Newfoundland and Labrador ranks last among provinces for home care, with 5 percent of the senior population receiving help from an aide, nurse, or other health professional, compared with an average of 29 percent in other provinces.

The sub-categories also show individual areas of improvement for particular provinces. For example, BC and Ontario score at-or-above the international average in all sub-categories except home care suggesting that improving access should be a priority area for improvement for seniors’ care. Specifically, a lower proportion of the population receives care from aides, nurses or other health professionals in British Columbia than elsewhere in the country. In Ontario, the proportion of adults over 65 years of age receiving such care is comparable to other provinces, but below the international average. Similarly, Saskatchewan scores above average in all sub-categories except for coordination of care. The Yukon could improve seniors care by improving access to specialists and its rank on this sub-category exhibits the chronic challenge for the territories of attracting and retaining specialist physicians to meet the needs of the population. In other provinces, the challenges in providing high-quality seniors care are more generalized. This is particularly evident with the lowest ranked provinces of Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador, which score below average in at least half of the sub-categories.

While there are some areas for improvement in care process, particularly home and community care, Canadian provinces generally perform well compared to international peers on the provision of seniors’ care.

COVID-19 Impact: Below Average

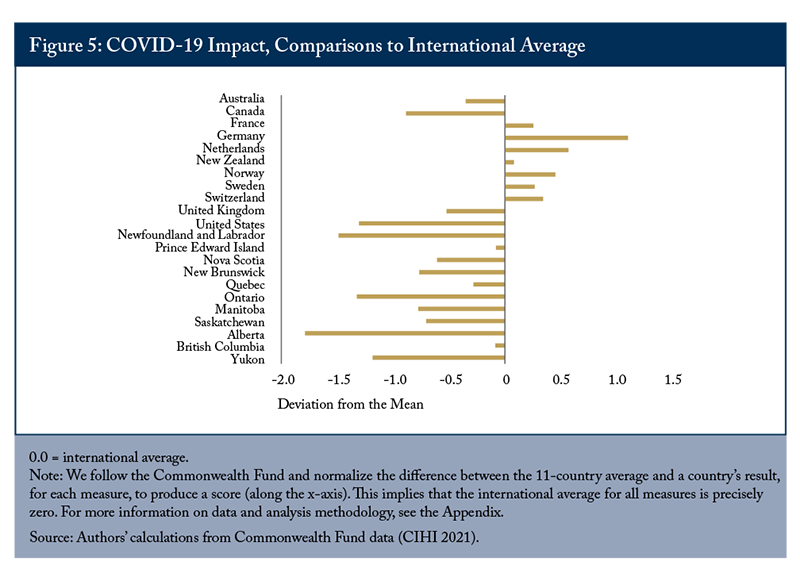

During the pandemic, Canada introduced restrictive public health measures to combat the spread of the virus, as did most other countries. The CMWF survey asked seniors about their vaccination status, disruptions to medical appointments and home assistance, and loss of income or employment. Aside from the United States, Canada performed the worst in terms of how COVID impacted its seniors and their experience with the health systems (Figure 5). However, Canada and all provinces did achieve higher vaccination rates in the senior population than the international average at the time of the survey.

Canadian seniors are more likely to report appointments with doctors being cancelled or postponed and that they used up all or most of their savings due to the COVID-19 pandemic than seniors in other countries (except the US). Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Ontario scored worst amongst provinces and score below the US. More than a third of seniors in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador had appointments with doctors or other health professionals cancelled or postponed due to the pandemic.

