From: Tammy Schirle

To: Canadians concerned about gender equity

Date: March 7, 2023

Re: The Surprisingly Smaller Gender Wage Gap

The gender wage gap in the private sector has remained smaller after 2019. In many ways this is surprising and could represent a good-news story for International Women’s Day tomorrow.

Why surprising? When we saw a narrowing of the gender wage gap between 2019 and 2020, there was good reason to say this was not a good-news-story. The reduced gap between men’s and women’s average hourly wage was concerning as it largely represented the well-documented fact that job losses in early months of the pandemic were unevenly distributed across the labour market. COVID-19 job losses hit hardest the workers with the least bargaining power – women, young people, and those with the lowest wages. As a result, women’s wages rose in the overall 2020 average only because the lowest-wage workers were taken out of the mix.

Meanwhile, women’s employment rates have more than recovered from 2020. In 2022, the employment rate of women aged 25-54 was 81.4 percent, 1.4 percentage points higher than in 2019. The rate at which these women are working full time is also higher. With this return to work after 2020, we might have expected a return of the higher gender hourly wage gap.

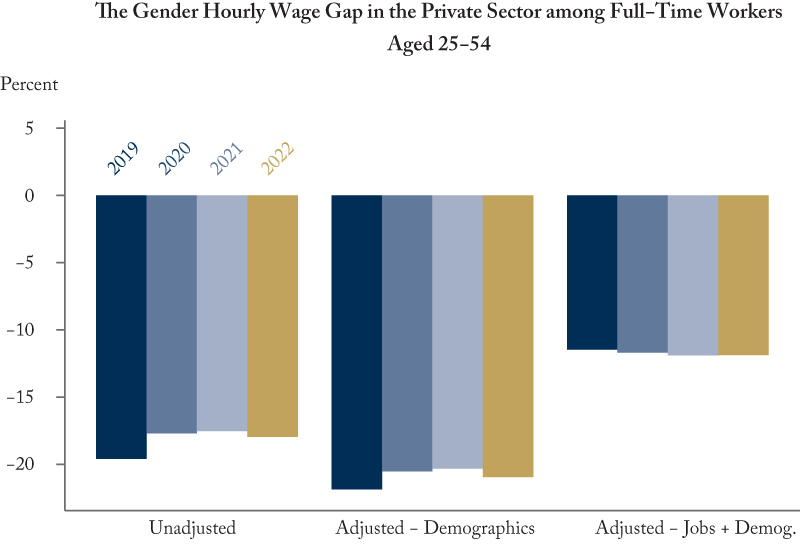

However, the gender gap remains narrowed. In 2022, women’s average hourly wages were roughly 18 percent less than men’s, smaller than 19.5 percent in 2019.

So what might explain this? As women have returned to work, it appears they have returned to different and potentially better jobs. Fewer women are now working in sales and service occupations, and fewer are in retail trade or accommodations and food services industries. Instead, they are now more likely to work in professional or technical occupations, in industries such as finance and insurance, or professional, scientific and technical services. The women appearing in full-time jobs also appear more educated than before the pandemic, with more women having post-secondary diplomas or university degrees.

That women are finding better job opportunities is clearly a good-news story.

However, it still comes with a note of caution. An important part of any wage gap analysis involves a more apples-to-apples comparison between men’s and women’s wages. The adjusted gender wage gap – whereby we account for gender differences in job characteristics and demographics that can help explain average wage differences – did not narrow after 2019 and appears to be increasing ever so slightly. This is potentially bad news and worthy of more research.

Going forward, it will be interesting to see whether this sectoral shift in female employment away from the low-wage service sector will last. As private sector employers facing a tight labour market struggle to find low-wage workers in the service sector, they could offer higher wages to encourage workers’ return and retention. This would clearly be good news for women working in these sectors. However, policy efforts to ease wage pressures for business – such as easing access to temporary foreign workers – would counteract this.

Tammy Schirle is a Professor of Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University, and is a C.D. Howe Institute Research Fellow.

To send a comment or leave feedback, email us at blog@cdhowe.org.

The views expressed here are those of the author. The C.D. Howe Institute does not take corporate positions on policy matters.

Negative values reflect the extent to which women’s hourly wage are less than men’s, using a regression framework as in Sogaolu and Schirle (2020). Adjusting for demographics accounts for gender differences in education, age, marital status, the presence of young children at home, and province. Adjusting for job characteristics includes union coverage, tenure, industry, and occupation. Source: Author’s calculations using the Labour Force Survey public use files.