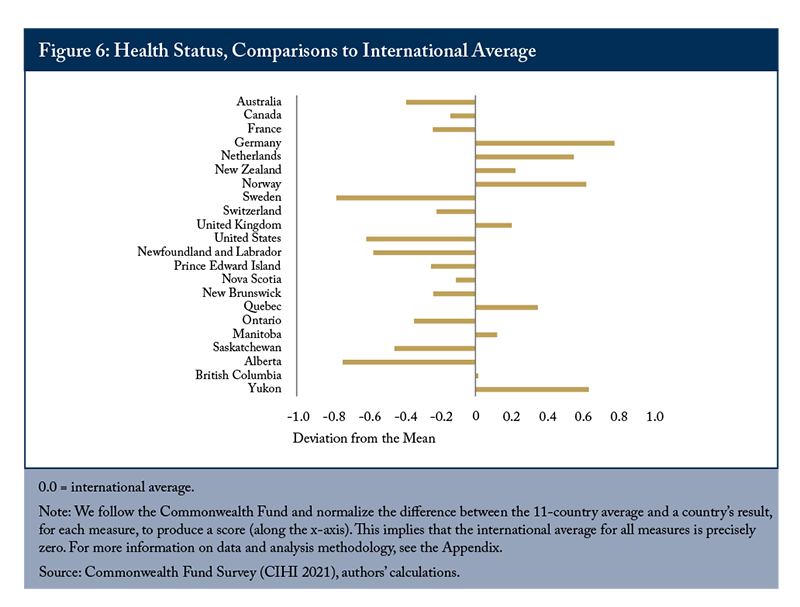

The overall health of seniors in the population has implications for their quality of life and need to access healthcare. If the senior population is very healthy, it is less challenging to provide high-quality, accessible and affordable health services, due to lower overall demand levels. The CMWF survey contains a number of questions related to seniors’ physical and mental health, as well as financial concerns. Comparing results across countries shows that seniors in Germany, Norway and the Netherlands have fewer chronic conditions, higher general health status and fewer financial concerns than in other jurisdictions. In Canada, seniors are more likely to have at least one chronic condition, take prescriptions drugs, or have experienced emotional distress than the international average. However, Canada is above average in terms of fewer seniors needing assistance with activities of daily living, or having financial concerns.

Across provinces, there is significant variability in the health status of seniors (Figure 6). New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, BC and the Yukon exceed the international average. Alberta’s seniors have the second lowest health status of all the comparator jurisdictions.

Impactful Improvements for Provincial Health Policy

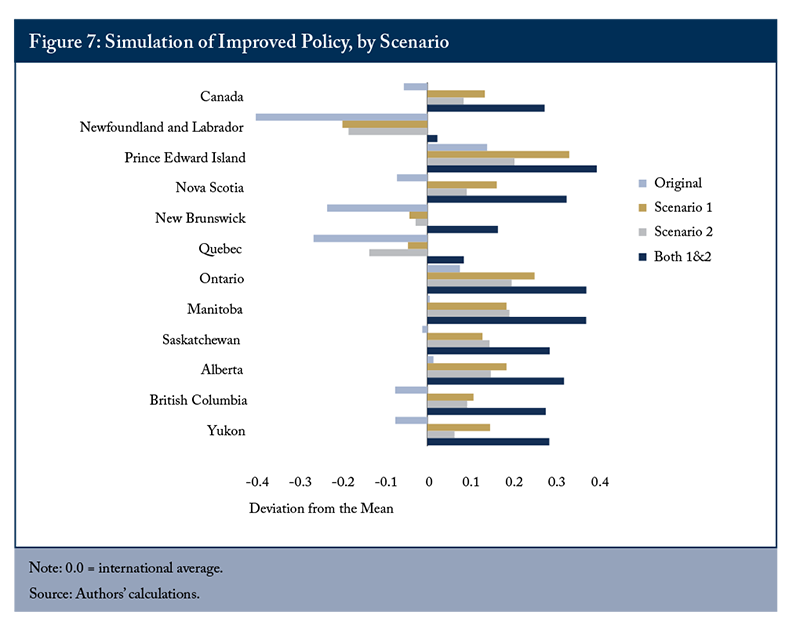

To evaluate how Canadian provinces could improve their standing in the international ranking, we simulate a number of scenarios where provinces meet the highest international standard for various survey questions. Since access to care is a common challenge across the country, we focus on this category as the highest priority for improvement.

Scenario 1: Improving access and timeliness, measured by:

• having a regular place or provider of care;

• availability of same or next day appointments; and

• difficulty in accessing after-hours care.

Scenario 2: Reducing Cost Barriers to Access, measured by:

• reducing the proportion of older adults who did not fill prescriptions, visit a dentist, or receive home care due to cost.

If Canadian provinces were able to achieve the highest international standard by improving access and timeliness to medical appointments or by reducing cost barriers to pharmaceutical, dental and home care, Canada would rank above the international average, or 5th out of 11. Achieving both outcomes would place Canada 3rd in the ranking. Similarly, in most provinces, achieving either goal would put performance above the international average (Figure 7). In Quebec, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador both goals would need to be achieved to exceed the international average.

Specifically, the improving access scenario includes the following goals: having 100 percent of older adults with a regular healthcare provider or a regular place they receive care (like New Zealand); having 79 percent of respondents saying they can get an appointment with a nurse or doctor the same or next day (like Germany); and having only 16 percent of the population have difficulty getting after-hours care (like the Netherlands). Reaching the goals of reducing cost barriers would mean having only 1 percent of older adults skipping doses of medicine or not filling prescriptions (like Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand and the United Kingdom), 2 percent avoiding the dentist (like Germany and the Netherlands) and 3 percent going without home care due to costs (like Germany and Sweden).

While these might seem like ambitious goals, some are within reach and others will take more time, investment and policy change to address. For example, 96 percent of older adults have a regular place or provider of healthcare; achieving the highest international standard would require matching 4 percent of older adults with primary care or designating a place for those without a provider to receive care (about 293,000 people). This target is ambitious, but is not impossible and the importance of primary care in managing ongoing healthcare needs as people age should make it a priority. Reducing the difficulty of accessing after-hours care from 59 to 16 percent, similar to the Netherlands, could be informed by that country’s approach. Primary care physicians there are “obligated to provide at least 50 hours of after-hours care (between 5:00 pm and 8:00 am) annually in order to maintain their professional licensure” (Schneider et al 2021).

Benchmarking the performance of Canada’s healthcare system against international peers shows our relative performance, priority areas for improvement and provides the international examples that can inform domestic policy and healthcare delivery changes.

Conclusion

International comparisons allow the public, policymakers, and healthcare leaders to benchmark Canadian and provincial performance against international peers and inform alternative approaches to delivering senior care. The current Canadian health system requires a fundamental change to ensure that policies, care pathways, incentive mechanisms, and funding align with the preferences and care needs of Canadian seniors (Wyonch 2021, Quinn Isenberg and Downar 2021, Drummond, Sinclair and Bergen 2020).

As the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, no nation has the perfect health system. By learning from what has worked and what hasn’t elsewhere in the world, Canada has the opportunity to learn from the best policies and practices that may move it closer to the ideal of a health system that achieves optimal health for all its seniors at an affordable price.

Appendix – Data and Methodology

The Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults randomly sampled the population age 65 and older in 11 countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States (there was an expanded sample of U.S. adults, age 60 and older, but the 60–64 age group is excluded from the data tables).

In Canada, a random digit dial sampling frame landline telephone design was used to obtain all completed interviews. The Canadian survey was conducted from March 13, 2021, to June 14, 2021, by Social Science Research Solutions in partnership with Léger. A minimum of 250 interviews were completed in each province, with 1,000 interviews completed in Quebec and 1,302 in Ontario. Yukon had 144 completed interviews and efforts were made to maximize completed interviews in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut given their relatively small population age 65 and older. In total, 4,484 interviews were completed across Canada. The overall response rate in Canada was 22.3 percent. The random sample of adults over 65 years of age represents about 0.06 percent of the senior population in Canada and includes very few responses from residents of long-term care homes.

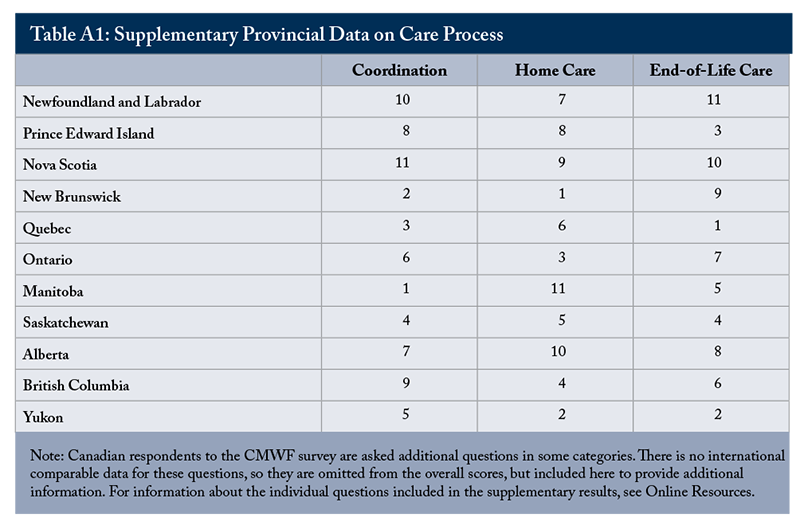

There are a total of 68 questions in the survey and we selected 49 of them as indicators for our analysis. Survey responses were reweighed if more than 5 percent of respondents indicated “unsure or uncertain” to the question. An additional seven questions are included in the provincial supplementary analysis (Table A1, below), but cannot be included in the overall results due to a lack of comparable international data. Similar to the Commonwealth Fund’s analysis, for each indicator we convert each country’s result to a normalized performance score. The indicator scores within each category are summed and re-scaled to a normalized category score.

We calculated performance differences as the standard deviation from average performance – a measure of the degree of difference between countries given the range of variation in this set of countries. Scores above zero indicate a region performs above the 11-country average while scores below zero indicate below-international-average performance.

For more information about the data and its limitations for analysis, see Schneider et al (2021) and CIHI (2022). For more information about the survey questions included in each category, see the online resources.

Supplementary Results

Sensitivity Analysis

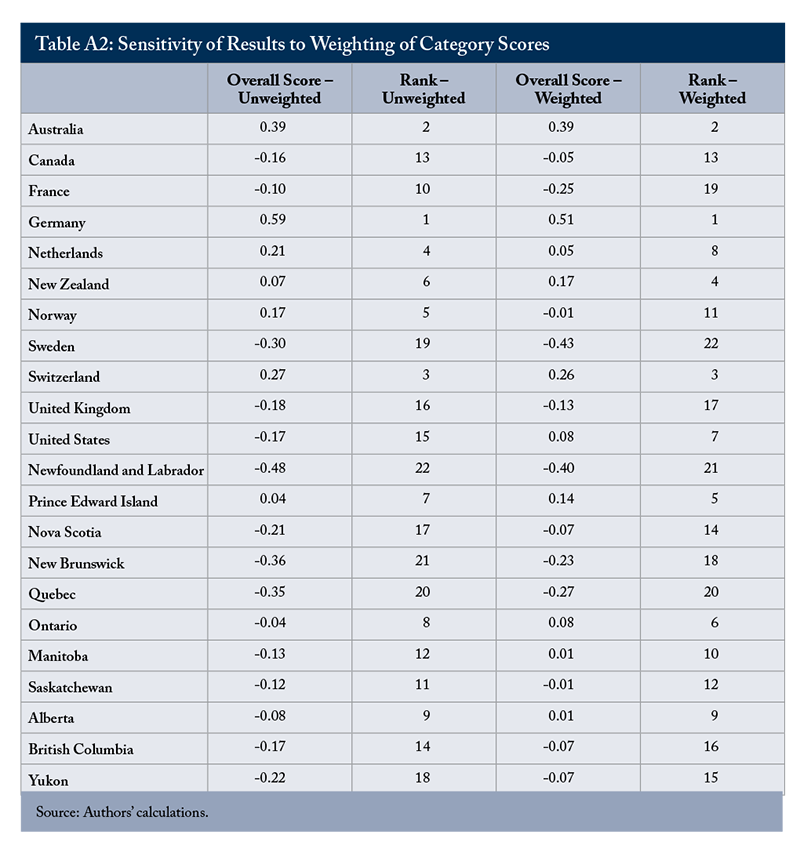

The overall ranking is calculated as a weighted composite of results in the categories of Access to Care (.25), Equity (.25) and Care Process (.50). Since the Care Process category contains the most questions and is more directly focussed on contacts with the healthcare system and the coordination between providers, we chose to give it a higher weight in the overall score. The rationale is to create a measure that is half directed to ability to access care and half to care delivery for those that do access the system. To evaluate the effect this choice has on the overall ranking, we include the unweighted scores and ranking below in Table A2. Putting more weight on Care Process has an effect on the numerical score for each jurisdiction, but only minimal change to the ordinal ranking. Jurisdictions that rank in the top third and bottom third on the unweighted ranking remain in those positions with the weighted overall scores (with the exception of France and the United States).

Appendix

This E-Brief is a publication of the C.D. Howe Institute.

Rosalie Wyonch is Senior Policy Analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute.

Tingting Zhang is Junior Policy Analyst at the C.D. Howe Institute.

This E-Brief is available at www.cdhowe.org.

Permission is granted to reprint this text if the content is not altered and proper attribution is provided.

The views expressed here are those of author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

References

Busby, C., R. Muthkumaran, and A. Jacobs. 2018. “Reality Bites: How Canada’s Healthcare System Compares to its International Peers.” Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute. Available at: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Final%20for%20release%20e-brief_271_Online.pdf

Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI). 2021. “Commonwealth Fund Survey, 2021.” Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/commonwealth-fund-survey-2021

Canadian Institute for Health Information. “How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2021 International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults in 11 Countries – Methodology Notes.” Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2022.

Drummond, D., D. Sinclair, and R. Bergen. 2020. “Aging Well.” Available at: https://www.queensu.ca/sps/sites/spswww/files/uploaded_files/publications/1%20Ageing%20Well%20Report%20-%20November%202020.pdf

Quinn, K., S. Isenberg., and J. Downar. 2021. “Expensive Endings: Reining In the High Cost of End-of-Life Care in Canada.” Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.

Schneider, Eric C., Arnav Shah, Michelle M. Doty, Roosa Tikkanen, Katharine Fields, and Reginald D. Williams II. 2021. Mirror, Mirror 2021 Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries. The Commonwealth Fund.

Wyonch, Rosalie. 2021. Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure: Seniors’ Care After COVID-19. Commentary 614. Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute.